In Review: 'Poor Things,' 'The Boy and the Heron'

The fantastical, unmistaken worlds of Yorgos Lanthimos and Hayao Miyazaki.

Poor Things

Dir. Yorgos Lanthimos

141 min.

Starting with his breakthrough film Dogtooth, Yorgos Lanthimos has shown an interest in how human beings are constructed, particularly in isolation, where their inputs are limited. In the fenced-in compound where three adult children are kept without knowledge of the outside world, the parents have the power to give different words alternate meanings (“sea” means “chair,” “highway” means “strong wind,” etc.) and suggest danger where it doesn’t exist. Among other things, Dogtooth works as an absurdist comedy about how autocratic regimes work, with the parents as cruel stand-ins for dictators who propagandize their populations into submission. At the same time, Lanthimos believes in an inherent curiosity, often for carnal knowledge, that can break people out of this mental prison.

It feels extremely weird to claim this about a comedy so relentlessly eccentric and perverse, but Lanthimos’s new film Poor Things, based on Alasdair Gray’s 1992 novel, plays like Dogtooth for the masses, teasing out many of the same ideas with more of a mainstream kick. (Relatively speaking, of course.) In a word, the film is a hoot, an outré adventure that pulls heavily from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but with a deconstructive feminist angle that pairs uncannily well with Barbie, another comedy about a naif who discovers the patriarchy and figures out how to wriggle her way through it. Much like Lanthimos’ previous effort, The Favourite, the film is shocking by description yet remarkably palatable and hugely entertaining in execution. A neat trick, that.

Set against a fantastical, turn-of-the-century steampunk backdrop, Poor Things wastes little time in introducing Bella Baxter (Emma Stone), a peculiar woman whose awkward gait, stunted speech and odd spasms of behavior suggest either someone physiologically disabled or not of this earth. It turns out that Bella is the Frankensteinian creation of Dr. Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe), a brilliant and ethically liberated scientist who has forged her from the body of a dead woman and the brain of an infant. Godwin recruits a student, Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef), to observe Bella’s development, but the two men eventually find that Bella’s thirst of knowledge—and passion for self-stimulation (“Belle discover happy when she want”)—is hard to contain in their a lab setting.

When a sleazy lawyer, Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo), discovers Bella and runs off with her, Poor Things shifts into a globe-trotting odyssey from the seas of Lisbon to the scorching heat of Egypt to the streets of Paris—all rendered in hyper-real bursts of color that pop in contrast to the austere space of Godwin’s home laboratory. In a performance that meshes great physical and verbal choreography, Stone plays Bella like an accelerated Benjamin Button, a woman-child who talks funny and throws tantrums, but absorbs the world around her like a sponge. That her dad (“God”) is a sweetly deranged “man of science” and her home is a lab results in hilarious outputs, like her tossing around a word like “empirically” while not knowing what a banana is.

Poor Things is never better than in the earliest scenes with Wedderburn on a high-end cruise ship, when Bella has discovered her sexuality, but hasn’t been socialized enough to relate easily to other people. (“I must go punch that baby,” she casually announces at dinner during a disruptive cry from another table.) Afterwards, Wedderburn counsels her only to speak banalities like, “How do they get the pastry so crisp?”) But with more knowledge and greater maturity—again, both extremely relative—Bella starts to learn about poverty, injustice, and exploitation and naturally asks herself bigger philosophical questions about humankind and her purpose in the world.

There are times when Poor Things seems a bit too pleased with its own cleverness, but then again, it should be a little pleased about how easily its explicit shocks can be digested. By combining Bella’s innocence with a small child’s vulnerability and accumulation of knowledge, the film slips easily into the perspective of someone who’s discovering the corruptibility of adults without aging into it as other adults do. Her insights on inequality, say, or the complications of female pleasure are simple yet contextually profound, because certain realities we take for granted are completely new to her. Her quest for self-knowledge becomes our own. — Scott Tobias

Poor Things opens in limited release tomorrow.

