The New Cult Canon: 'Speed Racer'

In 2008, I gave The Wachowskis' super-charged eyeball-stabber a "C." I wasn't yet ready for the future.

“I go to the races to watch you make art. And it’s beautiful and inspiring and everything art should be.” —Susan Sarandon, Speed Racer

“The Wachowskis may be guilty of being too far ahead of the curve: Maybe children one or two generations down the road will be able to process 135 minute of manic, kitschy inanity, but for now, it goes down in one big, indigestible lump.” — My original review of Speed Racer

No one ever likes to admit they’re wrong, but critics are a particularly stubborn bunch, because their opinions have already been rendered in public, etched into the digital firmament. I’ve written well over a thousand reviews in my career, and while I’m confident that my opinions in the vast majority of them are more or less unchanged, some objects have inevitably shifted during flight. One way to avoid the humbling act of revision is never to see films you suspect you’d gotten wrong, but the cult of the Wachowskis’ Speed Racer has gotten bigger and louder over the years since its 2008 release, and if I was going to bring back The New Cult Canon, I was going to have to contend with the “C” I slapped on it.

Was I wrong? Yes. Why did I recoil from this super-charged, iconoclastic, candy-colored blitz on the senses? Let me explain.

You can see in the review that I could recognize what the Wachowskis were attempting with their aggressive deployment of visual effects, which I called “borderline-experimental in the way it challenges the limits of perception.” I also called it “forward-thinking” and “visionary” before declaring it “much of the time unwatchable.” At the time—and even to a large degree today—I had an instinctual resistance to the growing plasticity of the medium, the way CGI and hyper-aggressive editing techniques had given films a weightlessness and, in action sequences, an absence of stakes, replacing the nuts-and-bolts of traditional filmmaking craft with a digital battering of the senses.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

The Wachowskis were easy enough to place in the same trend basket with lesser practitioners of the form like Michael Bay, whose first Transformers movie had tossed the old rules of filmmaking out the window. (Kent Jones had already identified Bay’s revolutionary ways as early as the July-August issue of Film Comment, in a much-discussed essay called “Bay Watch.”) They had limped away from The Matrix trilogy with The Matrix Revolutions, and Speed Racer seemed like a peculiar attempt to mine Japanese anime as a highly caffeinated, live-action family entertainment. That’s not exactly what happened—the film is much odder, more personal, and more adult-oriented in theme than expected—but I was not the only critic who perceived it as a sop to pre-adolescent boys, and rejected its assaultive visuals. Slate’s Dana Stevens described the experience eloquently:

Shapes hurtle toward you, then recede abruptly, each bearing some fragment of narrative information that has now passed you by forever. Nausea and anxiety begin to wash over you in overlapping waves.

But that’s the thing about cutting-edge work: Not everyone is ready for the future, even if they suspect they’re seeing it. Over time, Speed Racer has no longer seemed like a “big, indigestible lump” because my metabolism for processing images has changed, and its hummingbird flutter of montages, superimpositions, and visual effects is more legible. 13 years later, the film still stabs the eyeballs like a serial murderer, with its pixie-stick energy and a color scheme that deliberately clashes, as if a prankster swapped paint cans on Pedro Almodóvar’s production designer. Preparing to revisit Speed Racer, I feared those 135 minutes might again prove completely enervating—I tend to fall asleep during Bay’s Transformers films, like an overloaded computer shutting down. But the Wachowskis are not merely throwing images at the wall here. Once you adjust to the film’s pace, it’s easier to appreciate its craft.

That craft asserts itself in dazzling form in the opening reel, which zips around multiple timelines and planes of action to set up the tragedy and hoped-for redemption of the Racer family. Connecting these timelines through radio announcers, bits of animation, and other visual bric-a-brac, all pushed forward by Michael Giacchino’s score, Speed Racer works hard to establish a deep bond between brothers—one that not even death can break. Speed Racer (Emile Hirsch) dreams of tearing up the tracks like his big brother Rex (Scott Porter), and we get scenes from his elementary-school days, when he’s so hopefully distracted that he bubbles in “Go Rex Go” on his exams. As Speed gets older and shows promise behind the wheel, the Wachowskis and their editors, Zach Staenberg and Roger Barton, fold past and present together by deliberately confusing Speed and Rex’s races. A line like “punch it for the jump” can whisk us from one brother to the other in cut, syncopating their actions.

When it’s revealed that Rex died in a terrible explosion against the side of a mountain, the news hits particularly hard, because the Wachowskis have so thoroughly associated his story with Speed’s. Still, his death has not stopped Speed from ascending the ranks of young prospects, which attracts the attention of E.P. Arnold Royalton (Roger Allam), the CEO of Royalton Industries, a major player in the racing world. Royalton gives Speed and his family a grand tour of his facilities, suggesting that only corporate sponsorship can help him achieve his goal of winning the Grand Prix. But the Racers have their own, independent shop, a literal Mom (Susan Sarandon) and Pops (John Goodman) operation, so Speed decides to turn Royalton down. Royalton does not take the decision well.

The battle between the Racer family and Royalton Industries is a David-versus-Goliath match-up that pits scrappy, independent artists against the remorseless beasts of commerce. The Wachowskis siding with the indies might seem a little ridiculous, given that Speed Racer is a Warner Bros. picture, as extravagantly appointed as Royalton headquarters. It's like Rage Against the Machine pushing radical politics through Sony. But baked into Speed Racer is the reality that a sport like racing can’t be done on the cheap, and so the road to integrity runs through a system that’s often hostile to those that don’t play along. For filmmakers who want to operate on a blockbuster scale like the Wachowskis—to rage inside the machine—that’s a workable metaphor.

