Minding the Gaps: 'Cruising' (1980)

In 1980, William Friedkin provoked outrage with a lurid thriller set in New York's leather scene.

Minding the Gaps is a recurring feature in which Keith Phipps watches and writes about a movie he’s never seen before as selected at random by the app he uses to catalog a DVD and Blu-ray collection accumulated over the course of the last 20+ years. It’s an attempt to fill in the gaps in his film knowledge while removing the horrifying burden of choice. This is the fifth entry.

What’s to be done with films that are morally reprehensible (or contain some deeply reprehensible elements) but artistically vital? I have no one-size-fits-all answer, only examples that, for me at least, make the question more complicated. Take Blake Edwards’s 1968 film The Party. On the one hand, it’s probably the director’s masterpiece, a brilliantly staged string of comic set pieces that’s the closest Hollywood ever came to making a Jacques Tati film. On the other, it stars Peter Sellers under brown make-up adopting a broad accent to play a bungling Indian character. If that was ever a sound idea (it wasn’t), it’s so far removed from contemporary sensibilities to make The Party a really hard sit these days. It’s hilarious and inventive. But is it watchable? (On the other other hand, it was a big hit in India at the time, and Satyajit Ray was a fan. These matters get complicated.)

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

Stereotypes and brownface aside — and what a clause that is to follow with the word “aside” — there’s never any sense of hatefulness within The Party. I’m not sure I can say that about William Friedkin’s 1980 film Cruising, a murder mystery set against the backdrop of New York's West Village leather scene. Before we get to that, here’s an insight on the problem of problematic films from a 2021 Vox article by my friend Emily St. James. This passage sticks with me as I think about Cruising:

Silence of the Lambs is a perfect movie — except it’s also a movie that helped perpetuate one of the worst, most transphobic stereotypes of all. I can hold these two ideas in my head, but when it comes time to talk about the movie, especially on social media platforms, it’s far easier to simply dig in my heels and argue either “I love this movie!” or “This movie is transphobic!” without leaving room for nuance.

There has to be a better way.

Emily is a trans woman who elsewhere notes that “to say seeing Silence at a formative age made accepting my own transness harder would be an understatement” but also that “Silence of the Lambs gave me a framework to think about myself before I knew who I was in the way it treated Clarice Starling, a woman cast adrift in an ocean of men. It treated Buffalo Bill like a human being.” All of these things can be true at once without negating each other.

