Interview: John Sayles on 'Lone Star'

The legendary independent filmmaker talks about his acclaimed 1996 drama about a decades-old murder mystery in a Texas border town, now in the Criterion Collection.

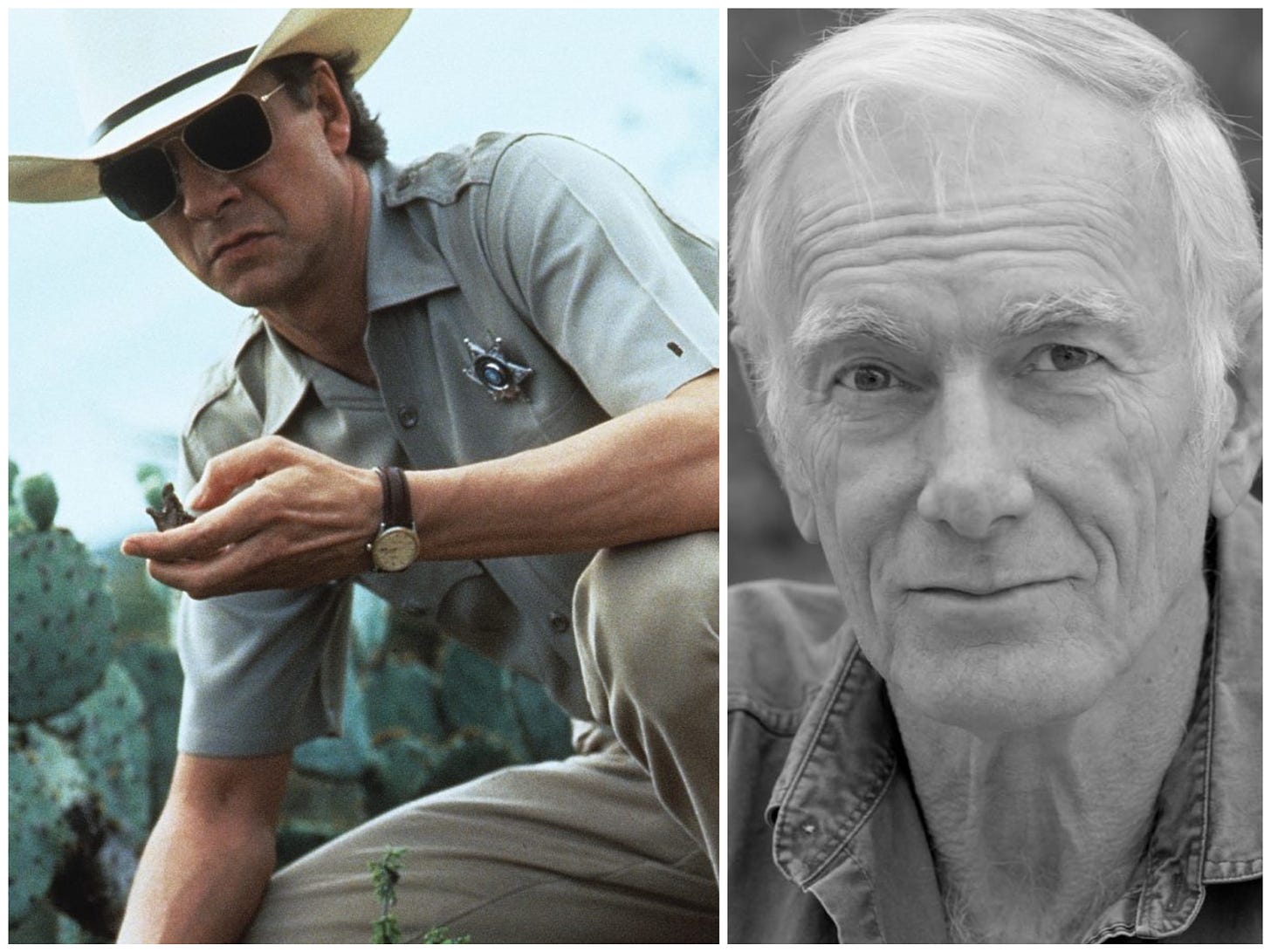

Like many significant directors of his generation, John Sayles cut his teeth working for Roger Corman, for whom he wrote one of his two high-quality Jaws knock-offs, 1978’s Piranha (1980’s Alligator is the other), while nursing his own ambitions as an independent filmmaker. With the money he’d scraped together on these screenwriting jobs, Sayles parlayed a minuscule budget (estimated at $60,000) into a debut hit with Return of the Secaucus 7, an ensemble piece about a weekend reunion among old friends that established his talent for sensitive, character-driven stories with sociopolitical underpinnings. Well before the independent scene blew up in the late ‘80s, Sayles continued to turn out acclaimed work on a relative shoestring, including 1983’s Lianna and Baby It’s You, 1984’s The Brother from Another Planet, and 1987’s Matewan before Orion bankrolled his accomplished 1988 sports drama Eight Men Out, about the Chicago Black Sox scandal of 1919.Sayles’ interest in exploring the complexities of American history and myth making was evident in Matewan and Eight Men Out, and his 1991 urban tapestry City of Hope broadened his scope to larger communities and how they intersect. Sayles would direct two small-scale pieces after City of Hope—the 1992 Bayou drama Passion Fish and the 1994 Irish folktale The Secret of Roan Inish—but his storytelling ambition turned more expansive than ever with 1996’s Lone Star, arguably the biggest commercial and critical success of his career, earning him his second (after Passion Fish) Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay.

Joining the Criterion Collection next week, Lone Star opens with the discovery of a skeleton and a sheriff’s badge on a dusty rifle range in the Texas border town of Frontera. The investigation turns personal for the town’s current sheriff, Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper), who owes the position to the popularity of his late father Buddy (played in flashbacks by Matthew McConaughey), whose own celebrated tenure has led to a controversial measure to rename the local courthouse after him. Sam’s feelings about his father are ambivalent, to