Interview: Matt Singer on 'Opposable Thumbs,' his new book about Siskel and Ebert

Our former Dissolve colleague discusses the unlikely rise of two newspaper critics who became influential television icons.

When The Dissolve first came together a decade ago, it was a vessel that functioned a bit like a lifeboat, staffed almost entirely by long-time A.V. Club writers and editors who were looking for a fresh start somewhere else. The one exception was news editor and chief Gymkata admirer Matt Singer, whose sensibility and voice we had admired when he worked on-air and on-the-page for IFC, and when he served as the founding editor of the erstwhile Indiewire film criticism blog Criticwire. Singer has spent the last nine years as the managing editor and critic of ScreenCrush.com and for many years co-hosted the Filmspotting: Streaming Video Unit podcast with Alison Willmore. He also wrote the gorgeous 2019 art book Marvel’s Spider-Man: From Amazing to Spectacular: The Definitive Comic Art Collection.

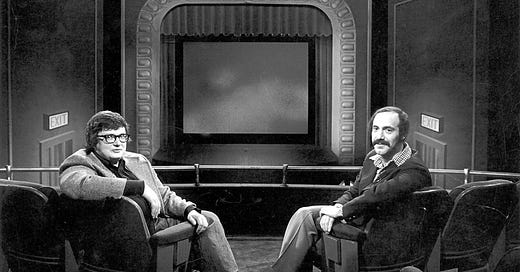

There’s simply no one better-suited to write about Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert’s adventures in television than Matt. His new book, Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever, springs from his own history as a film writer, from his obsession with Siskel & Ebert as an adolescent growing up in New Jersey to his appearances much later hosting segments for Ebert Presents, one of the review shows that Ebert supported after he’d lost his voice to cancer. Opposable Thumbs digs into Siskel and Ebert’s humble, often hilarious beginnings at the Chicago PBS affiliate WTTW, where they started a film review show in 1975 (originally called Opening Soon… at a Theater Near You before being renamed Sneak Previews) as bitter crosstown newspaper rivals. Their personal frostiness would thaw over the years, however, as they expanded into a wildly popular duo in syndication—first at Tribune Entertainment (as At the Movies with Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert) and later at Disney (first as Siskel & Ebert & the Movies, then simply At the Movies).

Opposable Thumbs goes behind-the-scenes with many of the people responsible for the show in its numerous incarnations, and shares a wealth of stories about various dust-ups, pranks, and experimental gimmicks. Matt also pored over the episodes themselves—every single one!—to get a sense of their evolving chemistry and the arguments that made them so influential as tastemakers and unlikely pop icons. He talked to us about his origins as a Siskel & Ebert superfan, how the show acted as a time capsule, the ways it dramatically altered film culture, and the handful of episodes in which a lethargic skunk was brought in for the “Stinker of the Week.”

The book comes out next Tuesday, October 24th, but is available to preorder now.

When did you start watching Siskel and Ebert? What is your first memory of watching that show?

I don’t have a first memory. This is the thing I’ve realized doing these interviews. I should have an amazing first like, “I was watching late at night. I was flipping the dial and I said, "By Jove, who are these two chaps in sweaters?," or something. The weird part of it is that I don't remember the first time I watched the show. All I remember is that, by a certain age, which would be like 12 or 13, I just irrationally loved the show and was obsessed with it. I was not even a super movie nerd at the time. I liked movies, obviously. I went to the movies a lot. I was like Siskel and Ebert were as kids: I liked movies, but it wasn’t like they defined my existence. I was much more into comic books at that age.

This is the question that I still have not solved, “How did I find them and why did I become so interested?” Maybe, in some ways, the book is the answer. I was just kind of fascinated by these two guys. They didn’t look like the other people on television. They didn’t really talk like the other people on television. They had these great arguments and discussions and conversations about movies.

