In Review: 'Eternals,' 'Spencer,' 'Finch,' and 'The Beta Test'

In this week's reviews, the most beautiful MCU is also the worst, Pablo Larraín gives Princess Diana the 'Jackie' treatment, and robots and agents run on faulty programming.

Eternals

Dir. Chloe Zhao

156 min.

Eternals is the most beautiful movie made as part of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. It’s also the worst. That might sound like a contradiction, but previous contenders for the dubious honor of the MCU’s lowest moment—Iron Man 2, say, or Thor: The Dark World—are at least fully functional Marvel movies.They're weak but functional cogs in a big entertainment machine, made up of the same appealing elements as the better cogs: winning characters, witty exchanges, plots that roll along at a steady pace, and forgivably bleh action climaxes. Eternals is something else. It’s sweeping in scope—essentially spanning the whole of human history and then some—and filled with striking vistas (even if they almost feel pre-fabricated to populate the #OnePerfectShot hashtag). But it’s also a slug of a movie, a shapeless, poky thing that just kind of sits there threatening to stir to life every once in a while but then collapsing as it grinds to a climax in which our heroes must, yawn, save the world.

The trouble begins, but doesn’t end, with those doing the world-saving. The Eternals were created by Jack Kirby during his much-heralded return to Marvel in the mid-’70s, which followed his much-heralded defection from Marvel to DC in the early-’70s. During Kirby’s time at the distinguished competition, his interests shifted away from earthbound superheroes and toward cosmic, godlike characters of the sort that had begun appearing with increasing frequency in his Fantastic Four work. At DC that took the form of his Fourth World mythology. Kirby’s Eternals found him working in in a similar vein at Marvel via stories of superpowered, virtually immortal protectors of humanity deposited on Earth millenia ago by the seemingly all-powerful extraterrestrial Celestials—a bit of pseudoscience inspired by the dubious bestseller Chariots of the Gods?

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

The shift resulted in some of Kirby’s most ambitious, experimental work. It also revealed that much of the quirky personality, and virtually all of the humor, of his Marvel work came from writer Stan Lee, with whom he shared an uneasy but creatively fruitful partnership. It’s no coincidence that the Hulk and Thor became pop culture icons while Machine Man and Black Racer became cult heroes to hardcore fans. It’s also why the Eternals—which inspired some of his most visually spectacular and narratively stolid work—have until now remained confined to the comic book page.

In that respect, Chloe Zhao’s take on the characters keeps with the tone of Kirby’s work. It’s a stunning looking film filled with atmospheric shots of forbidding forests and sweeping plains bathed in magic hour glow that’s about as dramatically gripping as a multi-paragraph Wikipedia plot summary. At the center of a sprawling cast, Gemma Chan and Richard Madden play, respectively, Sersi and Ikaris, a couple whose on-again/off-again relationship has spanned millennia as they have driven off foul, animalistic villains called Deviants whenever they’ve threatened humanity. But, in the present day, the Deviants have seemingly been pacified for centuries and Sersi and Ikaris have drifted apart. So, for that matter, have the other Eternals, most of them wandering to one corner of the globe or another and blending in with humanity as they pass the time. These include the powerful (even by Eternals standards) Thena (Angelina Jolie) and group leader Ajak (Salma Hayek), the sole member with a direct line to their Celestial bosses.

It’s tempting to blame Chan and Madden for the film’s terminal dullness since they display so little charisma and generate even less chemistry, despite figuring in the MCU’s first proper love scene (a dead-faced, above-the-shoulders, some-mild-thrusting-implied moment that will go over kids’ heads and leave grown-ups wondering why such perfect creations have such uninspired sex). That Jolie and Hayek fare no better with the material suggests deeper problems. The script, credited to Zhao, Patrick Burleigh, Ryan Firpo, and Kaz Firpo, hinges on a major, and pretty clever, twist but takes forever to pick up any momentum as it flashes from the present to several episodes in the Eternals’ past. It’s also, for the most part, fatally sparkless. By an hour in it’s hard not to be starved for a line like “That’s America’s ass” or a reference to The Empire Strikes Back being a “really old movie.”

The exceptions come from Kumail Nanjiani, who livens things up as Kingo, an Eternal who’s remade himself as a Bollywood star, and Brian Tyree Henry, who brings emotional heft to his work as Phastos, the Eternal whose mechanical genius has helped humanity develop over time. Henry conveys a sense of regret deep enough to lead him to flee into the arms of humankind. (He’s also married to and raising a child with a man, a relationship the film treats with admirable matter-of-factness. Credit where it’s due, it’s another, and better executed, expansion of the MCU’s idea of sexuality.) Such exceptions, though, prove brief and rare. The plot doesn’t waste much time before stranding both characters at the edges of the action.