put it mildly, and they grow more complicated still when Buddy’s actions in the past start to figure into the case, which drums up ugly incidents around a racist sheriff (Kris Kristofferson) and the power he wielded over Black and Mexican-American businesses as well as border issues. Meanwhile, Sam reunites with his old high school flame Pilar (Elizabeth Peña), a widowed teacher whose mother Mercedes (Miriam Colón) interfered in their relationship when they were teenagers. Joe Morton rounds out the cast as a newly commander at the local army base, which brings him back into contact with his long-estranged father (Ron Canada), who also figures into the larger story.

Sayles’ novelistic approach to Lone Star would surface again in later films like 1999’s Limbo, 2002’s Sunshine State, and 2004’s Silver City, to say nothing of the actual novels he’s been writing since before his filmmaking career began. The latest, Jamie MacGillivray: The Renegade's Journey, published by Melville House, follows a pair of 18th century characters of diverse backgrounds from Scotland and England to the American Colonies. His other credits as writer-director include 1997’s Men with Guns, 1999’s Limbo, 2003’s Casa de los Babys, 2007’s Honeydripper, and 2013’s Go For Sisters. At home on a press day for Lone Star, he talked to The Reveal about the recurring nature of border conflicts, his Raymond Chandler-inspired approach to genre storytelling, and the practical benefits of casting the right actors for the job.

I was watching an old interview that you did for this film, and was surprised to see you mention what was happening at the time in Yugoslavia as being something that was on your mind when you were making the film. Why was that? Why did that enter your mind when you were thinking about border issues?

Part of my idea to do a story set on the border came from a trip I took to see The Alamo in San Antonio. The day that I went there, there was a protest march around the Alamo of Mexican-Americans saying, “How come you don’t tell the whole story?” There were Mexicans inside the Alamo who just didn’t like Santa Ana and they never get mentioned. And one of the main freedoms that the Texans were fighting for was the freedom to own slaves. That was very important in their decision to risk their lives, to tear this territory they had been invited to live in away from another country.

