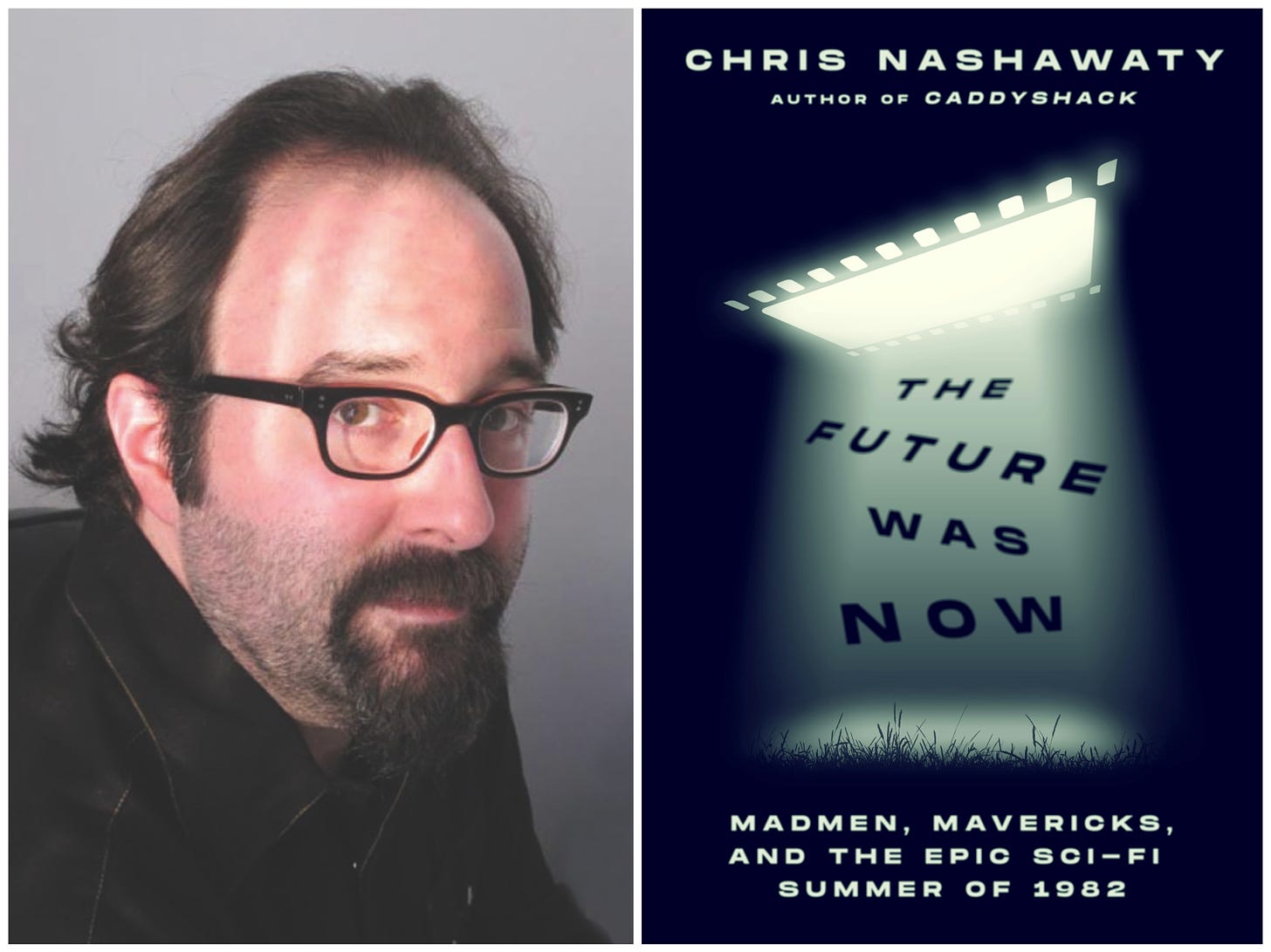

Interview: Chris Nashawaty on the Miraculous Summer Movie Season of 1982

In his new book ‘The Future Was Now,’ Nashawaty explores the summer that produced eight genre classics and how its influence has lingered for decades.

