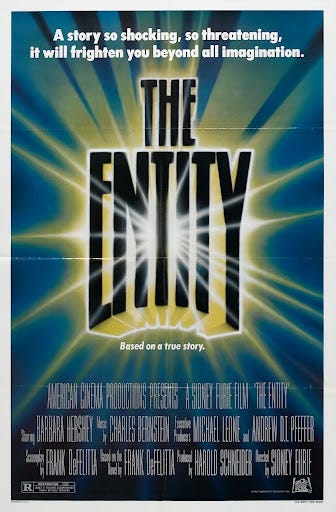

It’s October So I Watched a Horror Movie I’d Never Seen Before: ‘The Entity’

The intense 1982 film depicts the horror of a woman’s helplessness in the face of a supernatural foe—and away from it.

I’ve seen a lot of horror movies, but not as many as I’d like. so I’m going to spend the rest of this month filling in some gaps. Just a heads up: There’s no way to talk about this movie without discussing its sometimes graphic depiction of sexual assault.

“The film you have just seen is a fictionalized account of a true incident which took place in Los Angeles, California, in October 1976,” reads the closing crawl of the 1982 film The Entity. “It is considered by psychic researchers to be one of the most extraordinary cases in the history of parapsychology.” For those inclined not to believe real-life claims of supernatural phenomena, this should provoke eye rolls. And, if it didn’t arrive at the end of such a harrowing movie, it might. It’s not that The Entity, in which Barbara Hershey plays a single mother who’s repeatedly terrorized and raped by an invisible malevolent spirit, makes a credible case for being based in reality. It’s that the film’s depiction of the ordeals that follow the assault ground it in reality in ways more resonant than a strict adherence to the facts.

The facts first: For his 1978 novel of the same name, screenwriter Frank De Felitta drew on the story of Doris Bither who, in 1974, worked with parapsychologist Barry Taff, then connected to UCLA, to investigate an apparent haunting at her Culver City home. Bither’s claims included, in Taff’s terms, “spectral rape.” Though Taff did not believe these to be true, he found other evidence of supernatural activity in the Bither home and was able to photograph some strange lights. In a Skeptical Inquirer article, paranormal investigator Benjamin Radford casts a, well, skeptical eye on the incident. Bither’s story is, from what details can be confirmed, more sad than scary and the photographs don’t stand up to scrutiny.

Best known as the author and screenwriter of Audrey Rose (which he claimed was grounded in his own supernatural experiences with his son), De Felitta was no stranger to stories of the paranormal. For his version of Bither's story, he took only what he needed, reshaping her into Carla Moran (Hershey), an executive assistant for an unnamed L.A. company who takes typing classes at night and does the best she can raising her goodhearted, meatheaded teenage son Billy (David Labiosa) and two young daughters, Julie (Natasha Ryan) and Kim (Melanie Gaffin). After a typically exhausting day, she returns home to a sink full of dirty dishes and no messages from her absent boyfriend Jerry (Alex Rocco). Then, while preparing for bed, she’s struck across the face, thrown onto her mattress, and sexually assaulted.

The audience receives just as little warning as Carla and the scene plays out quickly and violently, mostly via shots of Carla’s face as she’s held down beneath a pillow and the rattling of a bedside lamp as Charles Bernstein’s score takes an abrasive turn. The scene is shocking for both its brutal content and its swiftness. When she wakes her family with her screams, Billy tries to tell her she must have had a bad dream. It’s the first of many instances in which men will try to impose a narrative explaining away what’s happened to Carla rather than confront it.

When Carla senses the entity has returned, she flees with her family to the house of her lifelong friend Cindy (Margaret Blye), then returns home when Cindy’s husband objects to their presence. After the being forces her to crash her car, Carla takes Cindy’s advice and visits a psychiatric hospital, where she meets Dr. Sneiderman (Ron Silver), who does his best to explain what’s happened via science. He’s sympathetic but insistent. Even after a second assault leaves physical evidence, he probes into her past, which includes an incestuous father, teenage motherhood, a dead boyfriend, another boyfriend who left without warning, and Jerry, who seems to love her but who’s never around.