And so I started thinking about what I was taught and what I learned watching Walt Disney, the legend of Davy Crockett, and the John Wayne version of The Alamo. When I went in and read what actually happened, it was very different. So why don’t most Americans know that different version? Well, that’s a choice, and some of it is who’s controlling the history, but some of it is, “What do we want to think about ourselves?”

So I started thinking about seeing these interviews with people who were saying why they were ethnic-cleansing the Serbs or the Croats or the Herzegovinians or whoever they didn’t like. Very often it would be, “Well, back in the 13th century, they stole our land,” or “They slaughtered a bunch of us.”

I said, “The 13th century? That’s what you're fighting about, really? This story—and history is a story—you’ve been holding this in your heart through all those generations, and you want to murder people because of that?” Or “You think this land is only yours because of that?” It could have been the Middle East, too, like what’s going on now between the Israelis and the Palestinians.

Legends are stories we tell about ourselves and we tell them to say, “This is who we are. This is why we feel good about ourselves. This is something we can be proud of.” What happens when they are more destructive than useful? What do we do with them? And we’re still fighting.

That scene in the school [in Lone Star], where the parents are fighting with the teachers and the principal, could happen tomorrow in Texas or a bunch of other states. And now state governments are getting in and mandating, “No, you can’t teach what actually happened or you’ll lose your job.” So [Yugoslavia] was what was happening at the moment. That was the most like the story that I was telling. What do we do with these legends when they’re getting us into terrible wars instead of making our lives better?

So it’s evergreen. If you make this film now, you’re thinking about a certain set of conflicts that are happening that are parallel to what happens in the film.

We were just at the Belfast Film Festival, and they’re not shooting each other in Belfast anymore, but they are not living together, either. They’ve actually moved geographically a little further apart. So if you’re a high school kid and you’re Catholic, you’re not going to meet a Protestant kid until you maybe go to college, if you get to go to college. That’s what they’ve done.

But that’s an old story. It is not as old as the 13th century, but it’s pretty damn old. And people were being murdered every day for a long, long time. While we shot The Secret of Roan Inish there, there were British soldiers with sniper scopes following us as we drove through towns. So these things, they can be fatal, these stories.

Did you ever see a documentary that was made seven years ago or so called Western? [Western, the Ross brothers documentary from 2015, takes place in the border town of Eagle Pass, where much of Lone Star was shot. The film is about the collegial relationship between towns across the U.S.-Mexican border, which is subject to outside political pressure. —ed]

Yeah, I did see it. It’s good. I think one of the guys at least had gone to NYU Film School and one of my former collaborators, John Tintori, was running the school at that time and he told me to look out for it. And things have not gotten better [in Eagle Pass] since then.

They had two very good mayors at that time [in Eagle Pass and in Piedras Negras, Mexico] who were really trying to cooperate, but then this wall got put between them. Then [the Piedras Negras mayor] died in a plane crash and now there’s a lot of tension there. Plus, and this is the one part of Lone Star that makes it a period piece, the narco traffic has moved down the border from Laredo and El Paso to all of those towns. So the Border Patrol guys have to wear body armor now. I couldn’t leave that out of the story if I made the movie today.

What’s interesting about Western and Lone Star is that you have this border town where the relationship between people across the border is much more complicated and nuanced and often collaborative.

When we were in any of those border towns, one of the things you realize is the majority of the people speak Spanish at home on the Anglo side as well as the Mexican side. They have cousins and friends on the other side. The governments are the people who are separating them. Now, there’s also this traffic of people who aren’t from that Mexican town who are coming through. They may not even be Mexican. They may be from Central America or wherever. But the symbol of the wall has gotten so important to certain people in politics and certain voters who support those people that it means more, and it's allowed to stand between these people who actually would be pretty happy to just co-exist.

