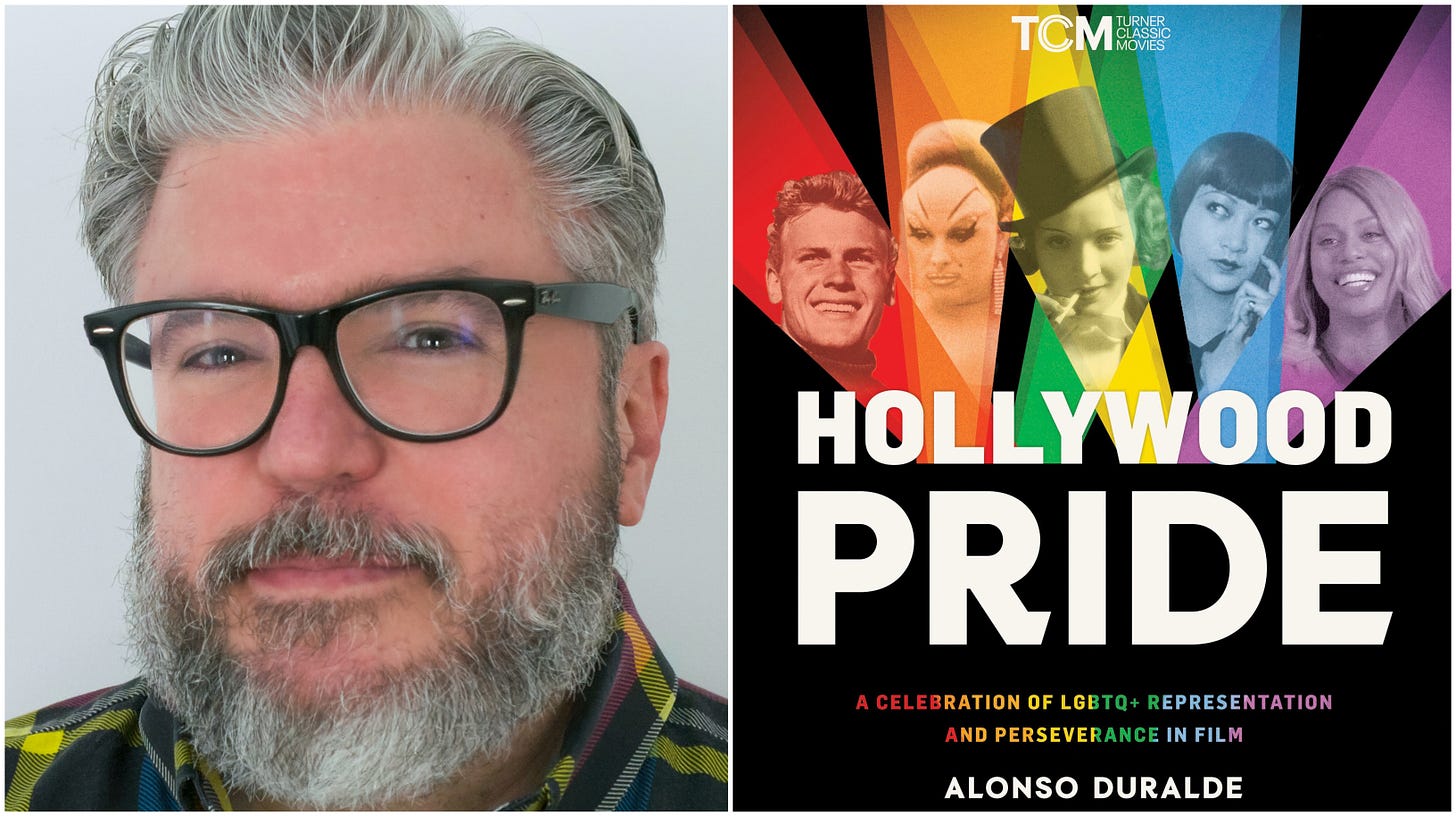

Interview: Alonso Duralde Discusses 'Hollywood Pride: A Celebration of LGBTQ+ Representation and Perseverance in Film'

The veteran critic, journalist, and podcaster discusses his sweeping new survey of the history of LGBTQ+ films and talent.