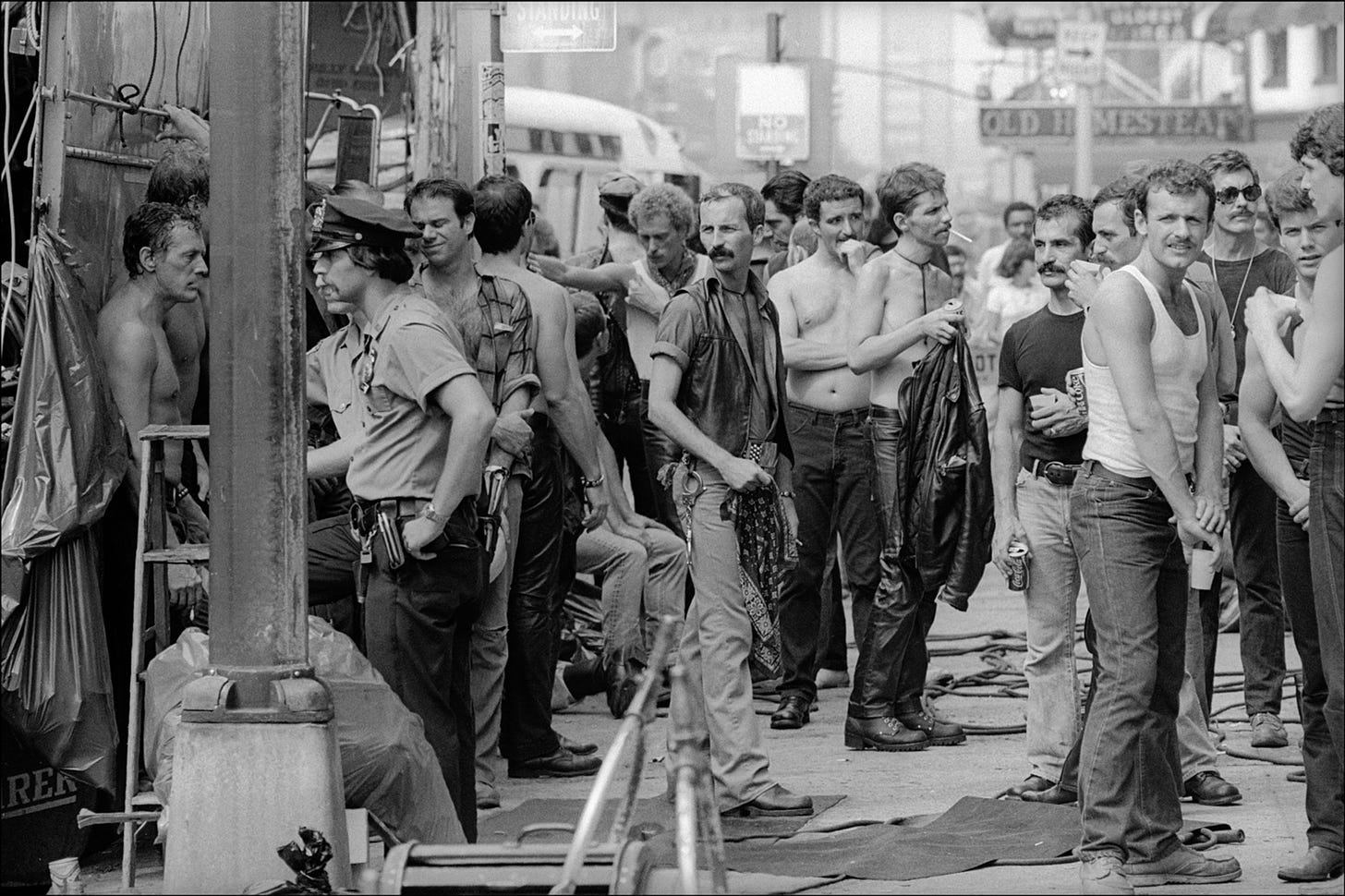

Cruising is not a perfect movie. In fact, I don’t think I like it very much at all. It was made in 1979 amidst protests spurred by Village Voice writer Arthur Bell, who feared it would be “the most oppressive, ugly, bigoted look at homosexuality ever presented on the screen.” He encouraged his readers to disrupt the production whenever they could, and they took him up on the challenge. Much of the dialogue is ADR in part because of the screaming, trash can-banging, and horn-blowing.

It’s always an iffy thing, judging a piece of art you’ve never seen, much less one that’s not even complete. But was Bell right? Well, it’s hard to say he was wrong.

Al Pacino stars as Steve Burns, an ambitious New York cop who takes an undercover assignment in pursuit of a serial killer who’s targeting athletic, dark-haired leather club habitués. (Al Pacino types, in other words.) He takes an apartment in a gay neighborhood and starts checking out the night life, doing his best to conceal his shock at what he sees in the clubs or when a convenience store salesman (Powers Boothe, in an early-career one-scene role) explains the color coding system of the scarves he sells. (“The green hankie in your right rear pocket means you're a hustler. The green hankie in your left rear means you're looking to buy. The yellow hankie in your left rear pocket means you give golden shower…” etc.) But shock isn’t the same as repulsion, and Steve starts to find himself stirred by his new beat.

No dialogue comments on this, we’re never shown what happens when Steve wanders off with other men at the end of scenes, and Steve seemingly never admits his new (?) feelings to himself. If you’re not paying attention, you might miss this subtext entirely. Friedkin bakes ambiguity into the film in ways that are stylistically fascinating but also kind of gross. Though they speak in the same overdubbed voice, different actors play the killer in each murder scene. (Shades of Zodiac.) Is there more than one killer? Is it a comment on the way participants in the scene lose their identities in the roles they play? Or is it a not-so-subtle equation with the leather scene—and homosexuality in general—with death? The film’s infamous climax—and, yes, spoilers ahead —suggests that Steve might have become a killer. Or maybe he was the killer all along?

Ultimately, Cruising ambiguous-es itself to death. It makes villains of homophobic cops who harass cross-dressing sex workers (and demand sexual favors of them) and depicts Steve’s gay neighbor (and maybe love interest?) Ted (Don Scardino) with tremendous sympathy— if not enough sympathy to avoid turning him into the trope of a tragic, doomed gay man. But it mostly wants to gawp at what it sees, lingering on lurid details in ways that feel designed to shock rather than invite consideration. As Phil Nobile Jr. put it in a 2012 look at the film, the “extreme subculture is more exploited than explored.” In 1980, depictions of gay sexuality of any kind in mainstream films were pretty rare and usually pretty tame. Though less explicit in the released version than in Friedkin’s original cut, Cruising drops viewers in the deep end with explicit depictions of an intentionally insular gay subculture. Today, a thriller set in a gay nightclub scene would be one of many depictions of LGBTQ+ existence. Unschooled viewers in 1980 with no point of comparison were given no reason not to mistake it for the whole of LGBTQ+ existence by a film that invited them to view it with, at best, wariness and suspicion. (Even the terminology making distinctions between L, G, B, T, Q, and + wasn’t in place yet.)

On the other hand, and there’s seemingly always another hand in these situations, Cruising is a remarkable document of a particular corner of the New York underground made by a hell of a skilled director. For extras, Friedkin drew on authentic members of the S&M crowd—those who weren’t protesting—and shot the film at the mafia-owned gay clubs that served as locus of the scene. (Those that didn’t refuse permission on principle, that is.) There’s a haunting beauty, too, to the way Friedkin shoots the park used for after-dark hook-up locations, and the murder scenes play as disturbingly as parts of The Exorcist. The film has been reassessed (and sometimes defended) over the years, and it’s doubtlessly benefitted from becoming a piece of history rather than a work whose implications for the here and now make it dangerous. Is it a good movie? Can a movie be good but also kind of evil at once? I don’t know. But I do believe it’s better to look at it and try to figure that out rather than look away.

Next: Death Valley (1982)

Quick data point on The Party, seconding your take:

I saw The Party as a 10-ish year old in India around 1989-90. And I thought it was uproariously funny. And no one (or at best almost no one) in my lefty-radical and culturally savvy family in India thought it was all that problematically racist. It was only later, after coming to the US that I realized it was (not incorrectly) considered a racist portrayal. But I still think it’s perfectly fine to enjoy the humor in it (which is genuinely great) as long as one isn’t blind to its problematic aspects.

Meanwhile, I still haven’t seen Cruising and need to rectify that.

I think this film is something of a spiritual godfather to the New Queer Cinema of the 1990s; like the other main influence on that later movement, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, this is not about “positive images” of homosexuality; rather, it is exploring what queer desire looks like within a homophobic and repressive culture. For a sympathetic reading of the film from a gay scholar, check out the chapter in David Greven’s book PSYCHO-SEXUAL: MALE DESIRE IN HITCHCOCK, DEPALMA, SCORSESE AND FRIEDKIN (2013)