I think it hit me at the right time, the right age, where I was just starting to get interested in movies. They were like my first film teachers, in a sense. They were the ones saying, “This is the old movie you should go to your video store and rent. This is the movie that, if by some chance you can convince someone to drive you to an art house theater a half an hour away, in the college town nearby, this is the movie you should go to see,” or that sort of thing. So, yeah. I don’t have a great, juicy, first time story. At that age, it was like it became this fact of my life and this total obsession of mine.

Do you remember any movies, or filmmakers, that the show introduced you to?

In the summer of '96, when I was 15, I took a trip to Rhode Island. I was in Providence, which is not the biggest metropolis in the United States, but it has better movie theaters than suburban New Jersey where I grew up. So the whole time I was there, I would walk past a movie theater and say, “Oh, this place is showing Trainspotting. I heard about that on Siskel and Ebert.” If I had waited, I might’ve been able to see it on home video. There was no chance I would ever see it before that. It happened to be playing. I didn’t know much about it beyond their review,it looking really good, and their comments about it.

It became one of those formative movie going experiences. To this day, I don’t know how I got in. Maybe I was with people that were older and they sort of allowed it. I was 15, but I must’ve looked like I was 11. Puberty had barely even hit. I looked like an infant. There’s no way I could pass for a 17-year-old. So, God only knows how I got in. I just remember being in that theater, in the second to last row. It was packed and just the energy. It’s like a mind-boggling experience.

Then on that same trip, I also saw Lone Star, the John Sayles movie, which was another movie that they had really strongly recommended. I even remember it was at the Cable Car Cinema. That whole place blew my mind. They didn’t have theater seats. They had reclaimed, ancient couches. To a 15-year-old, this is like, “I’m in the coolest place on earth, right now. They’re showing this John Sayles movie, and I’m lounging on a couch to watch it. What could be better than this?” The vibe in there was a little different than the Trainspotting one, but again, I had a great time. I loved the movie. For sure, those were the sorts of movies that I never would’ve watched otherwise at that age, if not for that show.

What was it that sort of compelled you to write this book? What were you kind of seeking out in putting this book together?

There’s a few different reasons that are kind of interrelated. My wife was the one who really pushed me to do it, when I was looking for another book topic, after I had written one book about Spider-Man—as I said, my first love. I got to check that off the list and I was very happy with that. Then I wrote a second book that has never seen the light of day, unfortunately, to this point. Hopefully, someday it will. After that, I was determined that if I was going to write another book, it was going to be something that I had more control over and I was more in the driver’s seat. So as I was doing that, working on ideas, I was putting together a list of potential ideas and I showed it to my wife Melissa.

When she saw it, her reaction was, “Yeah. These are fine. Some of these are good, but why isn’t Siskel and Ebert on here?” She knew that I was such a huge fan of the show and knew a fair amount about it, and would be qualified to write about it. I told her that I was intimidated by it. Just the thought of writing something about writers, especially writers I admire, that were influential on me, seemed to invite comparisons I was terrified of.

That was a big part of it. Her response was, “Get over yourself. You’re being weird. If anyone else writes this book, you will be so angry that you didn’t do it.” As usual, she was 100% right—hopefully on the first count, definitely on the second count. I would be angry. So it wound up on the list. Then working with my literary agent, he was like, “Yes. This is the one.”

How did you set about writing this book? Where did you start?

In the later years of the show, after Roger had lost the ability to speak and wasn’t doing the show anymore, I auditioned for it. Obviously, I wasn’t the host of any of those shows, but I wound up getting roles as contributors on the different versions of them. So I got to meet a few of the people who worked behind the scenes. Because I was such a huge fan, for no other reason than I just wanted to know, I would be like, “Tell me some stories. I’ve got to know some stories.” Generally speaking, the people who were involved with the show kind of loved telling these stories because they're great stories. So I reached back out to some of those people and said, “I’m thinking of doing this. Would you talk to me?” Thankfully, pretty much everyone said, “Sure.” So, that was the first part.

