In Review: 'The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes,' 'Dream Scenario,' 'Fallen Leaves'

What do The Hunger Games and Aki Kaurismäki have in common? Surprising fourth entries in planned trilogies. Also, Nicolas Cage is the man of your dreams.

The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes

Dir. Francis Lawrence

158 min.

In Suzanne Collins’ first Hunger Games book, and the 2008 adaptation that followed, the dystopian world of Panem was hosting the 74th Hunger Games, an annual televised bread-and-circuses bloodbath in which two children from each of the 13 impoverished districts surrounding the Capitol would compete in a death match. The question of how this authoritarian hellhole came to pass wasn’t anything Collins cared to answer at the time, other than suggesting the Games as a tool to suppress the great unwashed and keep President Snow in power. But Collins’ original trilogy was a sensation, as were the four films that followed (the third book, Mockingjay, was broken into two ungainly parts), and now a prequel, The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes, is here to fill in some backstory about the Games and Snow.

This doesn’t sound like a promising exercise, as we’ve learned from nearly every franchise prequel since George Lucas decided to dig into Darth Vader’s origin story. Presumably, Collins started The Hunger Games where she did because she cared less about how Panem became a dystopia than a moment when her plucky heroine, Katniss Everdeen, used the Games to ignite a revolution. Yet she does make some unexpected choices that turn The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes—the film adaptation, anyway—into a less conventional prequel, even as it drearily reproduces the formula of the previous films against a bleaker backdrop. It is neither a history of Panem’s Hunger Games era nor a misunderstood supervillain story along the lines of Disney’s Maleficent or Cruella. Much of the time, though, the ambiguity is hard to distinguish from the murk.

Opening 64 years before the events of The Hunger Games, the film hints at the terrible war that fractured Panem into an ascendent Capitol and the 13 districts under its control, but 18-year-old Coriolanus Snow (Tom Blyth) is far from his eventual perch. His late father was a rebel in the war and the once-prominent family is now down to three people, including his grandmother (Fiannula Flanagan) and his cousin Tigris (Hunter Schafer), all living hand-to-mouth in a dilapidated home in the Capitol. His one hope is to earn a prize from his schooling that will lead to a more prosperous future, but there’s a catch: He and other students hoping to win the prize must successfully mentor a “tribute” for the 10th Hunger Games.

It’s a little unclear whether coaching a tribute to victory will actually be the goal here, since the Games, devised by the miserable Cas Highbottom (Peter Dinklage), aren’t attracting the public interest that Dr. Volumnia Gaul (Viola Davis), the vicious head gamemaker, seems to want. But when Coriolanus gets a look at his tribute, a feisty District 12 musician named Lucy Gray Baird (Rachel Zegler), he starts to imagine the possibilities to use her voice to seduce the public and his guile to help her survive in the arena. Naturally, there are some trust issues between the two, but their interests would seem to be aligned: If Lucy Gray follows Coriolanus’s guidance and wins the Games, then both of them will get what they want.

Or will they? Songbirds & Snakes functions best as a demonstration of how an authoritarian system can shape the consciences of those who live within it—or, perhaps, in Snow’s case, reveal who they really are. Snow’s affection for Lucy Gray is legitimate, but his ambitions to survive and restore his family to a higher social station are significant, too, and he’s forced into increasingly difficult choices. Perhaps he’s a version of the evil, duplicitous President Snow played so insinuatingly well by Donald Sutherland in the original films, but Songbirds & Snakes casts him as more of a pragmatist with dangerously flexible loyalties. He’s in his own arena, too, and he needs to be the victor.

Yet the film is often a brutal dirge and its echoes of Hunger Games movies past are not well-served by Zegler’s miscasting as Lucy Gray, a character so strongly in the mold of Katniss Everdeen that comparisons to Jennifer Lawrence are as inevitable as they are unflattering. Lawrence carried her experience as a tragically burdened Ozark teenager in Winter’s Bone to the role of a symbol of District 12 grit, but Zegler seems more like a try-hard theater kid affecting a broad regional drawl between big production numbers. A prevailing joylessness seeps into this very long film, starting with an arena that’s rudimentary and under-imagined, with only Jason Schwartzman, as the wisecracking commentator/weatherman Lucky Flickerman, providing any levity. This particular dystopia isn’t worth the pain. — Scott Tobias

The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songsbirds & Snakes opens in theaters everywhere tomorrow.

Dream Scenario

Dir. Kristoffer Borgli

100 min.

