Revisiting 'The Book of Movie Lists,' an Eccentric Collection of Odd Facts and Bizarre Opinions from the Long-Ago Year of 1981

I tracked down a book I checked out from the library years ago. It was a lot weirder than I remembered.

Like most people, my head is cluttered with odd bits of knowledge that I’m not sure where I picked up. I was born squarely in the middle of Gen X, a generation that straddles the digital divide. I received my first email address — and my introduction to the concept of email itself — my freshman year of college but didn’t visit a website until I graduated college. (I have a distinct memory of typing a long URL for an X-Files fan site printed in Entertainment Weekly and taking two or three tries to get it right.) Now I reach for my phone when I can’t remember, say, what year the second Matrix movie was released, like just about everyone else. But it wasn’t always so.

Was the old way better? Probably not. It’s easy to romanticize the past but also easy to forget how flawed the old ways of learning could be. I devoured, for instance, a 1977 collection called The Book of Lists and its two sequels written by David Wallechinsky, Irving Wallace and Amy Wallace, spin-off books from something called The People’s Almanac. That sounds like an authoritative source. Little did I realize that Irving Wallace was the novelist behind bestsellers like The Man and The Seven Minutes, Wallechinsky and Amy Wallace were his children, and that, beyond sharing a seemingly insatiable curiosity, their claims on any kind of authority about, well, anything, were pretty sketchy.

That may also help explain why they were so entertaining. The Book of Lists and its sequels mixed good information with bad and the sort of fun facts that help turn kids into future trivia champions alongside a rundown of the most popular sexual positions and salacious and dubious info about Catherine the Great and her fondness for horses. All that flood of information took the form of lists of varying size, and usually of some odd number. They’re little discussed today, but I know I wasn’t the only one to sponge them up. John Hodgman, for one, has talked about them as inspirations for his The Areas of My Expertise and its follow-ups. They were certainly a big influence on The A.V. Club’s Inventory feature, which (and I don’t think this is immodest) in turn influenced the way a lot of websites approach lists. Even now, a healthy percentage of my writing work takes the form of lists and The Book of Lists remains a foundational text for that work, even if I haven’t looked at it since I was in junior high.

The Book of Lists was successful enough in its day to inspire imitators, including the 1981 collection The Book of Movie Lists, written by Gabe Essoe (who published it simultaneously with The Book of TV Lists). I devoured that, too, and, spurred by the memory of poring over its pages, I decided to order a used copy and revisit it. What arrived is a much stranger book than I remembered.

