Tale of the Tape: 'Presumed Innocent' (1990) vs. 'Presumed Innocent' (2024)

Apple TV+'s mid-summer hit is the second adaptation of Scott Turow's bestselling legal thriller. How do the film and series compare?

In the opaque business of streaming platforms, where companies rarely release viewer metrics that would be context-dependent or outright misleading even if they did, it’s hard to know what original shows are successful or not. But there are plenty of indicators that Presumed Innocent, an eight-episode adaptation of Scott Turow’s 1987 legal thriller, was a big summer hit for Apple TV+, starting with the news that the service has ordered a second season—which, if you’ve seen the show, will take quite a bit of engineering to pull off. The Apple TV+ version, starring Jake Gyllenhaal and Ruth Negga, is classic water-cooler entertainment for the Brita filter age, the sort of whodunit you can speculate about endlessly with co-workers and friends. (And perhaps complain about later when the big reveal is finally dropped.) But it also plays against memories of Alan J. Pakula’s 1990 film of Presumed Innocent, which kicked off a decade loaded with legal thrillers and featured a twist in the denouement so memorable that the TV series opted to manufacture its own. Both Presumed Innocent the movie and Presumed Innocent the show are flawed yet compelling takes on Turow’s book, and they offer a rare opportunity to compare both their distinct creative choices and how well the mediums themselves serve the material.

Here’s the basic premise for both: When the body of Carolyn Polhemus, a prosecutor in fictional Kindle County, is found tied-up and bludgeoned in what appears to be a bondage session gone wrong, district attorney Raymond Horgan assigns the case to his right-hand man, Rozat “Rusty” Sabich. But the aging Raymond is locked in a bitter re-election fight against the ambitious Nico Della Guardia, and when the election turns in Della Guardia’s favor, the Polhemus case takes a dramatic turn, too. Della Guardia and his own right-hand man, Tommy Molto, charge Rusty with Polhemus’s murder, citing it as a crime of passion over an office romance that fell apart and inspired a deadly obsession. The case is particularly wrenching for Rusty’s wife Barbara, who’s in the awkward position of standing by her husband while still reeling from his betrayal.

I’m going to try to keep things vague for those who haven’t seen the film, the series, or both. Let’s see how they break down:

Presumed Innocent (1990) vs. Presumed Innocent (2024)

The Cast

Rusty Sabich: Harrison Ford (film) vs. Jake Gyllenhaal (series). The biggest point of contrast between the two Presumed Innocent projects comes right at the top. Ford and Gyllenhaal are temperamentally different actors and they bend the role in their own direction. At the time, Ford’s confidence in his own movie-star magnetism was leading him to sleepwalk through dramatic roles, underplaying them to the point of lifeless self-effacement. He seems in danger of doing so again as Rusty, who accepts the charges against him so blithely that you don’t know if he’s tormented or in need of an afternoon nap. But at key moments in the film, there are cracks in the façade, as Ford reveals the emotions that Rusty has bottled up inside, not least his love for the deceased, which fills him with grief and shame simultaneously.

Gyllenhaal, on the other hand, runs hot. And the show follows in kind. His Rusty is an aggressive, impulsive, and often foolhardy man who gets himself into trouble and seems convinced he’s the only one who can get himself out of it, even if he occasionally opts to represent himself at trial. He is the opposite of Ford’s Sabich. He keeps virtually nothing under the hat, to the point where everyone in the office and in his family seemed to know about his marital indiscretions, but also to the point where the people closest to him are assured he’s not capable of murder. His passion is the engine that drives this eight-episode series forward, and its twists seem to hinge on Gyllenhaal’s volatility. Advantage: Draw.

