In Review: 'The Velvet Underground,' 'Bergman Island,' 'The Last Duel'

A robust movie week offers Todd Haynes' documentary about the influential rock band, Mia Hansen-Løve's meta-movie about married filmmakers in PersonaLand and a lively return to form for Ridley Scott.

The Velvet Underground

Dir. Todd Haynes

110 min.

The Velvet Underground were a band like none that had come before, but they didn’t emerge from nowhere. A specific collision of personalities and circumstances allowed the group to take shape in an era that wasn’t naturally hospitable to its mix of chugging rock and roll, avant-garde classical music, and lyrical snapshots drawn from an underworld of drugs, dangerous assignations, and unexpected tenderness. Director Todd Haynes establishes just how inhospitable in the opening moments of The Velvet Underground, his simply titled, hypnotically paced documentary about the band. As a viola swells and squawks a black screen gives way to a clip of the game show I’ve Got a Secret featuring the man who’d produce those squawks a few years later: a young, unsmiling musician from Wales named John Cale. On the show, his discussion of having recently participated in a nearly 19-hour concert performance of an Erik Satie piece is greeted with peels of laughter.

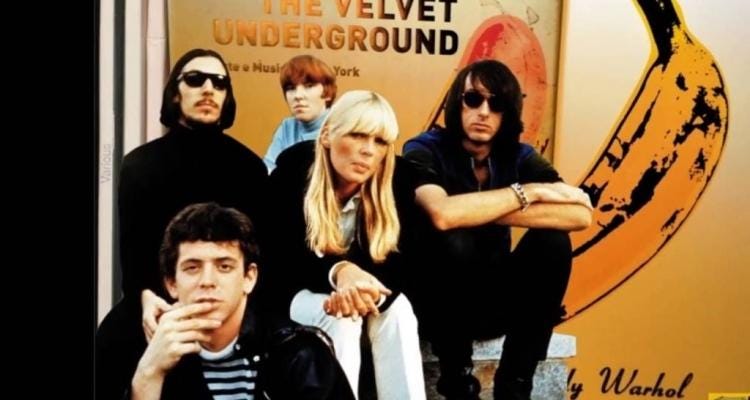

But Cale had another secret: he was beyond caring, an exemplar of a ’60s bohemia that shared virtually no common ground with the flowers and sunshine of the era’s more visible counterculture. He’d arrived in New York to further his studies and fallen in with a group of like-minded musicians who saw in drone and repetition a way to break down musical borders. The squares could laugh all they want. In the Brooklyn-born, suburbs-raised Lou Reed, he found an unlikely but remarkably simpatico creative partner, a student of doo-wop and beat poetry then working as an in-house songwriter for a bargain basement New York label. One-by-one, the pair picked up the other collaborators who would define the band’s sound: expressive guitarist Sterling Morrison, no-nonsense drummer Maureen Tucker, artist Andy Warhol (who took the band on as a kind of project), and, for one album only, guest vocalist Nico, a German singer and actress whose striking looks and icy deadpan voice complemented Reed’s half-sung delivery.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

Really everything about the Velvet Underground was brief, except its lasting influence: Nico’s time in the band, Cale’s tenure (which ended after two albums), its touring career, its very existence. Discounting a few in-name-only years after Reed’s departure, the group lasted from 1965 until 1970, during which it released four proper albums. But Brian Eno’s quote about how only 30,000 people bought the Velvet Underground’s first album but every one of them started a band may not go far enough. There are bands that owe their whole existence to single Velvet Underground songs.

Capturing the minute details of all that tumult while conveying what made the band so remarkable is a lot to ask of a feature-length documentary. Haynes smartly opts for an impressionistic approach, never dwelling long on a particular element before moving on. Reed’s high school friend and sister, for instance, both cast doubt on his oft-repeated account of receiving shock treatment in his teen years to “shock the gayness out of him,” and Haynes lets their statements stand, knowing there’s no real way to settle it, and too much more ground to cover anyway. It’s a drifting film, moving on a sea of music and archival footage from biographical and historical detail to interview subjects’ memories, often presented in split-screen compositions. That’s a tip of the hat to Warhol’s movies, but it also serves well a subject defined by overlapping elements: the sensibilities of Cale and Reed, art and rock and roll, the underground and the overground, psychedelic escape and narcotic annihilation, the ’60s as a time of boundless possibility and the decade as it was actually lived by misfits on city streets.

