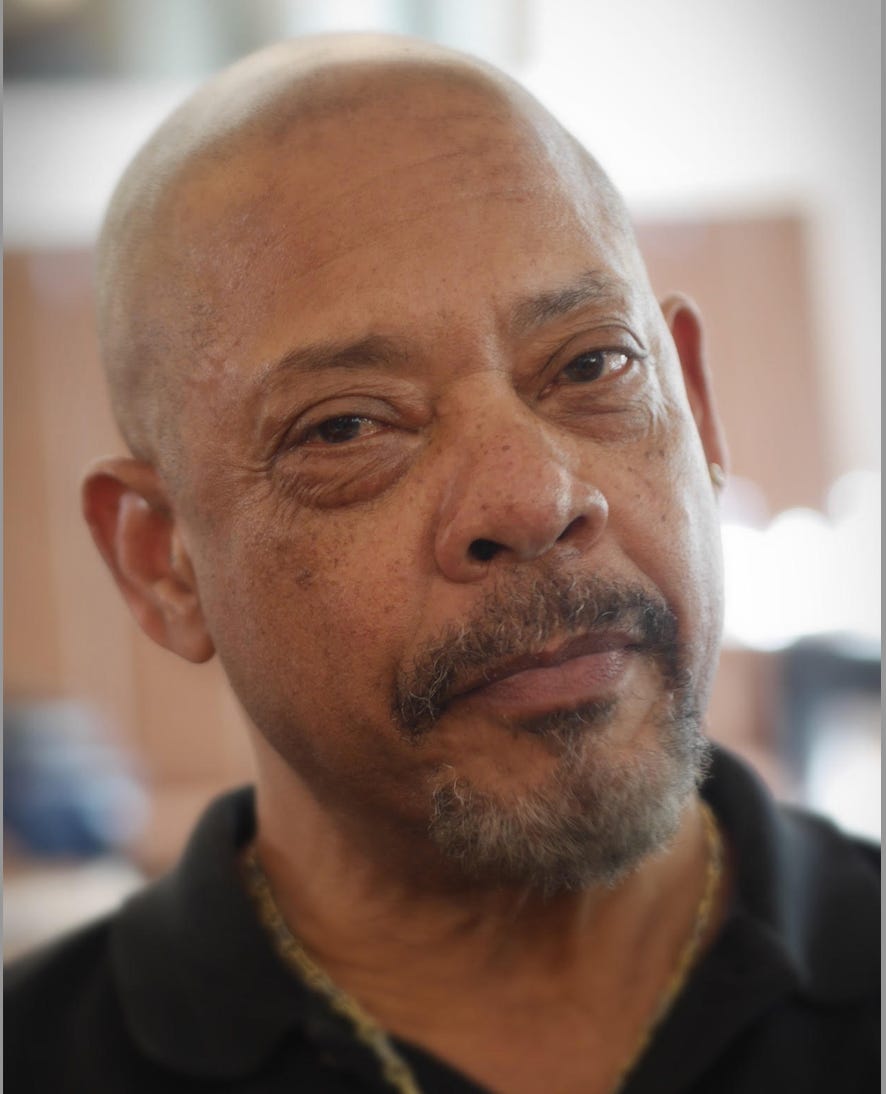

Interview: Director Carl Franklin on the career-making 'One False Move'

After two decades in the movie business, mostly as an actor, Franklin turned a 1992 crime drama into an unlikely second act.

No one has earned his success like Carl Franklin.