Then the next part was using them to broaden the scope and introduce myself to people I didn’t know and speak to them. Then there was a lot of watching and re-watching, hours and hours. I have multiple documents on my laptop, tens and hundreds of thousands of words of notes just about episodes. I would write down the reviews, what they reviewed, what the votes were, what they wore. I have so many notes about their sweater vests and their jackets and their blazers. I never used any of it. I didn’t know what I was going to use, so I would take really close notes. I would write down movies that they loved and movies that they disliked and movies that they fought about. Just building up this kind of massive list of stuff that I could draw on, just to see, without knowing, what would come of it. Then, eventually when I got to writing, it was a matter of finding what was useful. A lot of it was very useful. Then some of it ended up not being. Unfortunately, I never found a place to write about their sweaters and their clothes.

How grueling of an experience was it to go through that much footage? That’s a lot of episodes.

To someone who doesn’t like the show, it would have been quite grueling. That's a good word for it. We’re talking about hundreds of episodes and hundreds of hours. But you’re talking to mega-dope fan number one. So to me, it was fantastic. I thoroughly enjoyed so much of it. Honestly, I really did. It was a pleasure. The way I was doing it, most days, I’m working my day job. The kids come home from school. We have dinner. We hang out. They go to bed. My wife, who’s a schoolteacher, usually goes to bed pretty early. Then I would just kind of hunker down and watch two or three hours of Siskel and Ebert, every single night.

The thing about the show, at least to me, is it’s a fascinating document. It really is this incredible kind of repository of film knowledge from that time period. You can learn a lot about the film world from 1975 to 1999 by watching this show. You put on any random episode, you’re going to get a sense of what was new in theaters, what issues people were talking about at the time, what was out on home video, who’s in the news. Sometimes there’s interviews or commentary. It doesn’t feel like that long ago to me because I was alive for almost all of it. But you see how differently the movie world is now, compared to then. It really was endlessly fascinating. That’s on top of the fact that they’re just fun to watch. They’re fighting and debating and arguing. Honestly, if someone reads the book and they're interested, just go watch some episodes. You might be surprised how quickly you can fall down that YouTube rabbit hole, in quite a pleasant way.

I did a little bit myself. One thing that stood out for me, just watching random episodes, is there would always be one or two films an episode that would have pretty big stars in them and you're like, “This movie doesn’t exist anymore.” I mean, you can find it on the IMDb or whatever, but it is just gone from the discourse. It's incredible to see how even a studio film, with stars, could just disappear.

The book that people will read is pretty close to what I pitched originally. I had to make a proposal and lay out all the chapters. The finished book is very close to what I originally envisioned, with one exception. The back of the book is this appendix of the buried treasures that Siskel and Ebert loved. That just happened because, like I said, I was watching all these episodes and like you I’m going, “Wait. What movie is this? Who is in this, and how have I never even heard of this movie?” In some cases, they're giving them two thumbs up and saying, "This is a wonderful movie and everyone should see it.” You’re going, “Well, somehow this movie has just kind of fallen through the cracks of time.”

Do you have a favorite exchange? There are some famous dust-ups that have gotten a lot of play on YouTube, but is there anything, when you were going back and watching all of those episodes, any particular exchange that’s kind of a gem for you?

The one that I write about in the book is probably my favorite, a whole debate about these two movies, that to your point barely exist at all anymore, Stella and Men Don't Leave, these two random melodramas. I watched them for the book. To me, neither one was especially memorable. I loved the fact that these were such similar movies, in terms of their subject matter and their genre. But Gene and Roger had two totally different reactions to them. One loved one, the other loved the other. They reviewed them on the same show, so their reactions got to live next to one another. One built off the other. By this point, they would do their best to record everything in one take, if possible, and get their immediate, honest, genuine reactions. That made the conversations more authentic. That was how the show worked best when they did it.