While we were there, you could put a dime in a slot and walk through a turnstile and then go have a margarita in Mexico. Or do the opposite and go to Walmart, and then two hours later, back over. That’s how porous the wall was in those days. I played a Border Patrol guy in the movie, and I ended up cutting those scenes out. Not that they were bad, but I just didn’t need them. But I got to talk to the Border Patrol guys and they said, “The phrase we say the most is, ‘Don’t make me run.’” People would walk over. They checked to see if they were wanted for a crime in the US. If they weren’t, they'd drive them across and open the van and say, “Good luck. See you tomorrow maybe.” And that was the game. It’s not that anymore, but it’s not that because it’s important to the people who want to use immigration as a voting wedge. You’re either against these people taking over our country or not.

I did interviews for one of our movies in Berlin when the wall was still up. Berlin was a city. It was a bubble. You traveled almost two hours on the Autobahn through East Germany. You could stop and buy vodka, but you couldn’t get out of your car except at certain places to get gas and buy vodka. Then you got to West German territory again, and the wall went all the way around. There were places where it was a cement wall and places where it was barbed wire with mines.

Well, that was a symbol of the Cold War. And the people who lived there had relatives on the other side who just didn’t cross in time to avoid it. But it wasn’t really about the people. It was about the West and the Soviet Union. It wasn’t even about Germans, even though they were forced to take sides.

A lot of my movies and my books are about when we say the word “we.” How big a word is that? Who’s included in “we”? Is it just my family? Is it just the people in my church? Is it the people of my race? Is it the people of my company? If I’m in the military, is it all Americans? How big is that “we”? You have to define that constantly in your life, but there’s people more powerful than you who want to define it for you. That’s where it gets very complicated.

Let’s get back to the origins of Lone Star. The script is so intricately constructed. Where did it begin? What was the germ of the idea and how did you build it out?

If you talk about it like a screenwriter pitching it, a body is found. Along with the bones, you find a sheriff's badge, and the story was that he was a bad guy. When he was called on his badness, he chickened out and he stole a lot of money from the county and disappeared. Now we know he was found and he was probably murdered and buried out on a rifle range. Who did it? That’s the beginning.

It could be just a straight murder mystery, but then when you add that it’s on the Mexican-American border and there’s an army base in the town and [the victim] was hell on Mexicans and Black people. So who are your suspects? If I was coming from the outside as a film reader or film watcher, I would say, “Well, somebody finally got sick of his bullshit, and probably a Mexican or a Black person shot him.”

But then what if the guy who took over for him as sheriff had an almost violent confrontation with him on the night that he disappeared? Well, there’s another suspect. So you start adding that. If you think of Raymond Chandler, Raymond Chandler’s books were written by a British guy who’d been working in the US oil industry in Los Angeles and was fascinated and disgusted by American culture, and especially the low-level Hollywood angle of it.

So his books are these wonderful tours through the Los Angeles of his time, and very often it’s not that important who killed who at the end. The detective story gets you to go to all these places and it gets you into race and politics and Hollywood and all those other things. So for me, that [premise] that there’s been a murder and “who did it,” sent me off on an interesting story about our border, Texas specifically, but also about borders in general.

Of your films leading up to Lone Star, City of Hope seems strongly connected to it, in that you were trying to understand this place as an organism and using these different strands of story to evoke a place. Do you feel like City of Hope informed Lone Star in a way?

Yeah. Both of them have quite a few master shots, where the shot keeps going on without a cut, and that’s for a reason. In Lone Star, it’s about how the past is not separated from the present. These people are carrying the past, and it’s not just their past, it’s the political past. It’s the history of the border. In City of Hope, it's about these people who think they’re in these neighborhoods or these ethnic groups or these interest groups that have nothing to do with those other people, yet we the audience get to see, in the same shot, these people are absolutely connected, and what these people do here is eventually going to have serious consequences for the other people who are in the shot, even though they don’t know it. They don’t know how they’re connected or won’t accept how connected they are.