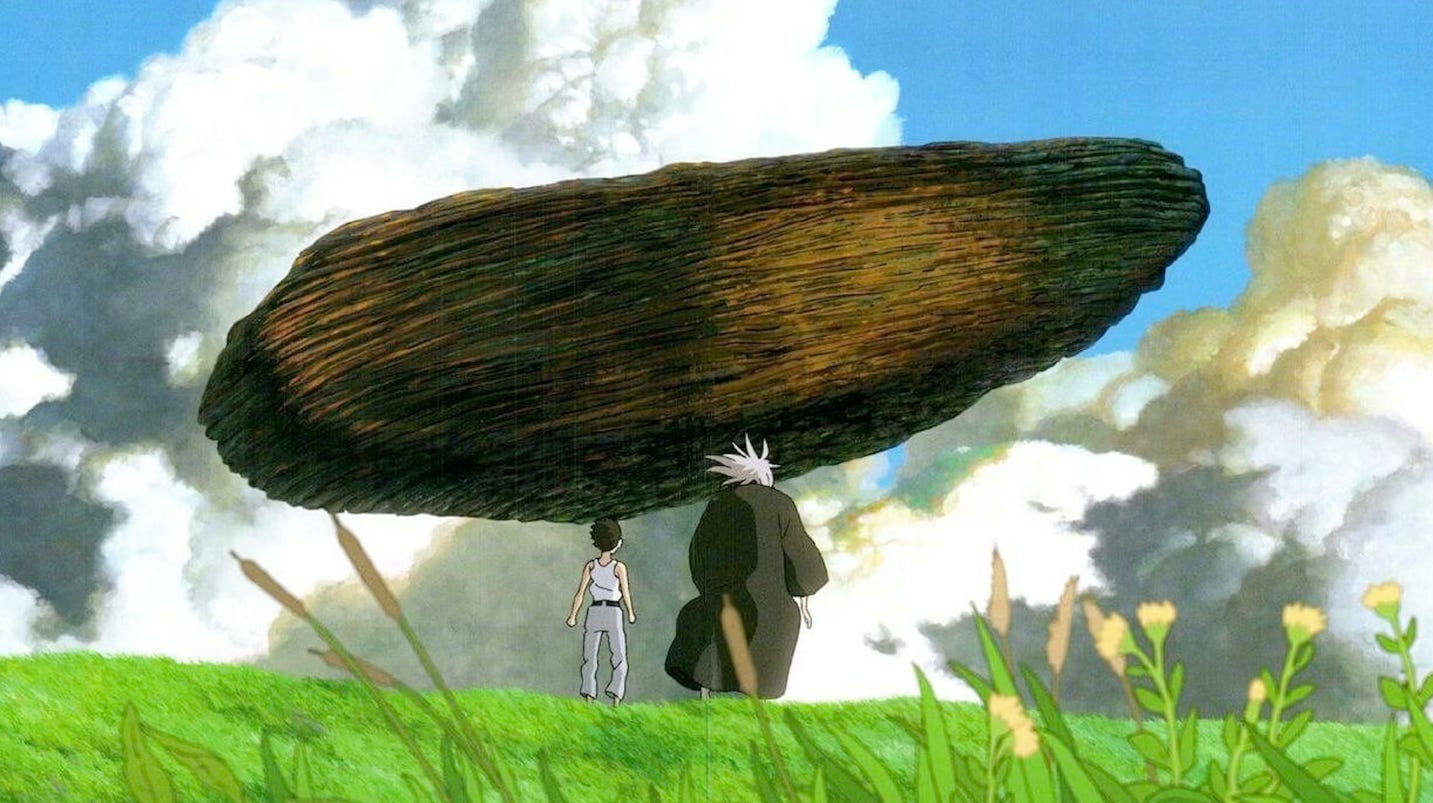

The Boy and the Heron

Dir. Hayao Miyazaki

124 min.

When The Boy and the Heron premiered in Japan this past summer, it arrived shrouded in mystery, sort of. In the lead up to its debut, Studio Ghibli chose not to release a trailer, or even any still images, only a poster illustrated in style that would look nothing like the final film, barring some radical break with the past. The film’s first audiences were greeted by a fantastic trip into a treacherous wonderland filled with strange creatures of shifting loyalties, references to Japan’s World War II past, and a child confronting family upheaval after moving to a new home. In its basic building blocks, it’s exactly what might be expected of a new film by Hayao Miyazaki. But it’s the unpredictable ways that Miyazaki combines those elements that makes it as awe-inspiring and unnerving as any film he’s ever made.