Conventional wisdom holds that you never know you’re living in a golden age until it's over. Sometimes cinematic history bears this out. In a stretch of just a few weeks, the summer of 1982 saw the American release of eight films now considered towering classics of the science fiction, fantasy, and horror genres: Conan the Barbarian, The Road Warrior, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Poltergeist, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Blade Runner, The Thing, and Tron. In his new book The Future Was Now: Madmen, Mavericks, and the Epic Sci-Fi Summer of 1982, Chris Nashawaty, a veteran film journalist and author of books about Roger Corman and the making of Caddyshack, weaves together the stories of each film’s origin, release, and legacy into an account of Hollywood as it reached a turning point. In some respects, the summer of ’82 was a culmination of filmmaking trends that had been set in motion in the 1970s, giving moviegoers eight pinnacle examples of smart, exciting blockbuster filmmaking. In other respects, it was the end of an era, the point at which the blockbuster machinery began to dominate Hollywood’s approach to making films while marginalizing and excluding other sorts of films. The Reveal spoke to Nashawaty about the summer of ’82, how it came together, and how it influenced the films that followed, for good and for ill.

I want to ask a big question first: Why do you think all these films converged on 1982? Were there any larger forces at work that made 1982 such a remarkable year?

From covering movies for a long time, I’ve sort of realized that if you want to know why a trend is happening, it makes sense to look at what happened five years earlier. That’s because it takes that long to get things going on a movie. And so, five summers earlier was Star Wars, and that really lit a fire under all the studios and made them realize maybe there's something in this sci-fi audience that keeps coming back to movies over and over again and we need to cater to them in a way that we just haven't been.

Which film did you learn the most about while writing this? I'm sure there's some you knew better than others going in, right?

I had read a lot about Blade Runner and The Thing and E.T. and Poltergeist. The two that were the biggest learning experiences for me were Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, especially since it has such an interesting backstory, and Tron. I had never really thought about what was going on at Disney at the time in the 1980s. It was a real sleepy place. They were sort of facing extinction and decided to roll the dice on this very expensive experimental film, and I thought that was really ballsy. And I don't want to get off on a tangent, but I do think that it's very instructive. I hope that someone takes this message away from the book that in 1982, Hollywood was at a bit of a crossroads in terms of chasing new blockbuster audiences and how to do that. I feel like now the industry's at a crossroads, trying to figure out the whole streamer and post-Covid thing and to operate in today's world. I found it really inspiring that, back then, the studios were willing to take gambles to get out of the problem, whereas now I feel like the studios are curling into a fetal ball and hoping it all goes away, which I don't think is the way out.

Were there any other big surprises in researching the book?

Spielberg has always been this sainted character and the book covers a period where he had his one PR crisis moment on set on Poltergeist with the whole Tobe Hooper thing and maybe trying to take credit for the film in a way that was a little bit unseemly. I also found George Miller’s story really interesting. I mean, you could just watch The Road Warrior or Fury Road, for that matter, and realize that obviously these are dangerous movies to make. But it's surprising to me that no one died on that movie, or on Fury Road too. As assured and artistic and ballsy as The Road Warrior is, it was still very much an amateur production. The lack of Hollywood checks and balances on the film was really astounding.

But the movie that had the most interesting backstory that I didn't really know that much about before was Wrath of Khan, just in terms of what was going on at Paramount at the time. And I knew that the first Star Trek movie wasn't good because I've seen it. I have eyes. But I didn't realize that if Wrath didn't work, it's very likely that Star Trek could have ended right there. Learning the inside baseball machinations at Paramount was really interesting to me, as was Gene Roddenberry potentially leaking the Spock-is-dead spoiler.

The section covering the leak of Spock’s death was pretty fascinating and captured how spoilers worked in the pre-internet era. But why do you think it became a news story? I can’t think of another case, from that time, at least, when a plot detail from a film that was still in production became national news.

As the original Star Trek series played in syndication throughout the ‘70s and early ‘80s, it snowballed into this giant, beloved cult thing. That’s stating the obvious, but I do think that people were really invested in that show. There were Star Trek conventions before any of these fan confabs anywhere. There probably wouldn't have been a Wrath of Khan without fans showing their hunger for it. So I think that’s the reason why that became a big news story: the fan base was so big and especially rabid, and this is a beloved character. It's like saying that in one of the Brady Bunches, they're going to kill off Jan.

Let’s talk about what you call in the book “the worst day in the history of film criticism.”

June 25th, 1982.