Speed Racer also extends the conspiratorial thinking of The Matrix, both operating on the idea that free-thinking individuals are oppressed by a system that’s diabolically rigged. Much like Neo, there’s an easier path through life for someone like Speed, who can take Royalton’s offer and enjoy great comfort, ensconced in the luxuries of advanced-tech machines, guaranteed victories, piles of wealth, and private jets filled with candy for his little brother Spritle (Paulie Litt) and Spritle’s monkey companion. The hard route sets him against corporate forces that are more familiar to us than aliens mining humans for battery power. For Royalton, the stakes of the Grand Prix have to do with business rivalries and mergers and stock prices, which make victories too important to leave to chance. “It has nothing to do with cars or drivers,” he says of racing. “All that matters is power, and the unassailable might of money!”

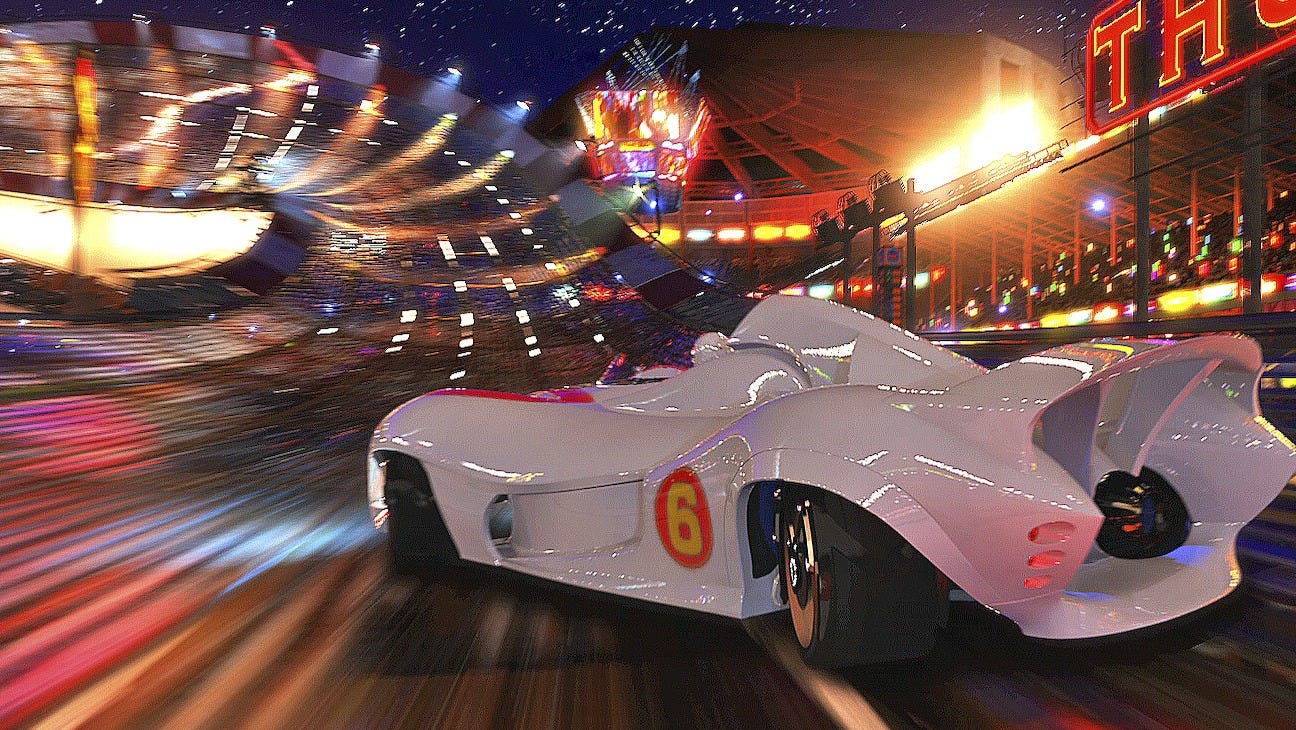

Rest assured, however, that Speed Racer is still about racing, and that the Wachowskis attempt a visual language for live-action that complements and extends the crude action on the animated show. Their most important conceit is to dispense of physics, the notion of cars as having any gravitational relationship to the track. The racers here reach speeds of 600 km/hr, and they have to negotiate impossible curves and slick surfaces, along with the demolition-derby mentality of rival drivers. There’s never a moment when the audience is asked to suspend their disbelief because the races take place in a realm of colorful abstraction that’s rare to see in live-action, but blithely accepted in animation. The Wachowskis and their effects team are painting entirely in CGI, not merely augmenting stunts with it. Speed Racer ran so the Fast and the Furious sequels could walk.

The Wachowskis pull off a neat double-twist with the introduction of Racer X (Matthew Fox), a masked driver who uncannily resembles a certain deceased sportsman, and touch on another theme of self-sacrifice for the greater good, which also echoes The Matrix. But it’s the visual aesthetic of Speed Racer that ultimately stands apart, culminating in a Grand Prix finale where Speed zips around a stadium track at night so quickly that the neon lights start to swirl and blur together and the car itself floats through space, achieving a kind of transcendence. As all the important people and memories and events of his life coalesce, Speed becomes Keir Dullea at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, pulled into a vortex of color that’s beyond imagination or rationalization. Feels like victory.

Next: Under the Silver Lake

I'm so excited to revisit this that I timed a trip to New York City next month (apocalypse permitting) around a screening of it at Nitehawk Cinema, introduced by noted Wachowski champions Griffin Newman and David Sims. Couldn't be more psyched. I recall walking away from it in 2008 with a sort of awed-but-muted appreciation, but as you note a lot has changed.

> Speed Racer ran so the Fast and the Furious sequels could walk.

Man, that is terrific line.