In Review: 'Licorice Pizza,' 'The Matrix Resurrections,' 'Parallel Mothers,' and 'Don't Look Up'

A holiday review-a-palooza with ambitious new films from big-name directors: Paul Thomas Anderson, Lana Wachowski, Pedro Almodóvar, and Adam McKay.

Licorice Pizza

Dir. Paul Thomas Anderson

133 min.

There’s no narrative arc to Licorice Pizza, Paul Thomas Anderson’s beautiful memory of San Fernando Valley in 1973. Instead there’s a satisfying narrative drift, which is much harder to pull off. There’s a seductive ease to Anderson’s filmmaking that makes the film seem pleasantly minor by comparison to the big swings of Boogie Nights, There Will Be Blood, and The Master. Yet the evocative specifics that create such a dreamy atmosphere—the music, the decor and hang-out spots, the anecdotal pieces of storytelling—belie the difficult work of engaging audiences with characters who are not moving forward, but zigzagging at best. Licorice Pizza may be classified as a coming-of-age story, but the term suggests an evolution that doesn’t interest Andersons here. Uncertainty and stasis are the film’s prevailing conditions, and his task is more about defining them than resolving them.

An important moment comes in first few minutes, when 25-year-old Alana Kane (Alana Haim), working as an assistant for a school picture outfit, gets slapped on the behind by a photographer. She’s repulsed by the gesture, but this is 1973, so she understands there are no repercussions for sexual harassment—it just happens in the flow of the day, so common an occurrence that it doesn’t pause the tracking shot that follows her across the gymnasium. Still, it gets to her, and suddenly the fact that she’d been asked on a date by a 15-year-old, Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman), seems relatively harmless, a relationship that she at least has the power to control. (Or so she thinks.) Given the general contours of her life—a terrible job, no career prospects, still living at home under her father and sisters’ prying eyes—it’s little wonder that she takes the charming young man up on his offer. It’s not like it will ever go anywhere.

The Valley is the main character in Licorice Pizza, which makes it analogous to the hangout vibes of Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time…. in Hollywood, an opportunity for a great California filmmaker to go time-traveling to an era that excites him. There’s not even any era-defining cultural signposts like the Manson murders, and the stars shine no brighter than Jon Peters (Bradley Cooper), whose career as a film producer hadn’t even started yet. (The one firm connection between the two films: Peters learned how to cut hair from a protégé of Jay Sebring, the celebrity hairstylist who was murdered along with Sharon Tate and who’s played in Tarantino’s film by Emile Hirsch.) The oil embargo figures in in a fascinating way, but otherwise, Anderson conceives of the ‘70s Valley as a more laid-back and passive milieu, with a future as up-for-grabs as his characters’ destinies.

In this hazy, golden sandbox, young Gary is king—or at least he has the confidence to assume the throne. He’s a prolific child actor, though there’s plenty of evidence that his moment may be coming to an end. Still, Gary has a showman’s flair that breaks down Alana’s defenses enough to where she grudgingly enjoys being around him, even if she’s teasing him most of the time. His precociousness extends to a talent for entrepreneurship, so when he jumps on the waterbed craze sweeping the country, Gary brings Alana on board as a saleswoman and delivery person. It’s not the last company he launches, either, but Alana naturally eyes better opportunities for herself, like a career in acting or volunteer work on a mayoral campaign. She’s 25. She can’t be doing odd jobs for this twerp forever.

The episodic style of Licorice Pizza allows room for surprising and delightful drive-by appearances from recognizable faces, like Cooper’s amped-up, belligerent Peters, Sean Penn as an aging star who’s clearly inspired by William Holden, and and Benny Safdie as an idealistic candidate with a potentially fatal flaw in his campaign. Much like another fine ‘70s nostalgia piece, Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused, the pleasing texture of Licorice Pizza masks the emotional turbulence under the surface. Anderson and Haim, with her sharp-elbowed and funny yet soulful performance, capture the flailing, directionless condition of being a woman in her mid-20s, which is bad in any period, but bad in many other ways connected to time and place. Her inexplicable relationship with a teenage boy—and let’s please be clear about the very mild boundaries of this relationship—becomes, in this context, quite explicable. — Scott Tobias

Licorice Pizza is currently in limited release.