A veteran critic and entertainment journalist, Alonso Duralde has contributed to publications far and wide, including MSNBC, The Wrap, The Advocate (where he served as arts and entertainment editor), and, most recently, The Film Verdict. Duralde’s also a familiar face, thanks to appearances on TCM and elsewhere, and a familiar voice thanks to podcasts Linoleum Knife, Maximum Film!, and Breakfast All Day. He’s also written one book about Christmas movies, Have Yourself a Movie Little Christmas, and co-authored a second, I’ll Be Home for Christmas Movies. We could have talked to Duralde about a variety of topics, but we sought him out because of his new book, Hollywood Pride: A Celebration of LGBTQ+ Representation and Perseverance in Film, published by Turner Classic Movies. It’s a sweeping survey of both LGBTQ+ characters on screen and the LGBTQ+ talent that has worked in the film industry since its inception. (This Friday, Duralde will also be hosting one of a series of double features tied to the book on TCM: Caged and Happy Together.) Duralde spoke to The Reveal about what he learned while exploring this complicated, ever-changing segment of film history.

Hollywood Pride covers the entirety of film's existence. I mean, this has to be a daunting project to take on, right?

I think for those of us who've been writing for the internet for a long time, the occasional reminder of a finite space of pages and words suddenly becomes, “Oh no! It means I can't get every single thing in.” Not that even on the internet, you can get every single thing that would take forever. But I did my best to throw my arms around 130 years or so of film history as I could.

Did you decide pretty early on to cover it chronologically?

I had a couple of sort of antecedents as far as these TCM Running Press books go. There was Hollywood Black from Donald Bogle and there was Luis Reyes' Viva Hollywood. It also just also seemed to be the most logical way to try and explain things because so much of this story is tied into the idea of progress or societal change, whether it be forward or backward.

I was surprised by the number of examples you found from the silent era. How much of that were you aware of before writing this book?

Well, a lot of that comes from the people who’ve gone before me. There’s no way this book would’ve happened [or] I would still be working on it if it weren't for the work of William Mann and his book Behind the Screen and Vito Russo’s The Celluloid Closet. Both gave me a lot of information about that period. And then other things kind of popped up along the way. Tre’vell Anderson had a great book last year called We See Each Other, which threw in some of the early silent drag comedians, for instance, that I didn't know about. So everything that you're reading here is building off of a lot of existing research. And I hope that in time, this book will be the foundation of somebody else’s work.

Those drag performances are one of the first things that you hit on that’s hard to categorize as good or bad.

Yeah, I mean, drag goes back to at least Shakespeare and there's not necessarily always this sort of bad intent in producing it. It's just a question of like, “Oh, it would be hilarious if we put Wallace Beery in a dress and turned him into a Swedish maid.” And I think very often they probably weren't even really thinking about gender dynamics or that kind of thing. It was just like, this is funny, we'll do it. So I tried not to get too much into what certain filmmakers' intent might be. In other cases, obviously, you get gay stereotypes in these early silent one- and two-reelers with very swishy characterizations. That feels a little more like, all right, you have a point of view here.

You brought up William Mann. I was struck by his characterization as there being two modes of LGBTQ+ identity in classic Hollywood: “overt” and “circumspect.” I kept thinking that there have to be examples that don't fit either category, but I couldn't really think of one. How about you?

I mean, not unless you talk about William Haines after he left the studio and he and his partner Jimmy Shields were just a Hollywood couple and received as such, which was groundbreaking. And I don't know of anybody else in that period who would show up together at dinner parties, at a studio head’s house or whatever, and just be accepted as a couple in that way. But again, I think the definitions are constantly changing. If George Cukor was circumspect and James Whale was overt… I'm sure by today's standards, Whale would be looked at as rather circumspect. Nobody was pushing it too far, just because there were still a lot of legal ramifications and societal expectations about queer people knowing their place and knowing how to behave in front of the straights. I think even the people who were thought of beyond the pale, like Whale, now would seem very, very discreet.