And they’re both movies that deal with these enclaves who start crossing paths and are tied in ways that they either don’t know or don’t want to admit. To me, that’s the challenge of trying to have a multicultural country. If you really look back, there was a time when a mixed marriage was between an Anglo and a Saxon. So Anglo-Saxons weren’t always on the same page either, but we got this thing that we said, “Well, oh, we’re all white here. We’re all Anglo-Saxons here,” but now these Irish show up, or these Italians show up, and how are we going to deal with them? And they assimilate to a certain extent and they don’t to a certain extent.

At one point, we decided we don't want any Japanese or Chinese here. They’re taking all the shit jobs, and we got unemployed people here, and they might take the gold, because they worked harder than we wanted to work. Let’s send them back where they came from, and we just deported a whole bunch of people. We deported Mexicans in the 30s, including Mexican-Americans who didn’t have birth certificates. We just sent them to Mexico where they had no relatives.

So that is a constant story. It’s not ever going to be solved. When people try to do it usually involves, oh, we're just going to push out or kill those people and get them out of our air. Look at the Middle East.

One very complicated argument that Lone Star seems to be making is that you have the scene, as you talked about earlier, where they’re talking about what gets taught in the school. You have that conversation about historical truth and then you reach the conclusion of the film, when the truth comes out about what happened, but it becomes useful to leave the past in the past.

People have to make the choice. So there's a character that Jesse Borrego plays, Danny, who’s the reporter, and he’s got a chip on his shoulder about Anglos and Mexicans, and he wants the real story to come out and he will publish this stuff, but it certainly is not going to get taught in school. Whatever he does, he’s screaming against a very loud noise of his state who don’t want to know that history or recognize that history.

So at the end of it, Sam and Pilar, they’re going to stay together, but they’re not going to stay in that town. They’re not going to change. They’re not going to take that statue of Buddy Deeds down. It’s a more complex history than people want to know. Sam just says, “I’m just going to leave that story to you people, but I’m out of here.” Quite honestly, I know people that are leaving Texas or Florida, because they teach in the schools and they teach history, and they will lose their jobs if they teach what they think the truth of Texas history is or Florida history is. They just say, “This is poisoning my life. I’ve got to leave. I can’t change it.”

And there's others who have said, “Well, I’m going to stay here and fight it.” But those are your choices because sometimes the story is so important to the people who have power that they’re going to maintain it and they’re going to use it to their political advantage.

You had worked with Chris Cooper, Elizabeth Peña and Joe Morton before this film had been made. Did you write with them in mind? What went into their casting?

I try not to write with people in mind because sometimes they’re not available or they can’t afford to work for us anymore, or they don’t want to do it, whatever. But after about a draft, you start thinking, “I know who would be good for this.” I don’t write for them, but it makes you feel better.

For instance, I know that Chris Cooper is comfortable riding a horse. His father was a doctor, but they had some cattle, so he rode a horse as a kid and moved cattle around. So when I made Amigo and he had to play a colonel who rides into town on a horse, well, Chris can do that. So I’m not worried about us needing a double to get a shot of this guy riding from far to close on a horse. He’s going to be fine.

It might be, “Can this person really speak Spanish?” Just because you’re Mexican-American doesn’t mean you can speak Spanish. So those things you know about people, they’ll be able to handle that. Eight Men Out, Charlie Sheen can play baseball. There’s certain things I can ask him to do. DB Sweeney went to college on a baseball scholarship. I’m going to ask him to bat left-handed. He’s a right-handed batter, but he’s a good enough baseball player. And I just said to him, “Look, you got a month or two before we start shooting this. I want you to hit a double or triple on camera without a cut, so I'm going to be behind you at home plate, and I’m going to meet you at third base. So we’re never going to lose sight of where the ball goes and what they’re doing in the outfield. Work on that.” But it wasn’t somebody who’d never played baseball before or never played it since Little League.