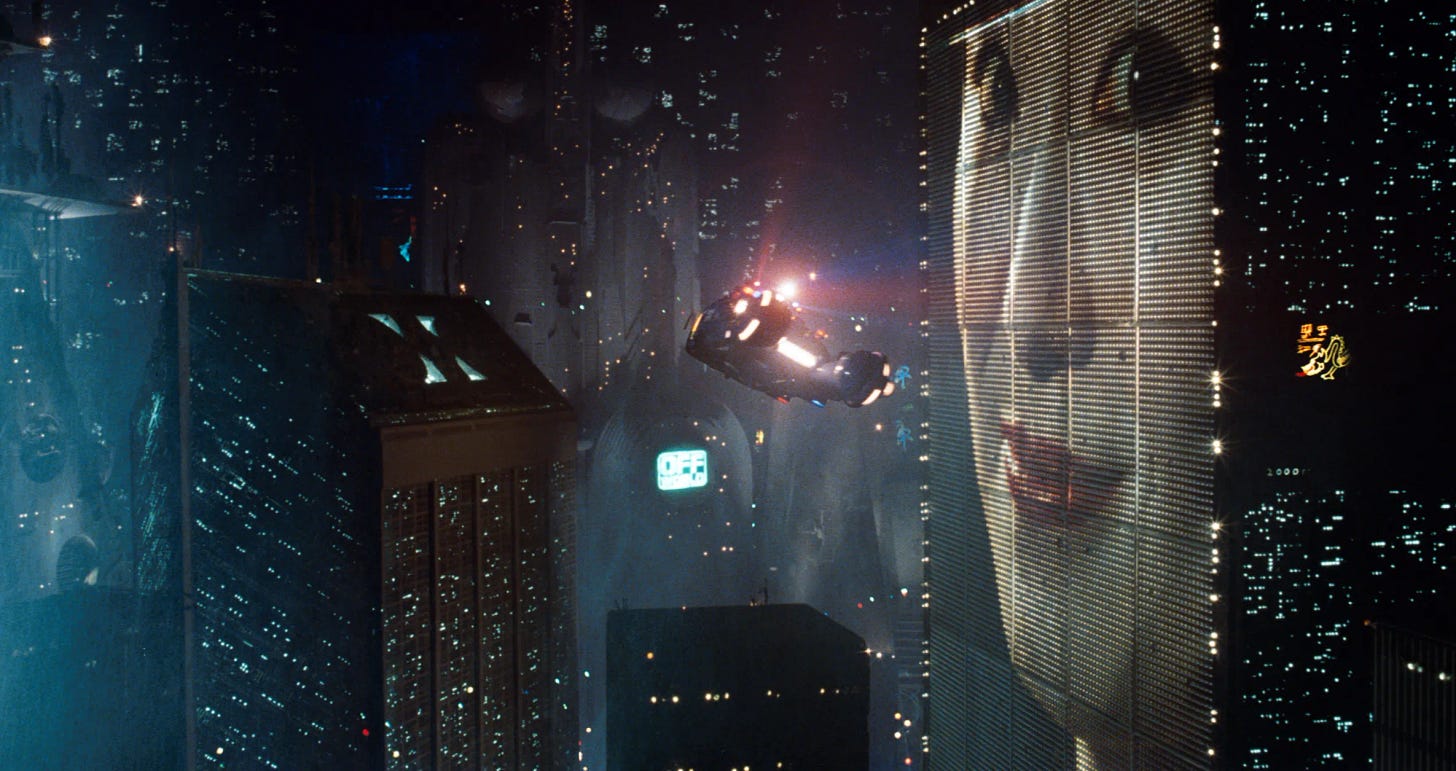

Why do you think both The Thing and Blade Runner were either misunderstood, considered underwhelming or hated? I'm old enough to remember watching the Siskel and Ebert episode where Blade Runner was treated pretty dismissively.

Let me just stop by asking you a question: How old are you?

I'm 51.

Okay, so you were nine in the summer of ’82? So did you see any of these? I'm sure you saw E.T.

Yes, absolutely. Let's see. I wanted to see Poltergeist, but I think I was too scared. I remember actually leaving the theater during a Road Warrior trailer. I was so upset. I saw Tron, The rest I saw later.