By the end, The Velvet Underground has become a patchwork that, put together, tells a surprisingly coherent story. In some ways, it’s a pretty familiar rock and roll tale, one in which early ambitions give way to disappointments, in-fighting, disillusionment, and dissolution. But it’s also a testament to just how extraordinary the band was, however ordinary its arc. Warhol’s keen, distant artistic sensibility and marketing savvy helped introduce them to a larger world, but, even after taking on Nico at Warhol’s insistence, the band remained stubbornly committed to its own vision, in which elusive feelings, nagging doubts, inchoate longings, and other hazy moments inspired music of pounding surety and disarming beauty. Haynes captures both the spirit of the music and the times but also a sense of why those viola squawks and what followed them mattered so much then and still matters now. — Keith Phipps

Bergman Island

Dir. Mia Hansen-Løve

113 min.

The new Mia Hansen-Løve film Bergman Island is not a horror film, but when a nice Swedish woman gives a couple of married filmmakers, Chris (Vicky Krieps) and Tony (Tim Roth), a tour of their new summer rental on Fårö, a sun-kissed idyll on the Baltic Sea, it feels like a realtor’s tour of the Amity house. She cheerfully informs them that this is the place where Ingmar Bergman, the legendary director, shot 1973’s Scenes From a Marriage, a film that inspired millions to get divorces. Don’t go up those steps, Chris and Tony! Bergman was married to five different women! Your shaky relationship will not survive sleeping in his cursed bed!

Still, there is a conceptual tidiness to setting a film about filmmakers in the PersonaLand, especially when you know that Hansen-Løve herself is in a partnership with another director, Olivier Assayas, whose relationship history includes a brief marriage to Maggie Cheung, the Hong Kong actress he directed in Irma Vep. (And Clean, after they divorced.) No doubt Hansen-Løve wants to toy with the relationship between fiction and reality, but she runs the significant risk of making a meta-movie with too-obvious parallels between the fraught relationship in Scenes From a Marriage and the one playing out in the film—and perhaps, if gossip-minded cinephiles care to speculate, another one playing out off-screen. There’s also the danger of larding the film up with Bergman references, or mimicking the famed austerity of his style.

Hansen-Løve’s elegant solution to these potential problems is simply to make a Mia Hansen-Løve film, a gentle-toned and multi-layered relationship drama that weaves past and present while reflecting on the thorny dynamic of artists living under the same roof. Bergman is treated like a ghost that occasionally haunts his guests, but exists just as often as the branding on a bourgeois vacation spot, complete with Napa Valley-like bus tours through important locations. (Through a Glass, Darkly, the first in Bergman’s “God’s Silence” trilogy, plays mutely on a screen in the front of the bus, inspiring little more than one passenger to debate whether what Bergman did could be called a trilogy at all.) The plain fact is that Fårö is a beautiful place, and it seems perplexing to the characters that such a setting could accommodate his dark moods.

The first important difference between Bergman Island and the master’s own films is that Hansen-Løve isn’t given to the lacerating swings of a Bergman drama. To the extent that Chris and Tony’s relationship is in trouble, it’s more like a hairline crack than a glass-shattering philosophical crisis. The distance between them is carefully measured, just enough to serve as a catalyst for Chris on a personal and creative journey. It starts with a little professional resentment: Tony is breezing through his latest screenplay, and has developed enough clout to sell out a “masterclass” of admiring fans on the island. Chris describes her own process as “torture,” and ends off wandering off on her own.

As Tony takes the official Bergman tour, Chris opts for a looser, more personal one with a cinema studies student, and the experience seems to trigger something within her. In the film’s most arresting stretch, she tells a half-interested Tony about the outlines of a story that Hansen-Løve stages as a movie-within-a-movie: It’s about a young filmmaker named Amy (Mia Wasikowska) who travels to Fårö for a wedding that reconnects her with Joseph (Anders Danielsen Lie), who was her first boyfriend as a teenager and a lover again when they were in their late 20s. That spark hasn’t gone away, but it’s complicated by romantic relationships both have back home and the likelihood that the third time will not be the charm.

The worst that could be said about Bergman Island is that the movie-within-the-movie features a much more compelling relationship than the movie itself, but the interplay between them is important and deftly managed. Chris and Tony are in a different phase of their lives than Amy and Joseph; the younger couple still has an electric chemistry, but the one time Chris slinks into Tony’s office wearing only an unbuttoned dress shirt, his sexual interest is zero. Bergman Island recalls Hansen-Løve’s best film, 2011’s Goodbye First Love, in its insight into what happens to love over time, how it can’t be the same in the phases of adolescence, young adulthood, and middle age. Through Krieps’ subtly modulated performance, Hansen-Love allows lament, not torment, to be the dominant mood. Bergman would never. — Scott Tobias

The Last Duel

Dir. Ridley Scott

152 min.