The Matrix Resurrections

Dir. Lana Wachowski

148 min.

There’s a scene early in the The Matrix Resurrections where Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves), a wildly successful video game designer, sits around a table with his development team to talk about a follow-up to his visionary game The Matrix, which he’d based around his own distant dreams. As Anderson’s minions geek out about the project, they talk about the legacy of this game that has become a cultural phenomenon. How it’s about trans politics. Or crypto fascism. Or capitalist exploitation. And how, if they were to revisit this world, it couldn’t be just another reboot. Welcome to The Matrix: Into the Metaverse.

The ambivalence co-writer/director Lana Wachowski feels about returning to the science-fiction trilogy she wrapped up with her sister, Lilly, nearly two decades ago, is so obvious in The Matrix Resurrections that she’s made it part of the narrative fabric. If you’re asking the questions, “Why another Matrix? And why now?,” rest assured that Wachowski is puzzling over them, too, right out in the open. There are cynical commercial reasons for the project: The Wachowskis haven’t had a hit since the trilogy, only a string of cult items like Speed Racer, Cloud Atlas, Jupiter Ascending, and the Netflix series Sense8. And we’ve entered an era where there’s a dwindling market for any big-budget movie that’s not based on preexisting IP—which, of course, means that the original Matrix would not get made today, but the demand for another sequel is high.

But it would be unfair to assume iconoclasts like the Wachowskis are chasing a quick money grab, as ungainly and superfluous a prospect as a sequel to a trilogy might appear to be. For people across the sociopolitical spectrum, The Matrix was a defining moment, a red-pilled accounting of a world—our world— that felt radically destablized, evolving past the point where it could be controlled—or even understood. There have been indications that the Wachowskis are more sympathetic to the film being embraced as an expression of trans identity than as a touchstone for alt-right dipshits—as evidenced by Lilly’s now-legendary clothesline of Elon Musk and Ivanka Trump on Twitter—but there’s also a general sense that the significance of the trilogy had gotten away from them. A new film could wrest it back, and perhaps become an updated vessel for technical wizardry and philosophical nuggets.

That’s the idea, anyway. The reality seems even simpler: Lana Wachowski loves her characters as much as the films’ admirers do, and wants to see them revived, so much so that this sequel’s dense narrative architecture is built around their reunion. Those other rationales are more thinly supported, as a smattering of fresh insights float around in the film’s conversational soup, and the action sequences mostly evoke a sense of déjà vu, albeit with a notably shocking new element in the grand finale. There’s too much thought invested in creating The Matrix Resurrections to dismiss it as mere fan service, but fans getting serviced is not exactly a minor side effect of the experience, either. The film struggles to justify its existence.

Opening in the cozy, false, lame-o environment of the Matrix, the film finds Mr. Anderson, the man we know as “Neo” or “The One,” leading a simple yet troubled life as a gaming guru. His memories of the world as it really is—the one controlled by the Machines, who extract energy from humans like batteries—have mostly been relegated to dreams that he shares with his analyst (Neil Patrick Harris). But Anderson can’t stop thinking that he recognizes a woman at the coffee shop named Tiffany (Carrie Anne-Moss), who looks like the person we know as Trinity, only she has kids and a dopey husband named Chad. All gets explained when young agents, led by Bugs (Jessica Henwick) and a refashioned Morpheus (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), bring him out of the Matrix and back into the grubbier realm of the truth.

The Matrix Resurrections has a long wind-up before it delivers the pitch, which can’t entirely be blamed on the need to re-acclimate us to a world that took three films and a lot of explaining to establish. Wachowski spends an inordinate amount of time ruminating on her own creation rather than moving it forward to the uncharted territory—which, in its way, puts the film in line with the new phase of Marvel movies like Spider-Man: No Way Home and the paralyzing self-awareness that has gone along with it. But this remains that rarer of things: A personal vision writ extremely large, with a still-singular graphic splendor and juicy themes of identity, consent, and the limits of conspiratorial thinking. Whatever Easter eggs viewers might find here are at least laid by the White Rabbit. — Scott Tobias

The Matrix Resurrections is in theaters everywhere and on HBO Max.

Parallel Mothers

Dir. Pedro Almodovar

120 min.