The reason I asked is because I think that at that time in the culture, there was a real hunger for optimism. We're two years into the Reagan era. I think that the sort of tilt towards conservatism is an indication that America wanted to return to some time that never existed, a happy, optimistic time. We’re coming out of Watergate and Vietnam and all these downbeat movies of the ‘70s. And I think that it's very indicative of why E.T. did so well and why Blade Runner and The Thing did so poorly. Those are very dark films with ambiguous endings, and it just maybe wasn't what people wanted that summer. I also think Blade Runner is confusing. It's why they put in the voiceover after it tested really poorly.

I watched it again last night at a screening. It was probably the 20th time I've seen it, and it's a tough film. So I get why maybe audiences were turned off, but it doesn't really explain why critics were. They should be better than that. I think if you go back and read the reviews, a lot of the reviews complain about how slow the movie is. I don't think it is, but I also think there was a level of expectations for the next film after Alien, for Ridley Scott, and the next film after Raiders of the Lost Ark for Harrison Ford. This is not a Raiders, Indiana Jones-y kind of performance from him.

Deckard isn’t even a likable character.

No, and he's also very inscrutable, and there's the whole thing about is he a replicant? It’s a lot of work to do. And so I guess I get that one, even though it doesn't make me happy. With The Thing, if you go back and read the reviews, a lot of them refer to it as a barf bag movie. The effects are really gooey and wet, And gross. They’re in your face and disgusting, and that's what they wanted to do. They made the movie they wanted to make but, again, I think that really turned people off. And Carpenter knew. He knew before the movie came out, when he started seeing how well E.T. was doing.

The Thing’s failure seemed like it really did a number on his head in terms of what to do next. I like Starman, but I can’t imagine a more Spielberg-like Carpenter movie than that one.

Well, that's maybe why he made it. He got his ass kicked by Spielberg, and it's like, well, maybe I'll try my version of a Spielberg movie, which is Starman. And I don't think he's ever come as close to making an optimistic film as Starman again. I like the movie a lot, but it's not maybe Carpenter’s natural default setting. And The Thing did zap his head for sure. He really lost a lot of confidence. He had been on a pretty good winning streak up until then, and some of the movies he made after The Thing are good, but that run he had between Halloween and The Thing is really just… That's like the ’27 Yankees.

Let’s go back to Poltergeist for a minute because the central question with that film is always who deserves credit for directing it. I've heard all different sides of the story. What insight do you have after writing this book?

My feeling is that Tobe Hooper did direct it, but I do think he was very deferential to an extremely, extremely successful producer who was on the set almost every day. And so if Steven Spielberg says to you… Even though I like Hooper as a director, and Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a really good movie, if Steven Spielberg says to you, “Hey, you might want to set the camera up here” and you're making your first studio picture, I would say “Yes.” Yes, do what Mr. Spielberg says. And I think he was probably too deferential. I think Spielberg was probably a little too attached to the project and had never really produced in the sense that taking the back seat was new to him. And so I think it was a combination of a strong producer and maybe a weaker-than-he-could-have-been director. I think Spielberg was more involved than most producers are, and Hooper was probably more deferential than most directors.

One thing that struck me is these are not necessarily star-driven films. There are stars in them, but even Harrison Ford wasn't someone whose name alone could just open a movie. Schwarzenegger and Gibson became big stars in part because of their 1982 movies. What do you think sold these films?

I think there's still a bit of the residual excitement around Star Wars and sci-fi. I do think that these fans, which is what the book is all about, for the first time saw that this was the summer for them. And I think they went to all of these movies in a really excited way. The Road Warrior really worked on a lot of levels. It worked in America, but it worked in a lot of places around the globe because it's such a universal myth, this sort of solitary figure. George Miller says in Japan, they see this as a samurai movie and in Scandinavia, they see this as a Viking saga. It's one of those archetypal stories.

Conan, of all the movies, that's the one I think that could be made tomorrow because it's got IP. It feels like a comic book. It really has that epic quality to it. Poltergeist and E.T. both have Spielberg's name on them, so there are obvious reasons why those clicked. And with Wrath of Khan, the word got out early that this was a return to form for Star Trek. Tron, I think there was a curiosity factor. Just, what is this thing? It felt like the future, but you got to kind of see it and The Thing, no one saw anyhow. So there was a combination of forces. I don't think, like you said, stars were the reason, although I do think that some stars came out of it.

I don’t think Schwarzenegger is a star without Conan, or at least not in the same way.