I don’t know if it was intended or not but it became an excellent aspect of the show. Doing things that way didn’t allow them to calm down after a review got heated, which meant if another review on the same show was also heated, it got more heated. They were still pissed off from the last time they talked! So, those are the best episodes. One disagreement on an episode can be great. When you get an episode where they disagree a lot and they’re just getting angrier and angrier, that’s where the vibes get really enjoyable. In this case, that’s one of those examples where they’re already kind of angry at each other. Stella came first. They have this huge fight. Ebert liked it. Siskel hated it. Ebert is saying, “Well, I could hear people sniffling in the theater, they were so emotional.” Gene is like, “You know? There's a lot of flu going around, right now. Maybe that was the reason.” So, they’re already kind of at each other. Then two movies later, they get to Men Don’t Leave. Now Siskel is the one who’s very enthusiastic. Ebert is all pissed off.

It’s almost like they’re not, even at that point, debating the movies. They’re debating watching movies and asking “What makes a good movie? Why are two movies about the same thing so different? Why are we, two people who saw both of them, having such wildly dissimilar reactions?” So it’s fun if you like movies. It’s also fun if you like thinking and writing about movies, and thinking about what makes them good and bad. It’s just a great way to examine the critical perspective and the critical mindset because they saw things from such different perspectives sometimes. Then they made that the focus of the reviews, which became very entertaining and interesting to watch.

When you started going through the archives, could you see a point at which these guys started to get more comfortable in front of the camera? Do you see the evolution of them as TV performers?

Oh, for sure. They got pretty good within a few years. Still, it’s amazing just to think you would have that much runway. If they were on now, no one would have a few years to get good at it. You know what I mean? Years later, when Ben Lyons and Ben Mankiewicz and Michael Phillips and A. O. Scott are coming in, they’re getting judged on their very first episode. They’re getting dismissed out of hand, immediately. If Gene and Roger had been given that same treatment, the show would not have lasted long enough for them to get as good as they got. It did take them a year or two to really get the hang of it. By the end of their run on PBS, which is the early ’80s, they’re a pretty well-oiled TV machine at that point. They know what they’re doing. They’re good at what they do.

It kind of shows in just the fact that that’s right around when people start paying attention elsewhere in television. That’s when Letterman’s bringing them in. That’s where they first start showing up on talk shows. It’s by that point where they are “Siskel and Ebert” in air quotes. But the magic was not instantaneous. This was not love at first sight. It took a while.

The section of the book that deals with a lot of this trial and error stuff is just so fascinating. Like when the “Dog of the Week” became a skunk. They had a live skunk! How in the world did that happen? How many episodes did the skunk appear on?

The skunk is not in that many episodes. He was the replacement. The “Dog of the Week” was a facet for years and was on lots and lots of episodes. They had multiple dogs. Dogs would vanish and they would have a new dog. Some of the stories were pretty bleak, actually, about the dogs. When they left PBS, which was their original home and started their first syndicated show at Tribune, it was determined by lawyers that they were legally allowed to talk about movies. They couldn’t get sued for just doing another show like the old show, but certain aspects were deemed potentially copyrightable. They could perhaps get into trouble if they just replicated specific segments. Dog of the Week, where they would review a bad movie with their dog sidekick, was deemed problematic.

So their solution was to do the “Stinker of the Week” and have a skunk instead of a dog. The problem was that skunks... It might surprise you to learn that skunks are not exactly friendly, social animals like dogs are. I guess you can get a “trained skunk” or a domesticated, de-scented skunk to have on your show, but the skunk is not going to play ball. He’s not going to fetch. He’s not going to jump in his seat.

The problem was the skunk would just kind of lay there. It almost looked like it was dead sometimes. You watch the episodes with the skunk, and the skunk is just sprawled out. They’re trying to pet the skunk and get anything out of the skunk. It’s just not a very cooperative animal. It might only be as few as ten episodes or something. Then the skunk goes away. One great story that they told at a banquet is that when they said, “We’re not doing the skunk. It’s just not working,” the producer didn’t want to give up the whole idea. So he was supposedly like, “I got it, guys. We’ll do the Turkey of the Week." They're like, “You're really going to put us on a set with a turkey?” He’s like, “No. A turkey vulture.” I mean, that’s incredible. You just can’t make this stuff up.

