Memories of a Forgotten Multiplex

Some reflections on working at an AMC theater in the late '80s and early '90s, and what we take away from long-gone spaces.

We don’t always know which moments will change the trajectory of our lives forever, but I’m certain of this: You would not be reading this if Toys ‘R Us considered me up to snuff.

A few months after my 16th birthday, my parents pushed me to find some kind of part-time work, not so much for the money—in 1987, the minimum wage in Georgia was $1.25/hr., though it would tick up to $3.25 the following year and remain there until… uh… 2002—but for the experience of being part of the working world. What money didn’t go into the gas money and insurance for the cars I needed to get to work—for the record, a ’79 Volkswagen Rabbit with electrical problems and an ’84 Ford Ranger long-bed with a conspicuously weak four-cylinder engine—would mostly be spent on movie-theater candy and arcade games, with occasional outlays to the CD of the Month club. When I got to the end of my senior year, when my part-time job had edged nearly to full-time, I had saved so little money that I called on my older sister to bankroll a senior prom excursion that never happened. (That’s another story, mostly for my therapist.)

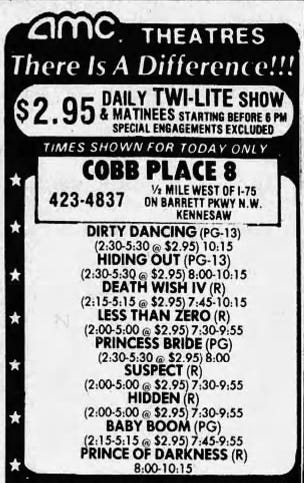

Just up the road from the Toys ‘R Us on Barrett Parkway, the busy thoroughfare running past Town Center Mall and connecting my home in Marietta to nearby Kennesaw, was AMC Cobb Place 8, a then state-of-the-art multiplex that had opened in 1986, not long after the more popular (and significantly shittier) Town Center had anchored itself just outside the mall. Back then, theaters within the same area could not overlap bookings, so a rivalry of sorts would develop between us, though Cobb Place 8 was forever on the losing end of it—partly because our booker would convince himself that movies like Bird on a Wire would be smash hits and partly because their juvenile name for us (“Cock Face 8”) was more potent than our juvenile name for them (“Clown Center”). This was before a third theater, the Cineplex Odeon (“Shittyplex Odoron”), set up shop in August 1988 with the utterly cursed line-up of Young Guns, Vibes, and Mac and Me. (Some of my most-cherished moviegoing memories were solo screenings of Love at Large and Talk Radio at the Cineplex.)

In any case, I got the job as an usher at Cobb Place 8 because I convinced the manager that I loved movies and would work hard, and I wound up making good on that promise. By the end of my time there, I’d become Chief of Staff and Head Projectionist, and would gobble up all the shifts I could to minimize my time in high school and all related social activities. I would ring in several new years mopping up behind the concession stand during closing, which sounds terribly sad in retrospect, but felt okay at the time. It would not take long for the movie theater to feel like the late-‘80s equivalent of a “safe space” for me, where I’d earned a certain amount of authority and respect, made or nurtured all my best friendships as a late teen, and was surrounded at all times by movies whirring through the projectors. And that’s to say nothing of the dulcet sounds of Lionel Richie, whose greatest hits collection dominated the theater’s five-CD changer until we snuck in records like The Church’s Starfish and Midnight Oil’s Diesel and Dust.

Our Cyber Monday Special is good for the rest of the week. First-time paid subscribers to The Reveal can now save 20% off a one-year subscription. But act fast: this offer ends on Friday.

The job of a movie-theater usher was pretty straightforward: We tore tickets during the rush times before blocks of screenings, roved the lobby and carpets to sweep up errant bits of popcorn, and cleaned up (or “broke”) the theaters as quickly as we could after they let out. The best part of the job for me was the required “inspection” run, where we’d pick up a clipboard and hang around in the back of all eight theaters for a few minutes, ostensibly making sure the films were in frame, in focus, and with the sound at a good level. I did all these things because I actually cared about the tasks, but I say “ostensibly” because sampling movies was too much of a pleasure to feel like work. Even pieces of shit could be anthropologically fascinating for five minutes—or, you know, have nudity or something—and the great films were intoxicating. (From when I was 16 through college, it never occurred to me that I could simply not see a new movie, which explains later matinee double features like Ace Ventura: Pet Detective/ My Father The Hero and Stepmom/ You’ve Got Mail.)

For me and my cohorts in the the polyester vests and clipped tuxedo ties, breaking theaters quickly became a point of pride, which now seems like a dated concept of labor—it wasn’t like AMC was paying us for the extra hustle, and they’d get a lot back from me on Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups purchases during my break—but is a work ethic that’s stubbornly clung to me regardless. Yet there were perils to taking out the trash. The demographics in the area have shifted since then—my part of Cobb County was Newt Gingrich’s district at the time, but Lucy McBath, a Black Democrat, flipped it in 2018—but Kennesaw was redneck country at the time, which for us meant small landmines of open “spit cups” waiting for us in the dark. You’d know by the warmth of the cup that the soda had been supplanted by discarded hunks of tobacco, and occasionally you’d mishandle it while attempting to zip through the rows like a garbage ninja. And when the dumpsters outside overflowed during a busy weekend, the company didn’t call in a pick-up service. Our job was to flatten cardboard boxes and act as human trash compactors, jumping up and down until we created more room in the dumpsters.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Reveal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.