‘The Beginning or the End’: Oppenheimer Before ‘Oppenheimer’

In 1947, MGM released a film billed as the true story of the creation of the atom bomb. It wasn't.

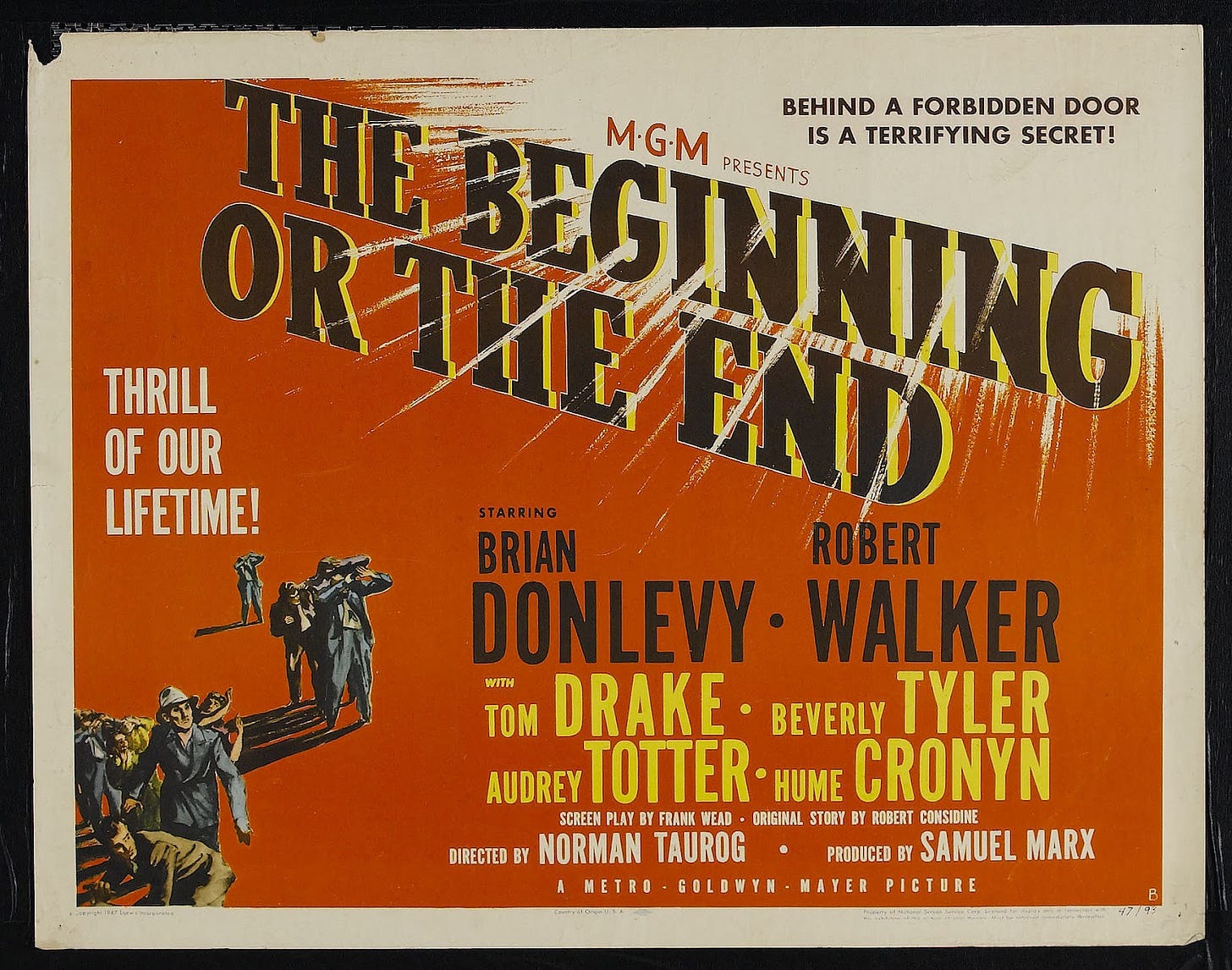

The Beginning or the End, the first film made about the development of the atom bomb, MGM’s ‘The Beginning or the End’ announces it’s not to be trusted with its first scene. Opening, a la Citizen Kane, with a newsreel, it depicts a gathering of “scientists and dignitaries” as they bury a time capsule at the foot of a redwood tree. The capsule contains a record of the atomic program, not to be opened until 2446, five hundred years in the future. Among its contents: a movie projector and The Beginning or the End, the film those in the audience showed up to watch. Those presiding over the entombment in this scene include General Leslie Groves and J. Robert Oppenheimer, only it’s not them but, respectively, Brian Donlevy and Hume Cronyn, the actors playing them in The Beginning or the End. Somehow the movie includes footage of its own burial.

Is this a post-modern head-scratcher or a lapse in logic that the film’s creators hoped audiences wouldn’t notice? Either way, it establishes the cavalier approach to the facts taken by an extremely serious film that’s hard to take seriously. Though released with much fanfare in 1947 after a production process that included everyone from Albert Einstein to Harry Truman, the film fell quickly into obscurity. But it’s fascinating as its own time capsule, capturing the American response to the atom bomb in the first years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the attempting to establish an official narrative about the bomb’s implementation that would inform attitudes for years to come. It’s a salve to the American conscience packaged as a hard-hitting docudrama.

That’s not necessarily apparent from the opening, however. After a title informing viewers “You are about to see the motion picture sealed in the time capsule for the people of the 25th century,” and credits that present it as “basically a true story,” the film pushes through the doors of Oppenheimer’s lab where the scientist—played by Cronyn with almost folksy friendliness—begins