Now 82, Miyazaki announced his retirement after the release of The Wind Rises in 2013. A divisive sort-of biopic of Jiro Horikoshi, an aircraft designer whose work included the fighter planes used in World War II, The Wind Rises doubled as a portrait of a creator disturbed by creations that had slipped away from his dreams of what they could be. It played like an appropriately reflective final film, but the retirement didn’t stick and The Boy and the Heron seems even more concerned with an artist making one last attempt to address his obsessions. It’s tempting to call it Miayazaki’s Tempest, in no small part due to the inclusion of a Prospero-like figure trying to perform the equivalent of breaking his staff and drowning his book. But it’s such a typically slippery Miyazaki work that comparisons don’t stick to it easily.

In 1943, the war has come to Tokyo and, after losing his ailing mother Hisako in a hospital, 12-year old Mahito (voiced in the Japanese-language version by Soma Santoki) relocates to the country where he father Shoichi (Takiya Kimura) can continue his work for the aeronautics industry (the first of many plot details that echo past Miyazaki films and the director’s own life). After taking up residence in a country house tended to by a gaggle of maids led by Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki), he’s bullied by the local boys as he attempts to adjust to his father’s marriage to Hisako’s pregnant younger sister Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura). Mahito becomes withdrawn and develops a cruel streak he directs against a Grey Heron (voiced, in time, by Masaki Suda). But when Natsuko goes missing, Mojito’s search brings him into another world where the Grey Heron and Kirkio both take on new forms and the rules that govern the world they left behind seem not to apply.

Attempting to describe what happens next is to risk running the word count of this review to novel length, if not courting madness. But describing how it feels is easier. The Boy and the Heron is filled with whimsy and wonder placed atop a surface that threatens to collapse them into horror. This sense begins even before Mahito enters the tower. His new house is surrounded by the wonders of nature that contrasts sharply with his roiling emotions. A scene where Mahito attempts to injure himself is played with disturbing realism, and the world he enters frequently reflects his unsettled state. The Gray Heron becomes a taunting antagonist then an ally, but an unreliable one (and one whose body keeps altering form in ways that sometimes reflect this changing state). His guides to the world, including a younger Kiriko and a mysterious woman named Himi (Aimyon) prove as vulnerable to its perils as he is. Wondrously rendered creatures — including a flock of pelicans and some anthropomorphized parakeets — are as threatening as they are beautiful.

None of this is particularly easy to follow, at least on first viewing, and whether there’s any logical consistency to the world of the film is a matter of debate. But if there is, it’s far removed from what makes the film so enchanting and powerful. Of a piece with Miayazaki’s most directly personal works like My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away, The Boy and the Heron similarly draws viewers into a shifting world that takes on the rhythm of dreams and the fuzzy texture of childhood memories, with all their unruly emotions and capacity for outsized wonder and fear. If it proves to be Miyazaki’s swan song, it’s an apt one, and often seems to be designed to serve as such. But since surprise has been central to his art and career, it’s best not to call it that yet.

The Boy and the Heron premieres in theaters tonight. It is being released in both dubbed and subtitled versions. We saw the subtitled version and the voice credits above reflect this. But it’s worth noting that recent dubbed versions of Miyazaki films have been quite good and this one features an intriguing cast that includes everyone from Robert Pattinson (as the Heron) to Dave Bautista (as the Parakeet King).

Finally, thanks to Seth Meyers for the shout-out when talking to Elizabeth Banks on Tuesday night. We like what you do, too.

I already saw the subtitled version of THE BOY AND THE HERON last week (it's truly spectacular), but this Saturday I'm going to see the dubbed version in IMAX as well as POOR THINGS in Dolby! David Ehrlich just published a wonderful article on the dubbing of THE BOY AND THE HERON on IndieWire: https://www.indiewire.com/features/interviews/boy-and-the-heron-english-dub-robert-pattinson-florence-pugh-1234932812/

I loved THE BOY AND THE HERON a lot. At the moment it’s in my top ten films of the year. Just a wonder to behold on the big screen, especially as it appears Miyazaki is as bad at retiring from filmmaking as Steven Soderbergh is.