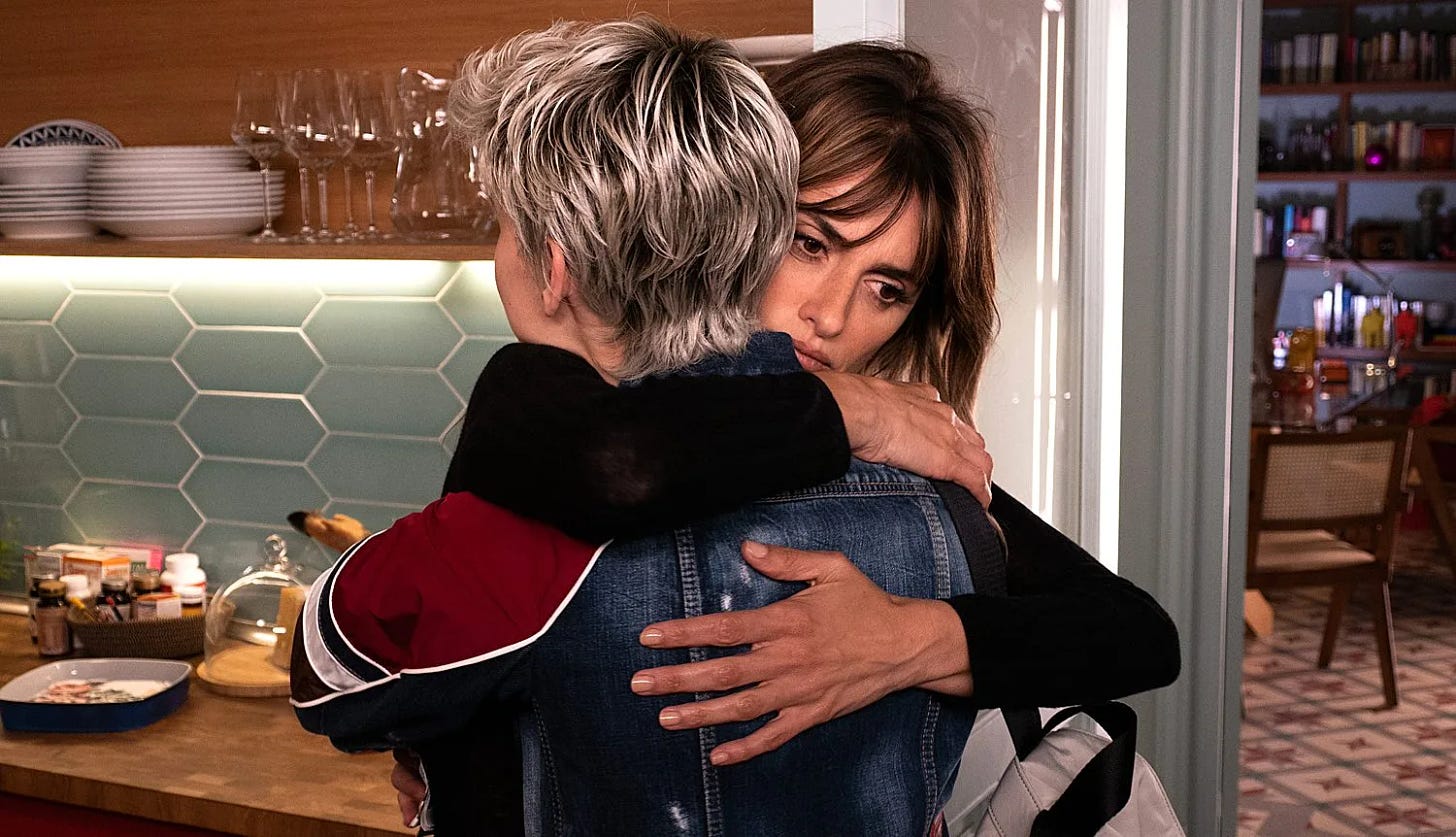

Pedro Almodovar’s Parallel Mothers opens with a series of scenes that, for much of the film, seem to exist mostly to set the plot in motion. In Madrid, successful, single, verging-on-40 photographer Janis (Penélope Cruz) is winding down her latest assignment, a magazine spread on the handsome forensic anthropologist Arturo (Israel Elejalde). After both agree that, yes, posing Hamlet-style with a skull might be a little on-the-nose for the shoot, Janis arranges to him after the shoot about a matter of personal and historical urgency. She wants to excavate a burial site, specifically a location she believes to be a mass grave used to bury her great-grandfather and nine others in the early days of the Spanish Civil War. He agrees because he’s passionate about the cause of unearthing the past (and past crimes). He also likes Janis. They sleep together and, one time leap later, Janis is in a maternity hospital ready to give birth.