So you have some of those things in your pocket, but very often, I’m casting actors to do something I haven’t seen them do. Take Kris Kristofferson, I’d never seen him play just a bad guy before, but I knew he had the weight and the voice, and he’s a Texan from the border and I thought he’d be a really scary bad guy. You wouldn’t want to fuck with that guy.

When you get into the script, you start thinking of people, but you don’t necessarily write for them. The last movie that I got to direct, Go for Sisters, I wrote about two women. And the basic setup of the opening scene is one is a parole officer and she gets handed a new client and she realizes, “Oh my God, that’s my best friend from high school.”

Well, I wrote the first draft not knowing who I was going to cast, and then I thought, I know the perfect two actresses to play this. They’re African American, so the second draft included that in the world of the movie. Now I didn’t really change their dialogue very much, but the world of the movie is them coming from an African-American milieu into the world that they’re in right now in the movie.

So there’s a little bit back and forth, but quite honestly, the two things that you think about when you’re writing a movie [like Lone Star] is this is an ensemble piece. It may be a little hard to get really well-known actors to play somebody who’s not a lead, because there are no leads in this thing. And then the other thing is, if you’re writing a big part for a kid, you’re just putting yourself into deep doo-doo if you don’t find the right kid, because it’s an eight-year-old kid or a ten-year-old kid. Every once in a while, you get lucky and you get the perfect kid. And other times it's like, maybe I should take some of the lines away from this kid or work around whoever we do get.

Lone Star was a critical and commercial success, one of the biggest in your career. What do you remember about its reception and about the conversation that the film sparked? What do you remember about the experience of this film?

First of all, we got lucky in that Castle Rock put some money into it. So when the distributor went out, Castle Rock said, “You’re going to really support this thing.” So this is a movie that got more advertising and more work done on getting it to the public than any of our other movies, and it paid off. Then the reaction was, I think, “Oh, this is a really complex story. This is really about all these communities, and it goes into the past as well, not just the moment of what’s happening on the border right now.” So there was that appreciation. I think of the complexity of the story. People like the acting.

I’ve made two or three movies where at least half the story was African-American, and almost none of the reviews mentioned the Black half of the story. It happened with City of Hope. The company that released it made a trailer for the movie and at the end of the trailer, we said, “Half the story is African-American actors and there’s not a single one of them in the trailer that you made.” And they went, “Oh, really? We didn't mean to do that.” And I said, “Well, you did.” So it’s just a phenomenon of the culture that we live in is that most of the reviewers, almost all of them Anglo and white, just forget to mention them in the review.

Not that I read reviews, but people would say, “Well, it was good.” But I said, “Well, what’d they think of Joe Morton?” “Well, he didn’t get mentioned.” I said, “Come on, he’s the co-lead now!” In Sunshine State, Edie Falco and Angela Bassett, they’re on-screen together for 10 seconds, but there’s a balance to it. They have about the same screen time, but still there were reviews that barely mentioned Angela Bassett was in the movie. So the reviews are also part of the cultural wars as well.

Thank you for this interview. I adore Lone Star - probably my favorite John Sayles directed film along with Matewan. Definitely will be getting the Criterion 4K. I’ve been teaching U.S. history for over three decades, though in liberal western Washington. I love what Sayles has to say about the stories we tell ourselves and the human need to feel good about your past. As a history teacher I encounter this a lot, and often feel the need to gently persuade people to look at the ugly parts of our past. Nice to see one of my favorite film makers express that idea so well.

Fantastic interview, thorough in all the right ways. I interviewed him in 2020, titling it "John Sayles: The Griot of Late Capitalism" (https://www.dsausa.org/democratic-left/john-sayles-the-griot-of-late-capitalism) I'd love to do so again, especially because his newest novel's take on the 18th century explores what it means to be American quite differently. Do you have some words about the novels that ended up on the cutting room floor?