Victimhood has made her past an open book and though Dr. Sneiderman seems to be on her side, a subsequent meeting with his superiors and peers at the hospital feels like a tribunal. With a filmography that includes everything from the espionage classic The Ipcress File to Iron Eagle to Ladybugs, Canadian director Sidney J. Furie defines the term “journeyman.” Understanding what he has to do, he creates unease with canted angles and plays Carla’s encounters with her invisible enemy with horror movie intensity. But he also brings a care and understatement to scenes like these. Sitting at a table surrounded by doctors—mostly men—in white, Carla wears a blue dress as she has to field their questions. Why, one asks, does he attack her and not anyone else? But the most unsettling question comes from one of the few women at the table: “Would it be a reflection on you as a woman if he left you? Or if you were cured?” When she leaves the room, any sensitivity leaves with her. Most of the table lights up cigarettes or pipes and the psychiatric chief lays out his conclusion: “She’s masturbating. This entire circus she’s invented to cover up what every little girl does.”

Up to this point, The Entity has carefully staged its action in ways that invite the skepticism of other characters. Viewers never have any doubt that Carla’s being attacked, but it’s easy to see how others can look at the situation and draw other conclusions. (This is also more or less the template for every episode of The X-Files and Evil.) Even when the entity hurts Billy’s wrist as he attempts to fend Billy off while attacking Carla in her living room in the presence of her children—a scene that’s just as disturbing as it sounds—it could be read by outsiders as a kind folie à deux, with Carla acting out the assault and Billy playing along without realizing it.

But it’s a different sort of tension that makes the film resonant. Carla’s attempts to be heard and believed and the system lined up against her and seemingly designed to silence her maps onto the experience women who’ve been victims of the more familiar sort of sexual assault. She doesn’t call the police because what would they do? When she does seek help, she’s essentially told it’s all in her head and whatever happened had to be because she wanted it to happen, even if she can’t admit to her shameful desires. (That the entity takes up residence in her house expands the real-world reflections to a relationship with an abusive partner.)

Though a minor theatrical hit, The Entity hasn’t always been the easiest film to track down. Arriving in North America in early 1983, months after its 1982 release in the UK, it appeared on VHS the same year and has been in and out of print since first appearing on DVD in the mid-‘00s. If you first encountered it, as I did, on the Criterion Channel (the only service currently carrying it) as part of its Horror F/X collection, you might spend half the movie wondering why it’s been included as, up to a point, the film contains little in the way of any special effects.

That changes in the second half, with a pair of scenes that depict two subsequent attacks. In the first, Carla awakes in shame and horror after being stimulated to orgasm by her assailant in her sleep. In the second, the returning Jerry walks into a room in which Carla has been pinned nude to the bed. In both, we watch as Carla’s skin—actually a dummy covered in latex—ripples as the entity’s fingers move across it. Both scenes are extremely disturbing, no less so for the effect—the work of Stan Winston’s team—not quite being entirely convincing. Carla’s been made an object for her victimizer to do with as it pleases. (To its credit, the film never treats its material luridly, with the possible exception of a couple of shots of Hershey’s (non-latex) nude body double.)

No effect would make the film work if Furie, De Felitta and, most importantly, Hershey, didn’t take it seriously. Hershey plays Carla as a grounded, perfectly ordinary woman dragged into a hellish existence because she drew the attention of the wrong malevolent being. She puts her trust in those who question her sanity, even making her doubt it. Hershey’s never better than in the scene when Cindy witnesses the end of one attack that trashes her apartment and refuses her husband’s suggestion that Carla did the damage herself. “You saw it?,” Carla says with relief. She may not know how to end what’s happening to her, but at least someone else can bear witness.

The Entity goes big in its final act, in which some parapsychologists from UCLA build an elaborate trap in which to snare the entity involving a full-sized model of Carla’s house and a big tank of liquid helium. It’s a little silly but effective anyway and though the climax puts the emphasis on spectacle rather than scares, it keeps the metaphor afloat when Carla is told, with mounting urgency, to get to “Move to the protected area,” a spot carved out to keep the entity away, only to find that it’s hard to reach and offers no real protection once she arrives. Then, after being rescued, she discovers that rescue and escape aren’t quite the same thing. In the final scene, Carla prepares to leave her home only to sense the entity once again. She’s able to slip away, but the final lines of the closing crawl offer a downbeat summary of what happened next to the “real” Carla and, it’s safe to conclude, the Carla of the film: “The real Carla Moran is today living in Texas with her children. The attacks, though decreased in both frequency and intensity… continue.” Some ghosts never vanish. They just, with luck and time, diminish.

Nice work, Keith. To me, the most harrowing - and thematically on-point - moment is when Carla says, in so many words, that's she's just going to live with it and placate the entity. It's crushingly sad.

One of the few great paranormal horror films. Partly because even if it was all in her head the dismissal and victim blaming would still be terrible,. The entity would still be something out of her control, which I think is what leads to paranormal explanations in the real world: because it's so hard otherwise to express that it's not the sufferers' fault.