It’s here that Parallel Mothers seemingly begins in earnest. That grave, the forces that created it, and the need to dig it up get brushed mostly aside for much of the film. But when they return, it’s a clarifying moment. This is one of Almodóvar’s intimate, tightly focused personal dramas, but one that explores the costs of lies and living in bad faith and the ways such actions, at any level, have long-lasting consequences not always found in history books. The personal is political, and sometimes it’s also politics’ mirror.

Married and unsure about having a child, Arturo remains out of the picture as Janis gives birth, but she’s fine, even enthusiastic, about joining her family’s long line of single mothers. She even makes a friend in the process, Ana (Milena Smit), a younger roommate who’s much less excited about her own impending motherhood. They support each other through the childbirth process, then go their separate ways, at least for a while, as Janis deals with balancing her new responsibilities with her professional ambitions and Ana faces raising her child without the expected help from her mother Teresa (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón), an actress in middle age enjoying her first brush with sustained professional success.

Ana and Janis’s paths eventually cross again, though to explain how, and why they remain in each others’ lives for some time after, is to risk spoiling the heartbreaking= surprise at the center of Almodóvar’s plot. It also risks making Parallel Mothers sound like one of the wild, high-spirited, coincidence-filled melodramas of his early work rather than the more somber, deeply moving melodramas of his more recent career. The film finds a tone almost unique to Almodóvar, one at once romantic and unsettled. His camera is swooping but uneasy, suggesting something upsetting could happen at any moment, even when the drama is purely internal. He can make the story of a moral quandary, which Parallel Mothers eventually becomes, play like a suspense film. (Almodóvar found a keeper of a collaborator when he first teamed with composer Alberto Iglesias in the mid-’90s. His score, which accompanies almost every moment here, mixes romantic themes with unsettling passages reminiscent of Bernard Herrman.)

The cast, from relative newcomer Smit to Almodóvar stock player Rossy de Palma (as Janis’s supportive best friend) is uniformly excellent, but the film belongs to Cruz. Her eighth collaboration with Almodóvar centers on a performance as powerful as any that precede it. Janis begins the film as a woman confident she has the world figured out only to find her notions about herself, her capabilities, and what she believes challenged by becoming a mother. Through it all, Cruz maintains the melancholy air of a woman who feels the weight of history settling on her, only to learn she has her own choices to make about what that history means, and how it might reshape the future. —Keith Phipps

Parallel Mothers is currently in limited release.

Don’t Look Up

Dir. Adam McKay

138 min.

Early in Paul Schrader’s 2017 film First Reformed, troubled pastor Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) attempts to counsel Michael (Phillip Ettinger), a parishioner so concerned with the effects of climate change he lives on the brink of madness. In one of the most harrowing scenes in recent memory, Michael uses video clips and scientific data to show just how profound humanity’s damage to the Earth has become, lamenting how little is being done to reverse that damage (in fact, quite the opposite), and concluding that it’s almost certainly too late to avert catastrophe. It’s terrifyingly persuasive, both as an info dump about the climate crisis and as a depiction of how, living with this knowledge, there’s little most of us can do but scream at the heavens or fall into despair..

Directed by Adam McKay from a story he conceived with journalist and political commentator David Sirota, Don’t Look Up attempts to create the comedic equivalent of that scene at feature length, which is both its most daring quality and the reason it never quite works. It’s satire fueled by anger and terror, but the comedy muffles the arguments when it should enhance them, and an air of gravity keeps a cap on the laughs. McKay attempts to create a contemporary combination of Dr. Strangelove’s dry, merry cemetery polka and the rapier precision of Network (one character even gets the equivalent of the monologue that won Beatrice Straight a Best Supporting Actress Oscar). But it never reaches the heights of either, mostly playing like a sketch idea stretched out to puff pastry thinness until it gives up and just waits for the Earth to burn.