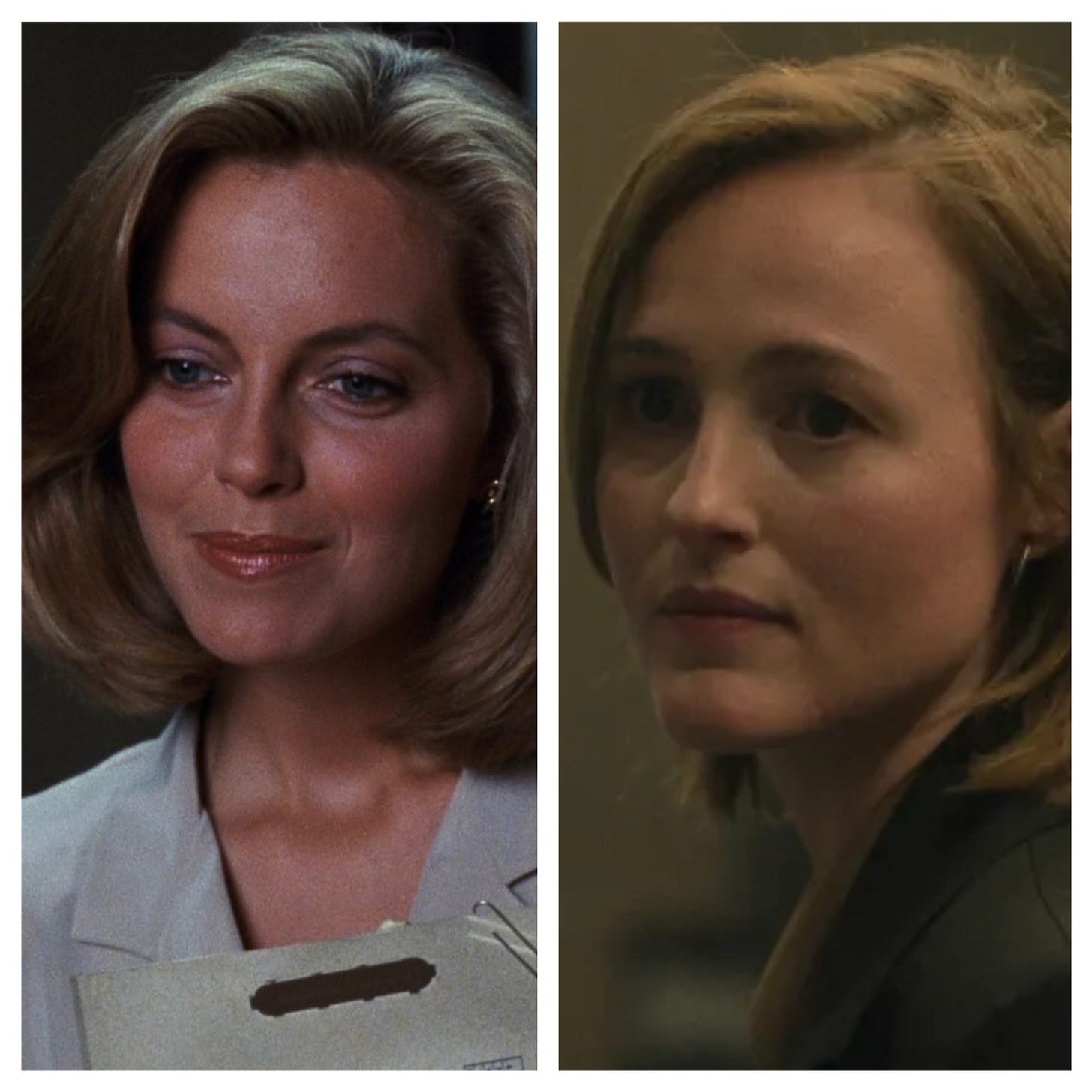

Barbara Sabich: Bonnie Bedelia (film) vs. Ruth Negga (series). Just a year off playing another dissatisfied wife in Die Hard, Bedelia has a wry, understated acting style that syncs well with Harrison Ford. Her soft-spoken quality seems intended to draw her back into the woodwork, save for a few quiet barbs at Rusty’s expense. Yet a scene where Barbara dresses up in new lingerie before her distracted, disinterested husband allows Bedelia to show the real anguish his affair has caused her, which is critical in setting up the ending.