speaking to 25th century viewers in English (“now, and I hope in your time, one of the leading languages of the world”). He’s welcoming but also wary, noting “the people of my era unleashed the power that might, for all we know, destroy human life on this Earth. […] We know the beginning. Only you of tomorrow, if there is a tomorrow, can know the end.”

That ambiguity about the bomb proves to be a front. Historian Greg Mitchell’s excellent 2020 book The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, covers the film’s production in exacting detail, with an emphasis on how the film fit into the hardening of a widely accepted narrative: that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were unavoidable, the only way to end the war without an invasion that would cost half a million lives—a number that had a tendency to drift up over time. Made with heavy input from Groves, the Manhattan Project’s military director (played here by Donlevy, and later to be be played by Paul Newman and, most recently, Matt Damon), and tweaked with suggestions from the Truman White House (Truman himself provided the title), The Beginning or the End became part of that narrative, however much hand-wringing it contained

.It didn’t start that way. The film’s unlikely origins involve Donna Reed, whose high school science teacher Edward R, Tompkins worked at Oak Ridge during the bomb’s development. The two had stayed in touch, off and on, though more off than on in recent years because of Tompkins’ top secret work. With that work done, Tompkins suggested to his former student that it might make a good subject for a film. What began as an earnest attempt to tell the story of how atomic weaponry came to be quickly evolved. Treated as a major project by MGM, its production cycle was escalated by a rival film at Paramount. In time, MGM subsumed the Paramount project, which wasscripted by Ayn Rand and filled with warnings against statism. (The unexpected downtime helped allow her to write Atlas Shrugged, complete with its Oppenheimer surrogate). It ultimately emerged as a film sanitized for widespread consumption, designed more to influence the viewers of 1947 than to inform the citizenry of 2446.