For the first two decades of his career, Franklin was a character actor mostly on television, with credits in some of the biggest series in the ’70s and ’80s—Barnaby Jones, The Rockford Files, Trapper John M.D., The A-Team, MacGyver, and Hill Street Blues, among others—but only a small handful of extended runs. (His role as Captain Crane on 17 episodes of The A-Team may be his most recognizable part, and that was deep down the cast list.) But in 1986, Franklin decided to reinvent himself as a director and enrolled in the AFI Conservatory in Los Angeles. From there, he immediately found work directing a trio of low-budget movies for Roger Corman at Concorde Pictures, none of them exactly résumé builders: His 1989 debut feature Nowhere to Run, a thriller with David Carradine and Jason Priestley, was the classiest of the three, but the subsequent films, 1989’s Eye of the Eagle 2: Inside the Enemy and 1990’s Full Fathom Five, were bargain-basement war movies.

But the Corman connection earned Franklin an introduction to producer Jesse Beaton, who was looking for the right (and cheap) director for One False Move, a crime drama written by the then-unknown Billy Bob Thornton and his creative partner, Tom Epperson. Beaton was impressed by Franklin’s AFI thesis film, “Punk,” and gave him the job. (And later, her hand in marriage.) Bill Paxton, in his first leading role, plays Dale “Hurricane” Dixon, the swaggering sheriff of Star City, Arkansas, a quiet Southern town that seems the likely destination of three criminals (Cynda Williams, Michael Beach and Thornton) on the lam after a series of drug-related homicides. When two seasoned L.A. detectives turn up in Star City in advance of this confrontation, Hurricane is all-too-happy to show them around, but he’s prepared neither for the danger about to descend on the town nor his own personal entanglements to the case.

Buoyed by excellent reviews from major critics—Gene Siskel declared it the best film of 1992—One False Move altered the course of Franklin’s career for three more decades and counting. In addition to other features like his superb follow-up, 1995’s Devil in a Blue Dress, Franklin has found steady work on television again, only behind the camera this time. His credits there include episodes of acclaimed series like Rome, The Pacific, Homeland, The Leftovers, and the second season of Mindhunters, a dramatization of the Atlanta Child Murders investigation, where he was responsible for the last four hours. With One False Move now joining Devil in a Blue Dress in the Criterion Collection, Franklin talked to The Reveal about the value of his time with Roger Corman, shooting on location in small-town Arkansas, and the moment he knew that One False Move was taking off in theaters.

You had directed a series of Roger Corman productions after your time at the AFI Conservatory, but it’s my understanding that your thesis film was the biggest reason you were considered for One False Move. How did this opportunity come together for you?

Carl Franklin: Jesse Beaton, who was the main producer on the film, had been given the opportunity to produce an independent film as long as she had a script that was acceptable, as long as she got an actor that they wanted, and a director who was non-union—cheap, basically. She went to several people, Anna Roth being one of them, who was one of the producers over at Roger Corman, and Anna gave her my name. So she had several other people that she had interviewed, and she saw my short, and based on thatt, she hired me to direct the movie.

What excited you about this material? What was your kind of hook into it?

Franklin: There’s scripts sometimes that you read that just jump off the page, that have a texture that’s tactile—something about it where you can almost smell it, taste it, where it has a feel. Sometimes a script is just words or whatever, but there are some where you can feel something substantive about them. So this was one of those scripts in terms of the gravity, the kinds of characters, the juxtaposition of the characters, the sweep of the story, the motivations of the characters, what they all seem to be looking to do, and the social message underneath it, which was… it was a little scary in some respects because it was art. It wasn’t didactic. It didn’t try to hit you in the face with a message. It was just so intricately woven. The social elements of it were so well-woven into the story and at the same time, while there was something political about it, it wasn’t like a lesson or anything like that. It was such a strong piece, I felt.

You had acted for quite a long time. You’d gone through AFI. You’d done these films for Corman. And now you have this script that, as you say, is very strong. What was your feeling about what this could mean for you? What were you feeling going into this production?

I had been doing Roger's movies, but at that time, the kinds of movies he was making were not the films that were going to launch you very far. I didn’t know that this one would either. It was just simply that this was a real movie in that respect. I don’t want to in any way denigrate Roger because Roger gave us all the opportunity to become filmmakers, but because of the limited budgets, et cetera, and because of the kinds of movies that we were making, it didn’t give us a chance to go that deep, and this one did.