You quote screenwriter Jay Presson Allen as noting the Code’s enforcers were not very smart and a lot got by them. What was the most outrageous thing you encountered that got by the Code Authority?

I think you look at those decades and there's just so much. The example that I cite in the book is of Joel Cairo in The Maltese Falcon. Between the gardenia scent of the calling card and him fiddling around with that cane handle, so the 90 degree cane handle is pointing at his mouth, it's like, okay, yes. I mean, Rope was made under the Code, so clearly they were not picking up on a lot of stuff. So much of the Hitchcock stuff from that period, like the woman mystery writer and her female companion in Suspicion, was just there. And I guess if you didn't put a giant neon sign on it, the censors were like, okay, I guess they just lived together.

You come back to Hitchcock a lot, discussing both examples of representation and his casting of queer actors as killers. What he’s doing is not really conforming to what everyone else is doing, is it?

No, he's definitely on his own wavelength with that. And there are certainly speculations about Hitchcock's own sexuality, which would be an entire book unto itself. But I definitely think there's a prankster side of him, that he liked seeing what he could get away with. I think he was really trying to push those sort of characterizations as much as possible. And then at the same time, there is this ongoing thing where he is tapping into the idea of the energy that closeted gay actors are bringing to these characters who are repressed or whatever. Most famously there’s Anthony Perkins in Psycho, but it’s there even before that, all the way back to Ivor Novello and The Lodger. He's sensing something where it's like, “You are somebody who is kind of living a performance already, so you're going to understand this character who has a big secret.”

You bring up Cary Grant, Randolph Scott, and a bunch of other actors about whom there’s been speculation about their sexuality. Because there is no definitive evidence, you draw no conclusions.mIs it important to find out or is it OK not to know?

I think it's always better to know. I think that there's been such a concerted effort to erase queer presence from history in general, whether it be in the arts or politics or science or whatever other innovations or triumphs that we've had. That's why I'm a big believer in saying, no, no, no, we need to know about these people because they are important and we need to know everything about them. But in the case of Cary Grant, Randolph Scott, and so many other folks, we just don't know. And there's always going to be this ongoing debate where, well, this source says that and this wife says the other thing. And so ultimately we have to live with the mystery because they're gone. Most of their peers are gone. And what does endure is the work itself.

So I think that you can draw a line, say, with Cary Grant and be like, all right, whatever we do or don't know about his personal life, here's that line from Bringing Up Baby. And here is his general mode of masculinity in the public sphere that was different from what tough guy John Wayne types were doing or whatever. Whether or not Katharine Hepburn was bisexual or trans, as I've heard theorized, she was somebody who shattered a lot of ceilings in terms of women and their representation. Yeah. Do we believe Orry-Kelly about Cary Grant? I mean, there's always going to be this kind of cloud of enigma there. So I think it's good to sort of acknowledge that the discussion exists, but not necessarily come away with any firm answers. Because there's always going to be somebody who's like, no, absolutely not, because Dyan Cannon says otherwise. So you just have to kind of go with that.

All these movies you look at reflect the era in which they were made. How quickly do you see movies reacting to major changes like Stonewall and AIDS?

There's a bit of a lag, I would say. Stonewall happens in ’69, and then you really don't start seeing even the earliest kind of queer indie feature films [until the mid-‘70s], not counting things like experimental films or even pornography, which I think, frankly, in the pre-VHS era is a way to tell queer stories that no one else was doing. You start seeing queer indies in the mid-’70s, movies like A Very Natural Thing. You get Cruising in 1980, and then I think that the studios start responding to the backlash against Cruising, and the backlash against Anita Bryant in the late-‘70s, which then brings you to 1982. And suddenly you've got Making Love, Victor/Victoria, and Personal Best. So that's about a decade or so. And then the AIDS pandemic kicks off in the early ’80s, and then it takes us until [the end of the decade] to get Longtime Companion.

