Simply Having a Wonderful Kubricktime

Why Stanley Kubrick's 'Eyes Wide Shut,' a tale of sexual jealousy and class barriers, deserves to be a Yuletide tradition.

For his brilliant 1975 period piece Barry Lyndon, director Stanley Kubrick wanted to bring the world of upper-class 18th century Europe to authentic life, which presented the immediate problem of lighting the interiors of immense homes that were over 100 years away from the invention of the lightbulb. This was difficult enough during the daytime, when at least the sun could bring natural light through the windows, but Kubrick famously insisted that dark rooms be illuminated by candlelight. The effort involved a special, modified NASA lens that could operate in low light and immense amounts of heat and smoke that sucked up oxygen during production, but it yielded one of the most beautiful films of its era, a painterly epic that’s significantly more immersive than it might have been otherwise.

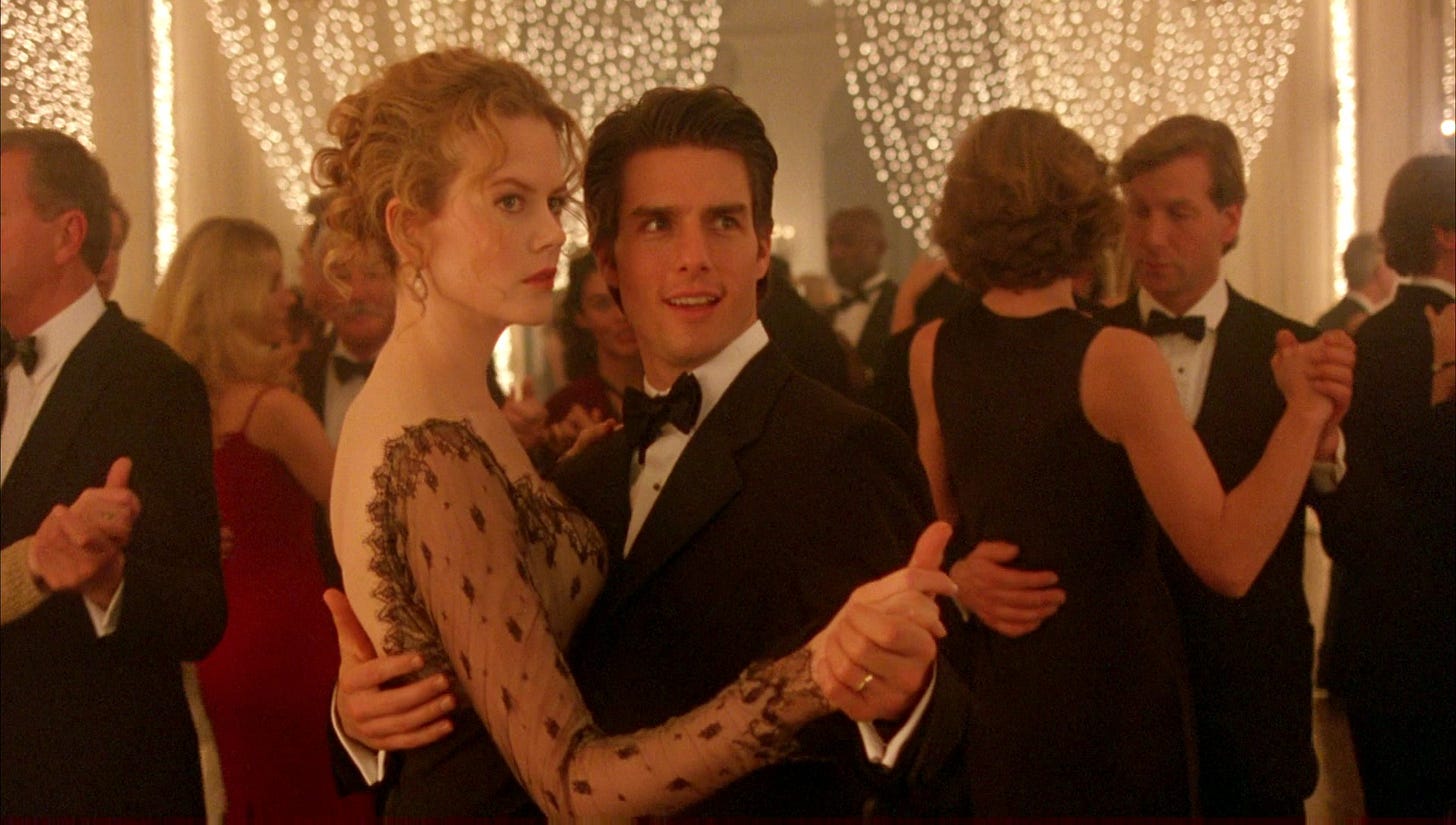

Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut, presented no such challenges because it takes place during present-day Christmastime. There are Christmas lights everywhere, casting an impossibly radiant glow around the living rooms and staircases of Manhattan’s wealthiest elites and decorating storefronts throughout the city. There are Christmas trees tucked in all the corners, too, including the grim bedroom of an elderly patient who’s just passed away. People tend to get needlessly pedantic about what films do or do not qualify as “Christmas movies,” but in the great cinematic subdivision of movies that take place during the holidays, Kubrick occupies the cul-de-sac where all the neighbors bring their guests, because his display could probably be seen from outer space. “How did they find the time to put all those lights up?” one might ask. “They must have froze their asses off.”

The holiday setting isn’t accidental. Nothing in a Kubrick film ever is. Though the theories around a film like The Shining can get a bit baroque—as documented in the terrific documentary Room 237—there’s no missing the deliberateness of Christmas as the backdrop for this dream-like odyssey of sexual jealousy and modern-day social mores. Perhaps the most fundamental shift, in fact, is Kubrick’s decision to shift the setting of his source material, Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 novella Dream Story (or its much cooler German title, Traumnovelle), from early 20th century Vienna to late-‘90s New York City, and to convert its protagonist from a Jew to a gentile, played by the extremely non-Jewish Tom Cruise. Christmas means something to the couple at the center of Eyes Wide Shut, who are busy fussing over presents when they aren’t in the throes of a marital crisis, and it’s a more important part of the film than mere decoration.

Prompted by his wife’s startling confession of desire for another man, Dr. Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) embarks on a long sexual misadventure in New York that isn’t so dissimilar from those taken by Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol or George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life—two works, we should note, that have never have been in dispute as holiday classics. Christmas is a time when people are expected to appreciate their loved ones and cherish the lives they’ve built for themselves, but Harford, like Scrooge and Bailey, is restless and unmoored, and in need of outside intervention. While he may not be visited by supernatural interlocutors, the New York of Eyes Wide Shut seems a little like the one in Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, a nocturnal force that’s exacting a punishment on him that he doesn’t think he deserves. There are conspiracies abound in the film involving the city’s most powerful people, but there also seems to be a quieter one underneath, like a collective effort to teach the reeling doctor a few lessons he can bring back to a healthier marriage.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Reveal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.