Siskel and Ebert were attacked quite a bit at the time for being bad for criticism and reducing film discussions to sort of that thumbs-up/thumbs-down declaration. How did those criticisms of the show look, in hindsight?

Some people got very upset about this show. There is a part in the book where I detail one of the more famous back-and-forths about whether the show was ruinous to the state of film criticism or not. Obviously, I come at it from a somewhat biased perspective in that I would not be doing what I do without the show. The show was the thing that got me interested, in the first place, in film and film criticism. So I’ve never really subscribed to any aspect of that argument. It does seem that a lot of people of my age feel very similarly and that this show really had a great positive effect on them and on their love of movies, their love of film criticism. It really was the perfect introduction to all of that stuff. It’s very hard to say that this had a negative impact, in my perspective.

Michael Phillips told me a story about guys he knew who worked in a factory. He would say, “Well, why did you go see this arthouse movie?” They were like, “Yeah. Gene and Roger told us to go see it. If they’re talking about it, it must be pretty good.” That was a common thing. It’s like that show drove people to see movies.

Now were the reviews short? Yes. The reviews certainly were shorter than the reviews you’'e going to get in Film Comment, where these arguments were being made at the time. Film Comment is a fabulous magazine, which I never would’ve read in my entire life if not for Siskel and Ebert.

I think that it’s important to separate the show and how Siskel and Ebert were used by the studios to market their movies. If you only knew Siskel and Ebert from the phrase “Two Thumbs Up,” okay. But if you watch the show, even those shorter reviews, like the ones we were talking about before with Stella and Men Don’t Leave, even those could get into more interesting topics than just, “Is this a good or a bad movie?”

Their reviews sometimes got into discussions of politics, religion, philosophy. That doesn’t even consider all of the episodes where they would set aside the main format and spend a half an hour proselytizing about black-and-white films, or the dangers of colorization, or a survey of recent independent cinema, or talking about the movies of Spike Lee or Quentin Tarantino. The show was more than thumbs. Clearly, I think, in hindsight we can all see that. With all due respect to the people complaining, some of whom are other critics that I respect and admire, I feel like the show did a whole lot of good for a whole lot of people in the world of movies. It is interesting to look back on those arguments now, about how “They’ve ruined film criticism.” What would those same people have thought about, I don’t know, Letterboxd, or people on social media posting 150 character reviews? Not even words, now. We’re down to characters. We’re numbering the characters in dozens, not the words.

The idea of a movie review show sort of sputtered after Siskel and Ebert’s partnership ended. You obviously had different iterations of the show or other film criticism shows. Was it the strength of their chemistry that was so hard to reproduce or was it more about movie review shows not really having a place in modern television?

That’s a question that I thought a lot about during the book. I feel like the answer may be both, or all of the above, in a certain sense. I do think that they were so good at what they did, and became so synonymous with it, that it became impossible for anyone else to measure up. Even Roger had trouble doing it with Richard Roeper. It did well enough in the ratings and it wasn’t a bad show, but the common complaint was, “Well, it’s not Siskel and Ebert.” That was the knock on it. You read Entertainment Weekly’s review of Ebert and Roeper. They’re complaining that Richard Roeper looks like he spends too much time in the gym, or something like that. It’s a little surreal that those were the complaints. But It does also seem like the TV landscape shifted. I mean, they were on for 25-ish years, so of course things were going to change.

When they started, especially when they moved into syndication, it was a perfect show for syndication because you could play it anytime, theoretically, on the dial. It didn’t cost a lot of money to make, just two guys sitting in a movie theater talking about movies. That’s kind of universal. But on the other hand, then syndication later became such a money driver. It was all about shows that could be syndicated and shown five times a week and be an hour long. It became kind of small potatoes to these companies, in a sense. That idea that drove the show—minus the movies, just the idea of people debating and discussing—became co-opted by so many other things. It would be tough to do Siskel and Ebert five times a week. What are you going to talk about? They would’ve struggled to fill all that time.