That its central metaphor gets increasingly less clever as the film goes along doesn’t help. Don’t Look Up contains no direct references to climate change, instead subbing in the imminent arrival of a previously unknown comet that’s—shades of Melancholia—on a collision course with Earth. First discovered by Michigan State doctoral candidate Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence), during a late-night session with a powerful telescope, its threat becomes obvious and undeniable after her supervisor Randall Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) crunches some numbers. In six months, the comet will plunge into the Pacific Ocean, doing irreparable damage to the Earth and all who live there. Armed with that knowledge, Kate and Randall, with some help from a government scientist (Rob Morgan), try to get the message out and put a plan in place to avert disaster. But waking up the world to an imminent extinction level event isn’t as easy as it sounds.

Don’t Look Up is sharpest early, which allow McKay to send up both the current state of American politics and the overcrowded media landscape. President Janie Orlean (Meryl Streep), a Trumpian weirdo demagogue who’s made her son (Jonah Hill) her Chief of Staff and nominated her celebrity sheriff/ex-porn star lover to the Supreme Court, doesn’t see much of an angle in alarming everyone (at least until after midterms). An attempt to leak the news to the media proves difficult, too, the urgent message all but drowned out by the relentless cheer of a pair of morning show hosts played by Tyler Perry and Cate Blanchett (chillingly believable as a smart woman who’s subsumed all the parts of herself that don’t serve the role of a basic cable news blonde). It’s enough to drive Kate to scream a “We’re all going to fucking die!” warning in frustration. When she does, she becomes a meme.

Don’t Look Up begins as an unsubtle but mostly effective send-up of how hard it is to get anything done, or any message heard, no matter how urgent the need, particularly in a moment of ridiculous politics and social media-distorted information (and misinformation). Then it keeps circling around to make the same points over and over while bringing in the occasional new element, like a tech billionaire (Mark Rylance, more or less speaking in the same voice he used in Ready Player One) who senses opportunity in the oncoming death comet. As a comedy, it exhausts itself quickly, and the broadness of its premise makes its more grounded, trenchant attempts at satire feel out of place. In its final stretch it settles into mostly being a straightforward, heartfelt disaster movie, one highlighted by a late-arriving Timothée Chalamet as a surprisingly soulful Gen Z skater dude. Why? By that point it just seems like McKay is trying to push every idea he can into the already overstuffed film.

After finding success with comedies like Anchorman and Talladega Nights, McKay kicked off a new phase of his career with the comedy-and-current events mix of 2015’s sharp The Big Short. But, with Vice and now this, his skill at combining the two has slipped since that first attempt. Neither are entertaining or cutting enough to be effective, as comedy or commentary. Don't Look Up has something urgent to say but, in a twist straight out the film itself, it can’t package its message in a way slick or entertaining enough to make many likely to listen. —Keith Phipps

Don’t Look Up is in limited release and will be on Netflix starting December 24th.

I caught Don’t Look Up at the Alamo Drafthouse last week, and if anything 2.5 stars is generous. Social satire is tricky, because it needs to be absurd while still having characters behave in a fundamentally believable way. I didn’t believe 90% of what the characters in Don’t Look Up did. Do I believe that some people would live in denial? Sure. Do I believe that literally no one would take this seriously, including the New York Times? No.

It felt less like a coherent movie and more like McKay’s frustration about covid and climate change devolving into a rant. I get it, I’m frustrated about those things too, but watching this movie was a bit too much like that one friend’s Facebook profile that is nothing but angry political links, memes, and commentary.

On a more positive note, can we talk about how wonderful Nightmare Alley was?

RE Licorice Pizza -- I think the film has more of a narrative arc than people give it credit for. Throughout the story, Alana feels like Gary lowers her social cred, so keeps looking for higher and higher status men and careers to make her feel valuable. Gary counters this by trying to raise his own status through his antics and business ventures. When Alana finds out how Benny Safdie's fear of losing face ruins a relationship with someone he loves, Alana realizes that she's essentially doing the same thing. Gary sees this for himself when Alana's missing from the pinball palace's opening night. And that's what makes the climax such a beautiful thing.