It’s kind of interesting to think about the whole Corman piece of this, because when you talk about the Roger Corman School of Filmmaking, a lot of the filmmakers who came out of it—Coppola, Scorsese, Demme—were part of an earlier period. You came in a later period, which had to have been much more of a challenge.

Franklin: I think so too, because in the ’70s and the ’60s, Roger’s movies were going to theaters and being seen in theaters and they weren’t just a token release. Sometimes he would kind of give a token release to some of these films, just so that they could get reviewed and possibly get a good quote to go on the box. That was actually a strategy that Jesse [Beaton] employed to get One False Move into theaters. The only way was to get the film to Anne Thompson at the LA Weekly, to get the film to the Seattle Film Festival, where John Hartl saw it. And to get it to Sheila Benson, who took it aboard a floating film festival where Roger Ebert saw it, and then to convince [IRS Media] that if they gave it a theatrical release, they could put quotes from those strong responses on the boxes and sell more units. Otherwise, we were destined to go straight to video.

It was harder because the films that Roger [Corman] was doing at that point, and certainly the ones that I did, were made for video. I shot two of his films, one in Peru (Full Fathom Five) and another in the Philippines (Eye of the Eagle 2: Inside the Enemy), and they were war movies. Huge casts with tiny budgets, $200,000 to do a war film, a marine movie. You can imagine the end result. So the chances of it launching you in any way were very slim, but the experience from shooting those films was invaluable, just having the opportunity to make movies. Then of course, I did one, Nowhere to Run for his wife [Julie Corman], and of course, under his banner with Jason Priestley and David Carradine, which was a little more of a movie shot here, shot in Los Angeles, and had a little more of a chance of showing what you could do.

One False Move is talked about as sort of an important moment in neo-noir. Did you feel like you were operating in that tradition?

Franklin: The term noir never came up when we were shooting it. I looked at it as a crime drama. And even that didn’t dictate any conventions that we had to follow. I don’t know that I’d even heard the term “neo-noir” at that point. There had just simply been film noir, and One False Move didn’t look like any of the noir movies that I had been drawn to, The Big Sleep or Chinatown or Farewell My Lovely or The Maltese Falcon. I did have some of those movies in mind when I did Devil In a Blue Dress, but not for One False Move.

So what were you thinking of if you were thinking of movies when you were directing One False Move? Any models that you were sort of following?

Franklin: No. Not in terms of anything that I felt we wanted to do. There were references to movies. For instance, there was a little High Noon at the end, and an homage to North By Northwest. I did think about Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, the way that [director John McNaughton] had handled those murders was in my head a little bit too. So there were things that I thought about, but not anything that we were following throughout as a guidepost, because again, I didn’t know of any movie that I thought this resembled.

It’s interesting that you would note Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, because one of the most immediately striking aspects of One False Move is the violence, particularly the violence in the very beginning of the movie. What were you thinking about in terms of the staging of the violence and the impact it would have on the story?

Franklin: Well, I felt that it had to be real, number one. I had seen a lot of movies that summer before we began to shoot, and I thought that the effect of the films oftentimes was you would get an invigorated feeling from the violence. It’d be more of an adrenaline rush as opposed to what real violence does when you see the loss of life, which really creates this empty thing that is hard to describe. One of the movies I’d seen was Total Recall, and I remember there were lots of people getting shot, people being held up, used as shields. The only time there was any real emotional response was when the goldfish bowl broke and the goldfish were gasping on the ground, and people kind of made this, “Aww” in the theater. I wanted people to feel for these characters. So I started to look at ways to maybe to get a sense of the lasting emotional impact of violence.