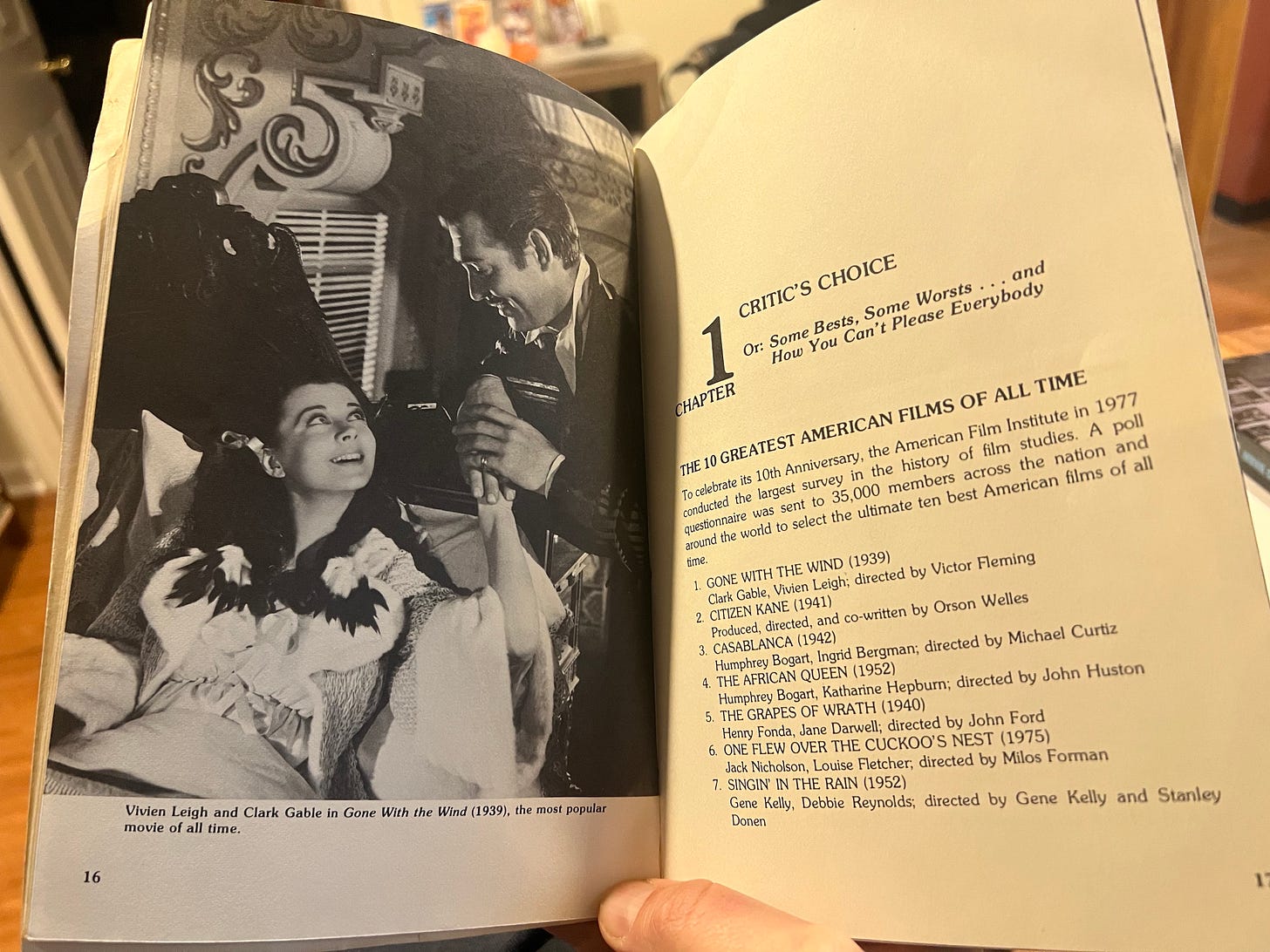

Essoe wasn’t a household name then and isn’t now. He’s best known for writing the screenplay to the William Shatner-starring 1975 horror film The Devil’s Rain and co-writing the story to the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode “Sanctuary” (that’s the one where the station plays hosts to a bunch of refugees from the Dominion) with his wife Kelley Miles, daughter of Vera Miles. But Essoe also worked as a journalist, work that included contributions to the Los Angeles Times, and wrote a biography of Clark Gable and a book on Tarzan movies. And, if The Book of Movie Lists is any indication, he had a pretty thick Rolodex.

Much of The Book of Movie Lists appears to be the result of phone calls with famous people who didn’t want to say no but didn’t really have that much time to spare. Thus, an item like “Buddy Ebsen’s List of the Dancingest Feet in the Singin’ and Dancin’ Movies of Hollywood’s Golden Age” consists of a long wind-up and then nine names accompanied by short assessments of what made them notable. (Eleanor Powell: “She sure had vitality, and legs to knock your eyes out.” Shirley Temple: “You know, for her age, she was a great little hoofer.”)

Other contributors include Clint Eastwood, George Kennedy, Melvin Belli, Mario Andretti, Vera Miles (of course), Ernest Borgnine (who also supplies the intro), and Mae West. Some lists include precious little commentary. John Ritter, for instance, just puts the word “Naturally” next to his dad Tex Ritter’s name on his list of “6 Favorite Childhood Western Heroes” then the names of five other favorites.

By contrast, Church of Satan High Priest Anton La Vey expounds at length on the actors he chose for his list of “10 Highly Satanic Screen Portrayals.” If La Vey’s list were published online today, it would be easy to attach a “#1 Will Surprise You!” teaser. But, honestly, numbers one through ten are all pretty surprising. Edward G. Robinson holds the top two slots for, respectively, The Sea Wolf and Key Largo but La Vey also finds room for George Sanders (“a satanist par excellence in practically everything he did”), Peter Cooke, and Ernest Borgnine (for his work in The Devil’s Rain).