For sure. That was a role he was born to play. It is perfectly suited for him as a big breakout performance.

It’s funny with Conan though, because I don't know that you could launch a blockbuster franchise with an R-rated movie anymore, particularly a movie that was so happy to be R-rated. The only equivalent today I can think of is Deadpool.

I think there's a way to make Conan the Barbarian as a PG-13 movie. Well, then it wouldn't have been PG-13. It would've been PG. But when you've got a script by Oliver Stone and directed by John Milius and Schwarzenegger is in it, why not get it as bloody as possible? I'm glad it's an R-rated movie. Putting aside the most recent remake [2013’s Conan the Barbarian starring Jason Momoa], I really think that if they made a version of it tomorrow, it could have the potential to do really well. Whoever has the rights to that thing, I don't know what they're waiting for.

Do you have any thoughts about how some of the other films of 1982 kind of fit into the context of the times? You easily could have written a longer version that had Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Rocky III and others.

Yeah. I mean, there's so many good movies. I get very nostalgic for that time. They say that the music you listen to when you're 15 or 16 is what you’ll always think of as the best music. And I sort of feel that way about movies. And so the movies in 1982 hold a really special place for me, and it's not just these sci-fi ones. I mean, you look at something like Tootsie.

Studios were still making comedies for grownups. One of the big movies that year, not that I'm a fan, is The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. It's impossible to think that a Hollywood studio would make whatever the equivalent of Burt Reynolds and Dolly Parton movie is right now, because there isn't an equivalent of Burt Reynolds and Dolly Parton now. Movies don't exist for that demographic anymore. And if you go back and you look at the releases from 1982, there's still something for everyone. There's Annie, but there's Conan. There's Tootsie, but there's Poltergeist. You could go to see Wrath of Khan while your parents went to see Tootsie in the next theater and meet out in the lobby at the end, and everybody's happy. They didn't have this whole concept of like, oh, it's got to hit three out of four quadrants and blah, blah, blah.

You sort of started answering my next question. You write about Hollywood taking away the wrong lessons from this. If you can be a little more specific, what do you mean?

Well, I think that they learned to listen to the audience, right? And I feel like the industry got through a tough time by appealing to this fanbase that was previously underserved. And when they realized that this Star Wars fanbase would come for these other movies, like E.T. or whatever, I think they just sort of got blockbuster crazy. And the thing I like about the movies in the book is that they're ambitious and smart movies, and they all sort of go in different directions. They're all loosely sci-fi / fantasy, but they all push it in their own way. They really cover a lot of space in that genre. I mean, The Thing couldn't be more different from E.T., and that couldn't be more different than Star Trek. I do think that now we're just being force fed the same shit.

The lesson they learned is how to cater to this hungry audience with tentpole movies. And the lesson that they took away is they forgot about everything else that was working. And I feel like the tensile movies got dumber and more expensive simultaneously. It was overkill, so they don't feel special anymore. Just look at the Star Wars movies, which came out like boom, boom, boom. Then they were doing the shows, too, and it just felt like, wait a second. We didn't have these things for years, for decades. And now all of a sudden it's just, like, three months go by and it's another Star Wars thing, and they just beat it into the ground. I feel like that's what happened with blockbusters. When I was working at Entertainment Weekly in the ‘90s, some of the blockbusters were really still very smart, whether they were Speed or The Fugitive or whatever. Those are really great blockbusters, and I just don't get the sense, with the exception of an Oppenheimer or something, which is an unlikely blockbuster, that they're aiming high. They're sort of infantilizing the audience and it feels like we're being talked down to. I really resent it.

One last question for you. Is there another summer that you could have written this book about. I have a candidate, but I want to hear yours.

Oh, I'd love to hear a candidate off the top of my head. I don't know. I'm sort of more curious. I don't have a great answer, so I'm curious to hear your answer.

I think 1984, which had Ghostbusters, Temple of Doom, Gremlins (which I saw in theaters four times), The Karate Kid. Sixteen Candles…

That was your version of ’82.

"And I knew that the first Star Trek movie wasn't good because I've seen it. I have eyes."

Nashawaty and I are in complete agreement, as STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE indeed wasn't good: it was GREAT.

it seems pretty silly to call out critics for not appreciating BLADE RUNNER 1982 when the film's own director did not think BLADE RUNNER 1982 was a great movie, right?