One of the things I wanted and I didn’t realize at the time was kind of a local news violence. I didn't have that term, but where you would look in the newspaper and you would read about this horrible thing that had happened at a certain time in a certain city, on a certain street, and then you would see a photo of the victim, and it would oftentimes be from a yearbook or something where they’re smiling. That photo is juxtaposed against all that horrible stuff you read in the article and you get a sense of what’s been lost. So I wanted that. That was the reason for the use of the videotape in the beginning, and also just to somehow try to get the audience to identify with these people.

It was necessary to do that because of the inverted structure of the film, of the script. Normally you have a protagonist who is seeking something, like there’s been a killing and he's out there trying to solve it. He goes out into the world and comes up against the opposition and either overcomes or succumbs to it, and the resolution is whatever that he’s been able to do or not do. In this case, though, the protagonist doesn’t go out toward the enemy, the antagonist. The antagonist is coming toward him, unbeknownst to him. There was action going on, but a lot of what was happening was us understanding the protagonist. He was not engaged in real action, so to speak, until the bad guys show up in town, but we know what’s headed toward him. So that was necessary to create enough of a threat and an emotional threat so that people would be invested long enough to experience this with our lead.

By 1992, we’d seen Bill Paxton play buffoons in Weird Science and Aliens, and he was part of the vampire clan in Near Dark. What made you believe that he could pull off the dramatic notes in a role like this?

Franklin: Bill on camera, for me, had a certain kind of honesty that was also an innocence, and I felt that the challenge would be to get him to simply strip away any accessories and just to get down to him. What I saw and what we saw was a leading man, which he had not really done. So I won’t say it was a struggle because it wasn’t a struggle. He had the range to play all of those other kinds of characters and he had that arsenal at his disposal, but we had to get him to not to want to shoot all of those guns off at one time, to basically trust his own stature.

.The thing about Bill Paxton is that Bill was the type guy where what you saw was what you got. He was real. He was an honest, good guy who would just simply tell you what was on his mind. There were no complications in that respect. He was just an honest dude, and that was a very important thing for us for the Hurricane character, especially with his complexities and his complex racial entanglements.

There’s this great line in the film where Hurricane’s wife, talking to one of the L.A. detectives about her husband, says, “He doesn’t know any better. He watches television. I read nonfiction.” That feels like such a concise way of understanding who Hurricane is.

Franklin: First off, that’s Billy Bob’s line. That is a total understanding, that’s the crux of who he is, that she’s aware that her husband lives in a fantasy world to some extent. Women are often more practical than we are a lot of times. We think we’re practical, but they often can see through us, especially if they're married to us and they have accepted all of our weaknesses. [Laughs.]

They see things in us we don’t see in ourselves, and they try to foster the little boy in us to some extent, because maybe those dreams might come true, who knows? Anyway, she knew, she saw who he was, and without knowing what was coming his way, she knew the severity of what real police work is about. In other words, what she’s saying is, “I’m hooked into reality. He’s still believing in the fantasy of TV and of pop culture. And I basically know I see my husband, and that’s the thing that I worry about with him, and I hope you are not leading him down a path that is going to lead to his destruction.” She already could see the problem. It is something that… Of course, we’re feeling some dread, because we know [the criminals] are coming to Star City and we know that he’s going to have to confront what's coming his way. Somehow we know that.

There are things that Hurricane knows about his town that are actually useful, but obviously all the things that he has no experience on.

Franklin: As he said, “I’ve never even had to draw my gun.”

Right.

Franklin: To crickets. He thinks that that’s something that they’re going to say, “Oh, that’s great,” but they look at him like “Then you really don’t understand.”

What do you remember about shooting this movie, particularly when you were in Cotton Plant, Arkansas?

Franklin: It was amazing to me because we kept hearing that we can’t really go to Arkansas. But Jesse, who was the producer, was very particular about who she wanted to get as a line producer and we got this guy named Tony To. And Tony just made miracles happen, man. He was able to stretch that money. I mean, suddenly, yes, we’re going to Arkansas, we’re going to shoot there, and we’re going to be there for six weeks. I don’t know how they hooked it up or whatever, but we went to Arkansas.