Essoe fills out the chapters with straightforward lists of history’s all-time highest-grossing movies but also out-of-nowhere looks at, say, the top-grossing films in Hong Kong in the first nine months of 1980. (A big hit alongside the homegrown action movies: Kramer vs. Kramer.) Alongside the raw facts are some truly bizarre selections, puzzling bits of editorializing, and a nostalgia for yesteryear that suggests an unexamined (small “c”) conservative streak.

How strong a conservative streak? Essoe devotes four-plus pages to a list of film banned by the Catholic Legion of Decency with quite a few entries that nod in agreement (Dressed to Kill is a “perfectly loathsome little movie,” for instance) before concluding with a lament for the organization’s dissolution in 1980. (“We have lost a valuable watchdog.”) Essoe includes a contribution from Erica Jong but can’t bring himself to use her trademark phrase, “zipless fuck,” opting for “zipless sexual encounter” instead. (Per Jong: “There aren’t any zipless love scenes in the movies.” At zero entries, hers is the shortest list in the book.)

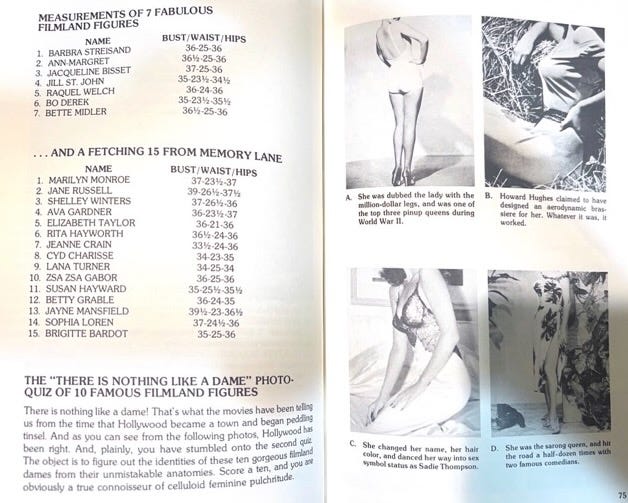

That doesn’t prevent The Book of Lists from indulging in a lascivious streak, including a list of famous actress’s measurements and headless publicity shots of female stars’ bodies that asks readers to identify from their curves and a list of those “linked romantically” with John F. Kennedy. The book also gives a whole page to a pre-fame nude photo of Marilyn Monroe (“37 - 23 1/2 - 37”) accompanying another La Vey list, this one dedicated to “3 of Marilyn Monroe’s Attributes Which Ironically Led to Her Evolvement into the Supreme Sex Goddess.”

Having first checked this book out from the library at the age of twelve or thirteen (a few years after its publication) I remembered that page, if not the context, quite well. But rereading Essoe’s book, I was surprised by how much other parts of it had seeped into my brain and stayed there. I’ve never seen The Conqueror, but I did know that those who worked on the movie, which filmed near the site of nuclear tests, suffered an unusually high rate of cancer. I remembered that Stephen King thought the garden trowel scene in Night of the Living Dead was one of the “6 Scariest Scenes Ever Captured on Film” and that Ronald Reagan almost starred in Casablanca.

But, here’s something: that oft-reported "fact" isn't true. The Book of Movie Lists also includes a lot of other dubious, if of its time, editorializing alongside such occasional bits of misinformation. L.A. Times critic Charles Champlin’s list of the greatest films of all time describes The Birth of a Nation as a must-to-include “racist as we may think it now.” (You certainly can’t wave away its importance, but you can’t dismiss the racism that was always there and much commented-upon at the time so easily, either.)

Essoe also has a particular distaste for Robert Altman. Several lists, including a fawningly introduced guest contribution from the once-ubiquitous (and obnoxious) gossip columnist Rona Barrett, make jabs at Altman’s recent bomb HEALTH and Essoe himself contributes “The First Annual ‘Waste of Film’ Festival Featuring 10 Robert Altman Losers.” Said losers include The Long Goodbye (“Elliott Gould tries real hard but can’t overcome the lack of directi0n”) and California Split (“just another futile exercise in excess”).