But with all due respect to Bonnie Bedelia, she is not Ruth Negga, one of the greatest actresses alive. Eight episodes gives the series’ cast plenty of real estate to do their work, and the bulked-up role for Barbara gives Negga the opportunity to let it rip. The scope of Rusty’s betrayal in the series is expanded in the series, too, as revelations about the affair trickle in, all underlining the plain fact that he loved Carolyn to her last breath and continued to be willing to put his marriage and family on the line for her. (The series gives the Sabichs two teenage children with major roles, as opposed to a young, pre-King of the Hill Jesse Bradford in the film.) Negga lays her humiliation and agony bare, but Barbara’s instinct to defend Rusty and keep her family whole gives the performance that much more dimension. Everything good about the series starts with Negga. Advantage: Series.

Raymond Horgan / “Sandy” Stern: Brian Dennehy and Raul Julia (film) vs. Bill Camp (series). One of the major changes from film to series is the consolidation of two characters into one. In the film, Dennehy plays Rusty’s mentor and boss Raymond Horgan, but bitterness over his own affair with Carolyn, along with Rusty’s suspicious handling of the case in its early hours, turns him into a witness for the prosecution, despite his political battle with Della Guardia. In the series, Raymond steps down after losing the election and confirms his allegiance to his “best friend” Rusty by serving as his defense attorney, a separate role played brilliantly by Raul Julia in the film. The character-actor-off between Dennehy, Julia, and Camp naturally ends in a draw, as they’re all excellent, though Camp has much more time than Dennehy to strut his dyspeptic stuff. But as much as Julia brings a different flavor to the role of Rusty’s lawyer—his brightness counters Ford’s gruff introversion, and gives the film much-needed comic relief—the decision to expand Raymond’s part streamlines the series, enhances Camp’s performance, and sets up a rivalry with Della Guardia and Tommy Molto that carries over from the election to the courtroom. Advantage: Series.

Tommy Molto: Joe Grifasi (film) vs. Peter Sarsgaard (series). Not a close contest here. The Tommy Molto of the film is a minor role, nicely played by Grifasi, but not as deeply enmeshed in any personal animus between Tommy and Rusty or Tommy’s own odd obsession with Carolyn. It’s almost a shame that the series insists on making Tommy the office creep, because Sarsgaard’s performance in the courtroom recalls his signature role as Chuck Lane in Shattered Glass, where he steadily eviscerates a soft target. The case against Rusty is stronger in the series than in the film—albeit still based on circumstantial evidence—and it ends in a verdict that’s very much up in the air, thanks in part to Tommy’s tough questioning, even when it strays into uncomfortably personal territory. Advantage: Series.

Carolyn Polhemus: Greta Scacchi (film) vs. Renate Reinsve (series). Best known for her work in Joachim Trier films like Oslo, August 31st and The Worst Person in the World, the Norwegian actress Reinsve is another casting coup for a series loaded with them. For obvious reasons, both women are presented in flashbacks, but the series undermines Reinsve with an annoyingly elliptical style that presents Carolyn in drips and drabs, robbing her of any complexity. It seems obvious that the show wanted to get some distance from the film’s depiction of Carolyn as a power-hungry prosecutor who wasn’t above using her sexuality to get ahead in the field. (She drops Rusty when she has no other use for him.) Yet the film gives Scacchi actual scenes to heighten both her femme fatale allure and her genuine excellence on the job, suggesting that maybe she wouldn’t have to leverage her body if the prosecutor’s office was more of a meritocracy. Advantage: Film.