It was weird. It was a town where, I would say, over half of the businesses on that main street were closed. It was in decline. There was an illiteracy rate of 30% in that town. It was a town of 801 people or 916 people, depending upon which way you came into town, because it posted two different population signs. It was a racist town. We had something to offend everybody. We had a longhaired cinematographer, we had a gay first AD. We had a woman with short hair who was our line producer. We had a Black director. We had an interracial relationship in the film. We had it all! [Laughs.]

So a mixed response to this production coming to town then?

Franklin: Oh, definitely. What was interesting was that we actually didn’t stay in Cotton Plant. We stayed outside of Cotton Plant. We were in a motel that was on the side of a highway, and because a lot of the guys [in the production] were talented, they’d play instruments or they were down dancing in the bar. It was like the circus had come to town. So people would come there because of that, because the carnie people were in town, and that’s kind of the way it was.

Six weeks sounds like a pretty decent amount of time for a production at this size. Did you feel like you had the space to do the work that you needed to do on this shoot?

Franklin: We actually shot, I think it was 30 days, because we didn’t shoot all six weeks when we were there. Some of that was prep time, about three weeks. I think we shot about three weeks, but we were there for about six weeks. Some of that was just us preparing in Arkansas. All told, I think we had 30 days, 33 days or something like that to shoot. So we didn’t have many days, but I felt extravagant, quite frankly, because I’ve been shooting for Roger, and the last movie I had shot had been a submarine movie where we had $200,000 below the line to make the movie, and allegedly the producer stole $80,000 of it, and so we had $120,000 to make a submarine film with four different nationalities—Cubans, Russians, Panamanians, and Americans—all of whom had to have different kinds of military uniforms, and on a submarine.

You just have to try to not make it seem like an Ed Wood production at that point.

Franklin: Well, it was borderline Ed Wood. Some of the submarine was built on stage, and it was like a Saturday morning kind of a set. We shot some on a real submarine. We shot two days in a submarine tied to a dock, and then we took one out that I think belonged to the military or something, and we shot exteriors of that. Yeah, man, it was wild. The dollar went a long way in Peru. [Laughs.]

So what’s the most memorable day that you had on set? Is there a moment or a scene or just something that pops in your head immediately when you think about it?

Franklin: There are a few days. One was when we shot the opening scenes, because I still wasn’t sure how I was going to do that until that day. The other was when we did pick-up shots out in the California desert when it was 16 degrees, and probably the ending when we arrived at the set and saw that the cotton fields that we thought were going to be there had been harvested. So that changed the whole ending look and the shot when we realized that we wouldn’t have cotton. I actually had a crane that day. We could afford a crane one day, and I had it, and then I couldn’t use it.

When did you realize that One False Move was going to have a life beyond what seemed like a straight-to-video destiny? What was that kind of feeling when that realization sort of happened?

Franklin: We were shooting Laurel Avenue at the time. I was in Minneapolis and St. Paul shooting this miniseries for HBO, and Jesse, the producer, who is now my wife, had been able to get [IRS] to release it in three different cities. As I said, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, because John Hartl, Anne Thompson and Roger Ebert, Gene Siskel had things to say about it. So when it opened, we started hearing that it played in those theaters. So then other theaters picked it up and we heard… wait a minute, it’s being extended in Los Angeles for a while. We're hearing Roger Ebert has just appeared on the Today Show talking about it, besides his own show. We’re hearing now that it’s extended again. Then I remember, I’ll never forget, I was casting on Laurel Avenue and just had finished with an actor, and in between that, Jesse comes running down the hall. And I know when I start crying. She said, “We have lines down the block in New York." Oh, man. I was like, “Wow.”

Great piece, thanks for doing this!

I understand that rights issues are stupid complicated, but it's sad that not every new Criterion release ends up spending some time on the Channel