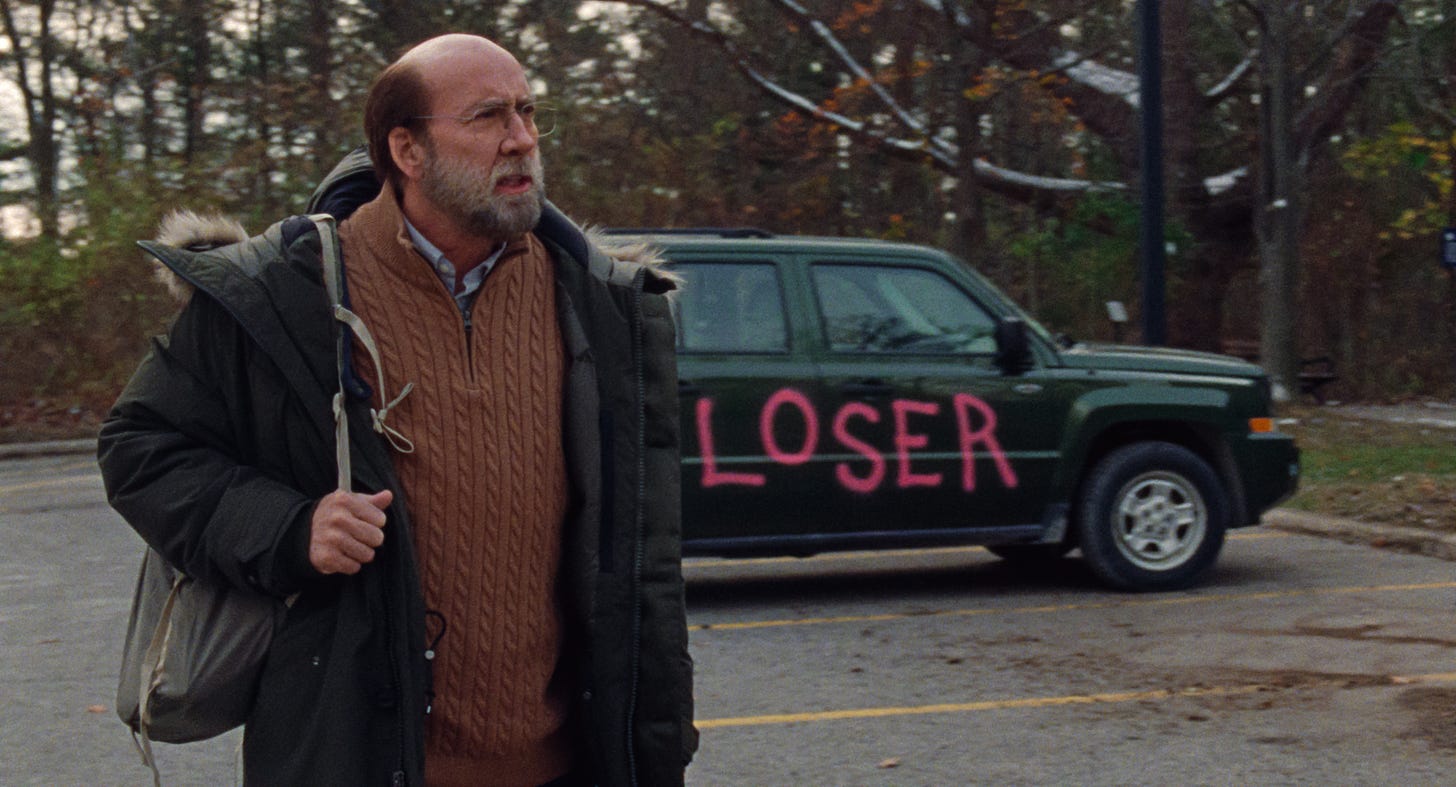

At first it’s funny, maybe even a little flattering, when people start telling Paul Matthews (Nicolas Cage) that he’s been turning up in their dreams. A bald, slouching professor of evolutionary biology with a fondness for baggy, beige clothes, Paul is mild-mannered to a fault. He has vague plans to write a book someday but can barely bring himself to raise objections when a fellow professor from his grad school days has taken some of his ideas and run with them. He’s more passionate in the classroom trying to explain how zebras’ markings work by allowing members of a herd to blend in with one another, thus throwing off predators. Paul understands going unnoticed. He has an unremarkable career, a good-enough relationship with his wife Janet (Julianne Nicholson), and a pair of daughters who don’t seem to hate him. He’s almost defiantly unmemorable, not the sort of person who seeps into anyone’s unconscious life.