You brought up Cruising, and, beyond that, you cover a lot in the book that have inspired complicated reactions: the sissy stereotype, The Silence of the Lambs, and so on. Did it feel important to remain even-handed when writing about them?

I mean, yeah, this isn't a memoir. I'm trying to sort of be somewhat objective about capturing this history, and you talk to any three or four queer film critics and you're going to get very different responses about Cruising, about Silence of the Lambs and whether or not are they good for the gays or are they fascinating films in their own right. And are these depictions problematic or are they not problematic? I mean, two trans film critics just wrote a book about Sleepaway Camp! So I think that there's not a monolithic point of view about any of this stuff. There are going to be other people within the queer community even who were like, well, no, at least we were visible on screen. Somebody asked me recently about the sissies and about Hitchcock's villains and stuff. And, look, if the Production Code was designed to just obliterate us from the landscape, then any way that we snuck onto the screen and existed in the public eye for me is a good thing. Because at least it's just a reminder that we are on the planet. While the official stance was, no, you're not.

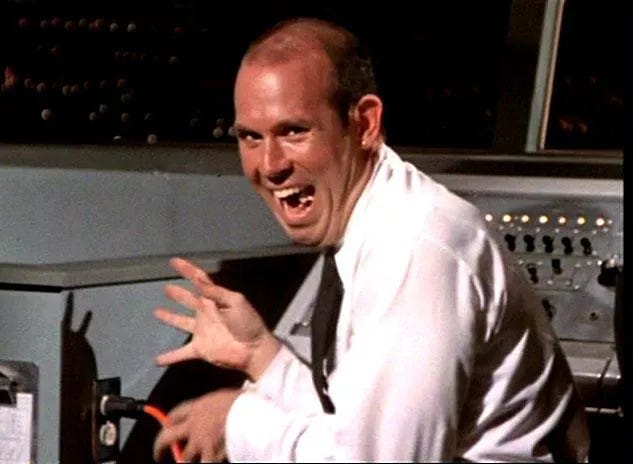

You could almost do a whole book on the evolution of the sissy character. I liked how you wrote about Airplane!’s Stephen Stucker kind of reclaiming that. Or Michael Greer in The Gay Deceivers.

I think it's because so often the sissy character… I mean, sometimes they can be kind of the butt of a joke, but very often they are in charge of their domain. Franklin Pangborn has his universe in these movies, and he's in charge, and you're just visiting. Stephen Sucker is absolutely operating on his own wavelength in Airplane!, and he's the one person in the movie who's really allowed to pursue laughs and not get laughs by playing it straight. I think that it's not necessarily a defeatist thing. I think very often they're the winners. They've got the best lines, they've got the best comeback or whatever. And so there's a lot of different ways that you can do it. And it kind of comes down to the intent of the filmmaker, the intent of the performer, and we have to kind of take them on a case-by-case basis.

You write about Guinevere Turner and Rose Troche being inspired to make Go Fish by watching the movie Switch, and a scene set in a lesbian bar. That can't be the only example of someone of that generation saying, no, we need to set the record straight, pardon the expression.

I'm sure, but that was the one that I knew about because I had Guin on a podcast where we talked about that. But Godard says the best way to review a movie is to make another movie. And so I think for a lot of people growing up with no queer visibility whatsoever or with these often negative portrayals that probably was the impetus. To be like, no, no, no. I'm going to do it my way. I'm going to show what's really happening. I'm going to give it to 'em in a way that is honest. I'm sure you could scratch many a filmmaker and get that story from them.

You’ve worked as an entertainment journalist for a long time. Was it odd revisiting the era that you were covering as it happened from an historical perspective?

A little, yeah. I was at The Advocate from 2000 to 2006, so I was there for the whole Brokeback roller coaster and a lot of other things that were emerging in that period. It's one thing to start getting gray hairs, but it's another thing to realize that a chunk of your life is now period. But it was exciting. Because it sort of allows for this thing where you kind of had this perspective, now you're like, oh, wow, that was 20 years ago. That was 30 years ago. I mean, my first job at a film festival was in 1990. I took Todd Haynes and Christine Vachon to a gay country western bar in Dallas after they screened Poison. I kind of feel like I've been on the outskirts of this story for a while now, so it’s kind of cool to sort of have it all in one place.