Oppenheimer begins as the film’s narrator but soon drops back to a supporting role behind Matt Cochran (Tom Drake), a brilliant (and fictional) young physicist. Cochran becomes a kind of audience surrogate whose misgivings are assuaged at every step as he moves from the lab of Enrico Fermi (Joseph Calleia) through the Manhattan Project and finally to Tinian, the staging ground for the Enola Gay’s flight to Hiroshima. It’s there that Cochran contracts radiation sickness due to a mishap, but not to worry: he returns in spectral form in the film’s final scene. In the film’s howlingly silly final moments several characters read a letter Cochran left behind against the backdrop of the Lincoln Memorial. After the expected tearful sentiments the letter makes a point of stressing the many wondrous, and peaceful applications of atomic power that will make their still-unborn child’s life easier.

“We stand now,” he tells her from beyond the grave, “where the early savages stood when they ceased running away from fire and began to use it well. If those primitives learned to use fire, we of an enlightened century can learn to use atomic energy constructively. God has not shown us a new way to destroy ourselves. Atomic energy is the hand He has extended to lift us from the ruins of war and lighten the burdens of peace. Anne, you and our boy will see the day when the atoms in a cup of water will heat and light your home…” It just keeps going from there.

It’s a laughable finale, but what precedes it is quite watchable, the work of a major studio putting considerable resources behind an attempt to squeeze the story of the A-bomb into a fairly conventional World War II movie, in spite of its documentary flavoring. Directed by Norman Taurog—in the years between winning Best Director in 1931 and becoming the go-to director for Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis and, later, Elvis—the film zips along as fictional characters like Cochran and Col. Jeff Nixon (Robert Walker) brush shoulders with Groves, Oppenheimer, Enola Gay Pilot Paul Tibbets (Barry Nelson), and Albert Einstein. (All gave permission to be portrayed in the film. Oppenheimer and others even visited the set.)

Since scientific work can be a bit on the dull side, the film embellishes the story with some suspenseful nonsense, like an attempt to create an atomic chain reaction in Fermi’s Chicago lab filled with beeping monitors and other doodads. The studio also poured resources into special effects. Its depiction of the Trinity test is quite chilling, a moment of blinding light and pillowing smoke. The bombing of Hiroshima matches it, leaving Tibbets and his crew unsure how to respond. “Let’s get out of here,” the pilot says. “It feels like we’re over a dead world.”

Yet, for all its depiction of the fear and awe inspired by atomic power, at every step, The Beginning or the End attempts to soften the blow. Accompanied by a plane christened Necessary Evil, the Enola Gay dodges enemy fire on its way to Hiroshima, a city we’re told has been warned of an imminent attack via dropped leaflets for ten days. None of this is true. Also untrue: the assertion that the bomb dropped on Hiroshima—a city then heavily populated by women and children due to wartime—would primarily claim military victims. (Nagasaki’s bombing goes without depiction.) And though Truman demanded the scene in which he ordered the bombing be reshot because he felt like the film portrayed the decision as rushed and not deeply considered, this seems to be untrue too. In later years, Truman bragged about it not being a tough call at all.

The Beginning or the End drew mixed reviews—a rave from Esquire, some kind words from Variety, but not much else in the way of praise elsewhere—and did ho-hum business at the box office. But the story it told was just one part of a larger story being told elsewhere, one designed to squelch after-the-fact objections and downplay the horrors of the bomb. Christopher Nolan’s new biopic Oppenheimer doesn’t mention the film, despite its subject being aware of and even briefly contributing to the project. But at heart it’s haunted by it, not so much The Beginning or the End itself as what it represents, a reason to enjoy restful nights knowing that, however scary, the force just unleashed on the world would always be contained. Oppenheimer knew better, and so does Oppenheimer. It’s an invitation to contemplate the still-relevant nightmares others sought to suppress.

This sounds fascinating in a train wreck kind of way, but doesn’t appear to be streaming anywhere -- not even for rent. My local library has two copies of Mitchell’s book, though, which seems like it will be more edifying.

The scene where Cochren receives a fatal radiation dose is based on actual incidents during the Manhattan project. Physicists Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin were each exposed to fatal radiation during experiments with a just-barely-subcritical plutonium core (look up the "Demon Core" for details).