So perhaps it’s not too surprising then that, when he starts showing up in the dreams of others, he doesn’t really do much, wandering by accidents, crimes, and horror movie episodes while showing only flickers of curiosity. But as unremarkable as Paul is, the phenomenon itself is pretty remarkable and quickly makes the jump from conversations among those who know and recognize Paul to an international news story. In the process, Paul becomes a celebrity, a burden he’s not ready to bear.

An absurdist comedy with powerful melancholy undercurrents, the third film from Norwegian director Kristoffer Borgli (Sick of Myself) feints at focusing on a single theme but never commits. Dream Scenario begins as the portrait of a man unwittingly in the midst of a mid-life crisis before shifting into an exploration of a celebrity, then notoriety and cancellation but this plays less like an escalation than a drift. Mostly, that’s a feature not a bug. Borgli emphasizes the mundane details of Paul’s life, saving the visual fireworks for the mostly brief trips into the unconscious. (In one memorable scene, as Paul’s dream self has started to grow more active, a character fixated on him can’t quite keep the reality of Paul from overwriting the man in her dreams.) But Dream Scenario has the floating pace and amorphous logic of an extended dream, all of it anchored by Cage’s wistful, sad performance. Paul’s situation keeps changing shape, but each new stage reminds him of how much he’s left unsaid and undone and, in the film’s haunting final image, what he’s lost that he’ll never find again, except in dreams. —Keith Phipps

Dream Scenario is currently in select theaters and expanding to others tomorrow before going wide in early December.

Fallen Leaves

Dir: Aki Kaurismäki

81 min.

Early in his career, Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki made a series of films called the “Proletariat Trilogy,” starting with 1986’s Shadows in Paradise, continuing with 1988’s Ariel, and ending with 1990’s The Match Factory Girl, an astonishingly bleak and brilliant film about a poor, lonely working-class woman who finally answers the miseries of her life with destructive action. That last film remains an anomaly for Kaurismäki, who has consistently chronicled the lives of Finland’s eccentric outsiders with deadpan minimalism and a quiet, abiding affection, but never again gone to such extremes. Now 33 years later, he’s made the trilogy a tetralogy with Fallen Leaves and a warm, even romantic optimism defines the film, even as Kaurismäki remains keenly attuned to the instability and austerity of hand-to-mouth laborers.

Looking remarkably similar to Kati Outinen, the star of Shadows in Paradise and The Match Factory Girl and seven other Kaurismäki films, Alma Pöysti stars as Ansa, a blonde lonelyheart first seen stocking shelves at a supermarket. Part of her job is swapping out expired food and throwing it in the dumpster, but when security catches her tucking some away for herself and giving other items to a beggar, she’s fired. She uses all the cash she has left for a half-hour’s time at an internet café—she gets a free coffee with it—just so she can score a dishwashing gig at a pub whose shady owner sells drugs out back. Not exactly steady work.

Love of a sort is in the air, however, when Ansa meets Holappa (Jussi Vatanen) at a karaoke bar one night, but their tentative romance is threatened by his drinking, which she can’t abide. When asked by his buddy (Janne Hyytiäinen) why he’s so depressed all the time, Holappa admits that it’s because he drinks too much. So why does he drink? “Because I’m depressed,” he says. His habit loses him job after job on construction sites, and it’s the only real obstacle to his relationship with Ansa, who doesn’t ask much more from him. Fate keeps them apart, too, through the cruder machinations of Kaurismäki’s screenplay.

The look and tone of Fallen Leaves will be instantly recognizable to Kaurismäki’s fans: His colorful assortment of melancholy, chain-smoking barflies; his eclectic Wurlitzer selections (god bless that Finnish cover of “Mambo Italiano”); and his love of the movies, which manifests itself here in a screening of his longtime friend Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die and a Chaplin reference that’s utterly charming. Without minimizing the day-to-day hardships that people like Ansa and Holappa face to maintain their no-frills lifestyle, Kaurismäki’s faith in their ability to find some measure of contentment in each other gives Fallen Leaves a special poignancy. The proletariat can perhaps find happiness off the clock. — Scott Tobias

Fallen Leaves opens in limited release on Friday.

I saw Dream Scenario a couple weeks ago at the Virginia Film Festival and it haunted me for the rest of the night. Paul is a pathetic sadsack, but he's still got a good life going when unexpected fame intrudes. Even as he makes his own bad decisions it's hard not to feel sorry for him as the world starts projecting things on to him.

Apparently Cage took the role because it spoke to him about how he lost control of his own public image.

I seem to recall Kaurismäki saying he was retiring after 2017’s THE OTHER SIDE OF HOPE, so I’m glad that didn’t stick. Looking forward very much to seeing FALLEN LEAVES if and when it makes it to my neck of the woods.