You can do that show for sports, very easily. Every day, you’ve got a new game or a new controversy or a new player or whatever, and you have all the different sports. The format is so easily replicable to that or to politics. I do think that at a certain point, it was like the movies were kind of specialized and tough to scale up. Whereas you could take this basic format and do it in these other areas that you can really scale them up. It feels like some channels are now nothing but this format, almost 24/7.

Could you talk about your own interactions with Ebert while he was still with us? You did not know him prior to him losing his voice? When did you all first meet?

I met him, one time, at a book signing that he did in New York, in 2005, just as a fan who attended and got a copy of The Great Movies II, still signed over there. So, yeah. I didn’t interact with him in any real sense, other than doing the Chris Farley Show bit of, “Remember when you hosted Siskel and Ebert? That was really cool.” Until working on that final version of Ebert Presents.

Honestly, it was incredibly thrilling and exciting. I mean, no question. He was someone I looked up to as much as anybody in my entire life. I can’t say I ever thought I would realistically host Siskel and Ebert because their names were in the title. So just the fact that at various points I got to work on the shows was amazing. Then to work with him was just really incredible. Face to face, we didn’t have a ton of interactions because the show was in Chicago and I was here. I would exchange emails with him. When I was working on the segments that I would do for the show, he would be sending me notes and feedback and comments.

One time I submitted one of my scripts. I did three segments for that show. He wrote me back a note. The subject was, “You are just.” The email said, “Plain good.” I remember just sitting and staring at it for an hour. It was just like the best email I ever got in my life, and it’s six words. That’s it. If I had been drummed out of film criticism forever after that moment, it would’ve been worth it. You know what I mean? That’s about as good as it’s going to get for a guy like me.

A lot of people have had that experience, not just me. He was very giving to that kind of up-and-coming generation of film writers around that time. He would spotlight them on his website and tweet out links to their articles when he liked them. At the time, he was one of the biggest users on Twitter. He had hundreds of thousands of followers when that was not common. He liked encouraging young, talented people and kind of spotlighting them.

My last question is how quickly did you arrive at the title Opposable Thumbs? Was that just like a eureka moment or do you actually have to mull it over?

When I came up with it, it definitely was a pencils-down kind of moment. It wasn’t the first thing I thought of. I still have a list of all the ideas that I had while I was working on the original proposal for the book. I would sometimes just sit and think about different ideas. Some were a little too obvious, too on the nose with the thumbs. But the thumbs seemed like they had to be in there. Okay, that document is on my computer, which I do have right here in front of me. Let’s see.

I'll give you a bunch of them. I mean, I have Best Enemies, which was the name of the sitcom that was pitched to them. Chaz Ebert told me about that. Somebody wanted to make a sitcom of Siskel and Ebert, and that was the title, Best Enemies. I have The National Dream Beat. That’s what Siskel called his job as a movie critic, “Covering the National Dream Beat.” That’s a lovely phrase, but it’s not quite the same as Opposable Thumbs. I have Thumb Wars, which I thought, “That’s not bad.” I have 15 titles written down, and the last one is Opposable Thumbs. I got to that and that was it. No more thought required. That was the winner.

I love Matt's comments about how the most important thing these guys did was just get people talking about movies. There was an episode from 1990 that I still remember because

1) They reviewed TREMORS, which got a split decision but which made my dad laugh hard enough that we went to see it that very afternoon.

2) The did an extended piece on aspect ratios that blew my mind. For the first time I learned that what we were seeing on VHS was not the whole picture. They clearly and articulately explained the issue of cropping and pan & scan and why directors choose to compose certain shots certain ways with clips from then-current LAST CRUSADE and my 14-year old brain just ate it up. Changed the way I looked at movies.

That's a shame that some critics level the reductive claim on Siskel and Ebert. They were the gateway drugs to films and film criticism; I can't even imagine a world that didn't have these two guys talking about movies.

I can still remember watching Siskel's final full year on the job, choosing Babe 2 as his best movie of the year. ❤️

What a great interview, and what a great book. I see Matt read the audiobook himself, perfect! That'll be my copy.