Plotting/Themes

Frank Pierson and Alan J. Pakula (film) vs. David E. Kelley and co. (series). Presumed Innocent the film is 127 minutes. Presumed Innocent the series is about 350 minutes. (Though it’s worth noting the show keeps it tight, relatively speaking. Most of the episodes hover between 40 and 45 minutes and only the finale gets up to 50.) So not only does the show have to expand the story considerably, it has to get some distance from a hit film and a bestselling novel that’s too embedded in popular culture to repeat without viewers getting bored or feeling too far ahead of the action. For better or worse, mostly worse, this is David E. Kelley’s time to shine. A prolific veteran of medical shows (Chicago Hope), legal shows (Ally McBeal, The Practice), melodramas (Picket Fences), and limited series (Big Little Lies), Kelley knows how to stir the pot and stir the pot he does, with plotting that amps up the conflict on all fronts and ends every episode with a cliffhanger. His Presumed Innocent affirms his instincts as a reliable TV hitmaker: You can pop episodes of this show into your mouth like bonbons, and have a great time with the performances and the odds-making over the many suspects on offer, which are bountiful tin packed with red herrings, including Rusty, Barbara, Tommy, a guy in jail, a guy who might have done the crime the guy in jail did, Carolyn’s creepy son, Carolyn’s creepy ex, and Carolyn’s creepy cat.

Yet the focus on the whodunit mystery—and the mostly unsatisfying unmasking—leaves the series on a profoundly hollow note, as if it never had anything else on its mind. The film version has its own unmasking, of course, but as with Pakula’s great ‘70s paranoid thrillers The Parallax View and All the President’s Men, the failure of American institutions and its powerful stewards to achieve justice is more important than the actual case. There should be some sort of justice for Carolyn Polhemus and the evidence against Rusty is enough to make him a legitimate suspect, but the trial ends in an abrupt dismissal, owed to behind-the-scenes corruption and blackmail that has nothing to do with the victim whatsoever. (It’s a nasty irony that Pakula bookends the film with austere shots of a jury box, when the jury doesn’t end up having a voice.) Kelley has more time to whip up the drama in the prosecutor’s office, but the film uses the framework of a standard legal thriller to question how well the system actually works. It’s a bleak and subtly subversive indictment of the system, packaged in the familiar guise of a legal thriller. Advantage: Film.

Direction

Alan J. Pakula (film) vs. Anne Sewitsky and Greg Yaitanes (series). Film is a director’s medium, and though Pakula was well past his Klute/The Parallax View/All the President’s Men prime, much of what distinguishes Presumed Innocent from the glut of ‘90s legal thrillers that followed is owed to his sensibility. With an assist from an excellent John Williams score, Pakula emphasizes the austerity of judicial institutions before picking away at the rot that undermines them. He also suggests a sinister intimacy between Rusty and Barbara that locks them into a marriage that Rusty’s infidelity violated. The system cannot access the truth behind Carolyn Polhemus’ murder but the Sabiches are condemned by it, and Pakula puts the domestic and courtroom dramas in conversation with each other.

The direction on the series is mostly high-end Apple TV+ gloss, save for those irritating flashbacks to Carolyn, which make you grateful that Sewitsky and Yaitanes keep the stylistic trickery to a minimum. Turow’s novel takes place in fictional Kindle County, a stand-in for a Midwestern city like Chicago, though the film was shot in Detroit and Ontario and the specific location of this everycity is never identified. The series is set firmly in Chicago, but it only evokes the city through standard drone and second-unit exteriors, which is a typical cost-saving measure for television, but signals a lack of care here. Advantage: Film.

Ending

This character did it (film) vs. No, that character did it (series). To keep this as vague and unspoiled as possible, the ending of the film is undoubtedly its most memorable stretch, with a chillingly casual reveal in what we assume to be the denouement. The series opts not to repeat it, which means coming up with an alternative killer among an extended list of suspects. The person it lands on gets a big LOL from me, though the big scene is a terrific showcase for Negga, who legitimizes the reveal with a great outpouring of emotion. Her work is a reminder that we have an abundance of acting talent in Hollywood. The material just needs to be better. Advantage: Film.

Overall Winner

Presumed Innocent (1990).

Wow, Dennehy, Julia and Camp. That role has become Hamlet-esque in the number of heavy hitting actors who have inhabited it! Seriously, quite a murderer’s row.

"Ruth Negga, one of the greatest actresses alive"

I love reading a line like this, going to look at their credits and realizing I haven't seen anything this person has been in