From the beginning of his career, when the critic Anthony Lane quipped in a Good Will Hunting review that he couldn’t pass for Cary Grant’s bellhop, Matt Damon has never had the natural movie-star charisma of his friend Ben Affleck, and nothing in the nearly 25 years since has disproven that assessment. Instead, Damon’s chameleonic quality—his wanting to be someone that he isn’t—is his defining feature, which is why The Talented Mr. Ripley is his signature role, because acting the part so often demands a visible and determined effort. (He didn’t have the movie-star charisma of Jude Law, either.) As the knight Jean de Carrouges in The Last Duel, Damon is not so much blank slate as block of granite, a dull-featured brute whose commitment to honor and duty draws snickers when he’s not looking. The guy is trying too hard and it’s not cool, even in medieval France.

Still, Jean de Carrouges is understood as a good and honorable man, plainly better than Count Pierre d’Alencon (Affleck), a self-indulgent and cackling louse, or King Charles VI (Alex Lawther), a sniveling runt playing dress-up in regal gowns, or Jacques Le Gris (Adam Driver), a strapping squire with the dark charisma of a ladies man. The plot centers on de Carrouges’ wife Marguerite (Jodie Comer) accusing Le Gris of sexual assault. That de Carrouges turns out to be woefully inadequate in responding to his wife’s sexual assault makes him a less good and honorable man, the product of a centuries-old patriarchal society that considers rape a property dispute and delivers justice in the form of a winner-takes-all public spectacle. Never has the phrase “May the best man win!” seemed so drearily relative.

Based on Eric Jager’s book, The Last Duel brings Damon and Affleck together as screenwriters for the first time since 1997’s Good Will Hunting, though their co-writer, Nicole Holofcener (Lovely and Amazing, Enough Said), certainly seems like a necessary voice in the room. It’s perfectly fitting that two men and a woman should collaborate on a Rashomon-like tale about a rape, told from the varied perspectives of two men and a woman. But where Akira Kurosawa’s film is about the slippery nature of truth, which can’t always be triangulated so easily, The Last Duel makes it clear that the woman’s recollection is correct. The truth being exposed here is how society processes it—and, the film suggests, how these injustices persist in the present day.

Opening in the year 1386, a time that kept men like de Carrouges inordinately busy, the film divides neatly into three points-of-view: First de Carrouges, then Le Gris, then Marguerite, who accuses Le Gris of forcing his way into their home and raping her in her bedroom. Much of the de Carrouges section, by far the least compelling in the film, details a friendly rivalry between him and the squire Le Gris, who doesn’t have his moral fortitude, but shares a common valor on the battlefield. When Marguerite tells her husband about the rape, he’s more concerned with propriety than her well-being, much less finding justice on her behalf. It’s a grievous insult to him that this has happened and Le Gris must pay.

The Last Duel, Scott’s 26th feature, brings him all the way back to his first, The Duellists, an absurdist historical drama about rivals who stoke a minor grievance into a lifelong series of sword and pistol fights. Much like de Carrouges here, their blind loyalty to power feels to them like honor when it’s actually folly, keeping them from any reflection on why they’re still at odds. It also brings Scott back to Thelma and Louise, a road movie that also pivots on rape, sending two women on the run from the authorities—and, by implication, from the world of violent, domineering men. Marguerite doesn’t even have the agency to drive herself off a cliff—or gallop herself off a castle wall, to make the gesture more period-appropriate—so Scott keeps the camera close to the victim, who asserts herself to dangerous limits, but still suffocates as the men on all sides take over.

What’s most surprising about The Last Duel is its tonal audacity—an anachronistic bawdiness that would seem to undercut the seriousness of its themes, but instead gives the film a great sense of irony and satirical bite. It all starts with Affleck’s count, whose language and countenance is more 21st century than 14th, but whose rich-guy arrogance reads as authentically timeless: he’s secure in the knowledge that he and buddies like Le Gris will never be held to account. Affleck, Damon and Holofcener’s script gains in confidence and swagger as the action loops back and Le Gris and Marguerite’s stories are told, with marked differences between them. At a certain point, The Last Duel can only laugh at these disparities, along with a grotesque perversion of justice and, finally, a showdown that reduces it all to a pointless, gruesome display of misplaced masculinity. The film asks with force how much we’ve actually progressed in the centuries since. — Scott Tobias

Still stoked to see the VU Doc but disappointed that we don't get much in the way of Yule-era focus. I get that Cale is alive and infinitely cool and that Warhol-era is more in the direct bullseye of what Haynes cares about but sad that the part where they hard shift into different sounds probably gets treated as a "then this happened, then The End" kind of thing.

Oh man, this is the review that has me excited to see The Last Duel.