There’s a similar strand of meanness that runs through many of the lists, which include contributions from Mr. Blackwell, the late author of an annual worst-dressed list that always got a lot of play in the press for some reason, and Laurence J. Peter, the creator of “the Peter Principle,” the theory that individuals tend to rise to their level of incompetence. Hollywood examples, per Peter, include Steven Spielberg (whose most recent film was 1941), John Travolta, and, you guessed it, Robert Altman.

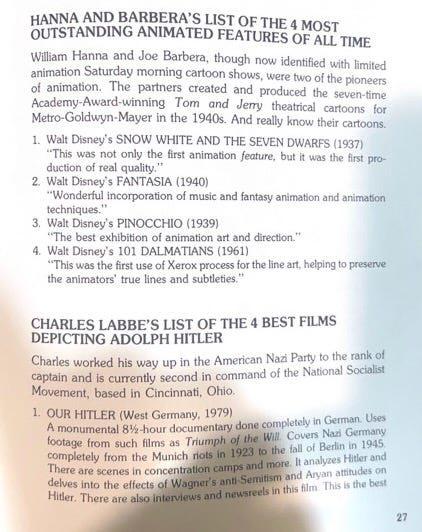

Then there’s this: appearing directly after a list of Hanna and Barbera’s favorite animated features, you’ll find a list of the “4 Best Films Depicting Adolph [sic.] Hitler” and several companion pieces like “The 2 Best Fictional Films About Post-World War II Nazis” — lists written by a member of the American Nazi Party. I keep trying to figure out how such a list was published in a book widely distributed enough to end up in a library in the suburbs of Dayton.

Is it too simple to suggest that the editorial standards of its publisher, Arlington House, might not have been wary enough about opening that door because its output mixed showbiz books and jazz discographies with conservative texts like Soviet Conquest from Space and None Dare Call it Witchcraft. (Probably? They also published some more respectable conservative writers.) Forty-plus years later, it’s shocking to see an actual Nazi opining about movies alongside Robert Osb0rne and Dennis Weaver. Was it not considered shocking then?

Also bizarre: the grim postscript to “Johnny Weismuller’s 9 Favorite Movie Tarzans”:

Revisiting The Book of Movie Lists dulled some of my affection for it, but that doesn’t mean I’m not still grateful it exists. Essoe’s book and books like it helped spark an interest in movies past and a sense of a long, rich history that I could explore. And that’s the thing about pop-culture lists: they should be gateways pointing readers in directions they might not otherwise have ventured. They’re there to provoke and to be argued with, not to serve as definitive statements. And sometimes they’re designed to trick readers into learning something, even if doing so first means beckoning them down a lurid path. Come for famous stars’ measurements or a psychic’s claims about who stars were in past lives, but if you stick around you might get curious about the Nicholas Brothers, whose dancing Debbie Reynolds revered, or discover which voice Mel Blanc most enjoyed doing.*

* It’s Porky Pig. I’m not going to make you track this book down to find out the answer.

My parents had a 1973 coffee table book called The Great Movies (not Ebert's – this one was written by William Bayer) which was pivotal to little me, featuring blown-up film stills and production photos from a list of movies which largely stands up today. I wasn't aware of any movies beyond what I saw advertised on TV, or what my parents took me to, so learning of the existence of such movies beyond my narrow experience was profound. In the internet age, I wonder about where the equivalents of books such as this, or movie lists, Maltin guides, Shipman's The Story of Cinema, etc., might be stumbled upon by accident, and have the same kind of impact on a young mind: perhaps it does happen, but the old man in me finds it difficult to draw an emotional equivalence between thumbing through the IMDB Top 250 versus perching over a heat vent, curled up in a blanket, shining a flashlight at a picture of a donkey and puzzling out why some guy in France would make a movie about him (unless he was a TALKING donkey, of course).

This is fantastic! Not necessarily inclined to get the book but extremely glad I read about it. It’s a great piece.