You refer to an expected flood of LGBTQ+ films after Brokeback Mountain that never happened. Why do you think that is?

Well, I think there's a tendency, certainly with the major studios, where when a film that is centered on queer characters, on women, on characters of color, when one of those films becomes a hit, it is a fluke. It's not like, “Oh, let's crank out 10 more of these.” Well, I mean, yeah, this one, sure. Sex and the City. Sure. Black Panther, whatever it is, there's always going to be some reason why that is this singular unrepeatable thing where everything else in Hollywood, any other success is eminently repeatable. We'll get 20,000 YA adaptations or whatever it is that is the hit that everybody wants to clone. But when it comes to underrepresented audiences like that, there's always a reason why that doesn't count.

So how are we doing today? And you also write about how television's kind of lapping movies in terms of depiction. What do you see as the present and what do you see as the future?

God only knows what the future is right now, it's just nothing but “the sky is falling” doom predictions about how private equity is destroying streaming and how streaming is destroying cinema. And so it's hard to say. But, I think that what's promising is that more and more we're seeing that mainstream audiences can handle queer narratives, whether it's a film like Moonlight or something like Everything Everywhere All at Once, both of which won Best Picture Oscars, which in the wake of Brokeback Mountain feels revolutionary. I think that we're seeing a lot of exciting talent come up. In the last year, we've had The People's Joker and I Saw the TV Glow and Bottoms and L’immensità. So many films from around the world, but particularly in the United States, I think that are giving us different points of view. I think we're having kind of a trans New Queer Cinema right now, which is very exciting.

So I think the talent is there and the stories are there and the audience is there, if someone will bother to try and find them. But I'm going to really be really interested to see how these shakeups at the top are going to affect everything else. Because I think that so many of the major studios now, between consolidation and putting all their eggs into the streaming basket, are really going to get safe and conservative. But I think there's always been that American indie sector that has managed to find its way through those corporate shenanigans and get those films made and get them out there. I hope that they do, and I feel pretty confident that they will. And in the meantime, I hope that people will support movies like Bottoms, Big Boys. and I Saw the TV Glow. That’s what generates more of it.

Before I let you go, what are a couple under-the-radar films, maybe films you discovered while writing this book, that people should seek out?

I didn't know about the Gay Girls Riding Club, which was this organization in the ‘60s. It was this kind of loose affiliation of gay men in the industry and drag queens, and they made shorts, and I think even a feature that AGFA restored recently, You can watch them on Kanopy and Tubi. They have titles like “What Really Happened to Baby Jane?” or “The Roman Springs on Mrs. Stone.” And what's fascinating about that is that James Crabe, the cinematographer for Rocky, emerges out of the Gay Girls Riding Club, which is something that would never have happened in earlier decades. Again, just overt and circumspect. Nobody who is that beyond overt would've necessarily found work within the studio system, but by this point he did. And so that was really cool.

I think that I knew about Arthur Bressan and that he made these sort of narrative dramatic films like Buddies, which was the first narrative film about AIDS,. He also made adult films and documentaries, but I saw a lot more of his stuff in putting this together. His film Gay USA is really amazing. I [recently showed] that on TCM and there's a new Blu-ray of it that Altered Innocence just put out. And this is a film from '77 where he basically had camera crews at all of these different gay pride parades in San Francisco, L.A., New York, and Chicago. And it was right after the Anita Bryant shit started going down. So there's this real sort of sense of urgency to it, and I think it's a look at kind of a pre-AIDS queer community that maybe a lot of people have never really experienced on film before.

I love Alonso Duralde's podcast Maximum Film and I can't wait to read his book. I'm off to order it now!

Great interview! I’m glad Duralde brought up Arthur Bressan because his films are real eye-openers. I’ve seen two of his adult films — PASSING STRANGERS and FORBIDDEN LETTERS — and there’s so much going on in them beyond the sex scenes.