That leaves room for a lot of superpowered energy blasts and a desperate scramble to stop the world from ending: an MCU movie, in other words, just not a particularly engaging one. And not, when measured against films like The Rider and last year’s Best Picture-winning Nomadland, much of a Chloe Zhao film. Zhao’s love of landscapes remains evident, as does her love of dwarfing her cast within those landscapes to suggest the tininess of a single life when measured against the vastness of the world around it. Eternals allows her to pan out even further, to the whole cosmos, but unlike before, she seems to lose sight of whatever interested her in her characters. They talk and occasionally brood but, like Eternals itself, they mostly seem to be marking time between action scenes, scenes that play out much like those found in other MCU movies that don’t look nearly as warm on the outside but also don’t feel so dead in the middle. —Keith Phipps

Spencer

Dir. Pablo Larraín

111 min.

It’s Christmas weekend at Sandringham Estate and Princess Diana is late again. She’s later than Charles, her mirthless fop of a husband, which was to be expected. But she might be later than the Queen herself, which ranks high on the endless list of traditions that Diana so casually violates, along with more obscure transgressions, like altering the order in which she wears the dresses that have been chosen for her or balking at having her weight checked before the holiday. (That last one is done as “a bit of fun,” she’s told, because guests often gain a few pounds in indulgent meals and desserts. It’s less fun for a highly scrutinized royal with an eating disorder.) Diana has a decent excuse for being late this time—she’s genuinely lost, even though she’s from the area—but she’s also chosen to break away from her security detail and drive herself. The wheels are, at least figuratively, coming off.

Written by Steven Knight and directed by Pablo Larraín, Spencer feels in every way like a companion piece to Larraín’s Jackie, both mesmeric suites about women trapped in a gilded cage of politics, privilege, and intense media scrutiny. Between both films’ compressed, moment-in-the-life approach to biography, interest in fashion as statement, spare string-based score (Mica Levi in the earlier film, Johnny Greenwood here), and a style that emphasizes long tracking shots, centered framing, and a shallow depth-of-field, this starts to look like a repeatable template. Or, at a minimum, they suggest an argument that the histories of certain public women tend to rhyme or repeat themselves.

There’s a one-size-fits-fall quality to Larraín’s direction that diminishes Spencer in comparison to Jackie, along with a scenario where the stakes are simply not as consequentially high. In Jackie, Jacqueline Kennedy had to swallow her grief and handle the nation’s business on November 22, 1963, all while wearing a pink suit still stained with her husband’s blood. That tension between civic duty and swallowed grief isn’t matched in complexity by Diana’s Christmas weekend with a quietly hostile royal family, but Spencer is nonetheless an experience of visceral, suffocating intensity. She is a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown, and most of the family, along with the largely invisible press, seem intent on hastening her collapse.

No doubt summoning her own experience as a relentlessly scrutinized celebrity, Kristen Stewart disappears completely into the role of Diana, playing her as a woman fighting a quixotic battle against centuries of hidebound tradition and the people determined to hold her to it. The year is 1991, a decade into a marriage with Prince Charles (Jack Farthing) that’s gone sour on rumors of an affair and possible divorce, but yielded two sons, William (Jack Nielen) and Harry (Freddie Spry), to whom she’s immensely devoted. In the film’s imagining, the rituals and duties of being a princess have no benefit to Diana, so she bucks against them at every opportunity, all while reflecting on her nearby birthplace, a boarded-up property that suggests a more carefree past and a road not taken.

From the opening sequence, which details the military rigors of simply setting up Sandringham’s kitchen for the weekend—the crates of produce and lobster look like the metal housing of RPG launchers—Spencer establishes a sense of established ritual and order that Diana simply doesn’t care to respect anymore. Why should she have to weigh herself? Why won’t someone turn up the heat? Why are her dresses picked out for her like a child? Why do her kids have to open presents on Christmas Eve instead of Christmas morning, as they’d prefer? There’s no flexibility on any of these matters, no matter how small the accommodation would be, and her rebellion is met by a passive hostility that feels conspiratorial because it almost certainly is. When it becomes too obvious that Diana confides in her dresser (Sally Hawkins), the woman is swiftly reassigned.

Spencer lays it on too thick at times, like bringing in the ghost of Anne Boleyn as a reminder of what happens to women who step out of line. Beheadings can still occur in England in 1991, just not literally. Better are performances by Timothy Spall as Equerry Major Alistair Gregory and Sean Harris as head chef Darren McGrady—the first a cold administrator of tradition, whose advice to Diana slips contempt into royal deference, and the second a sympathetic ear, who wants to make her life easier. The finely wrought script, by Steven Knight, adds these subtle character notes to deepen what might have been a narrow portrait of a princess under duress. Otherwise, the film might be Bambi meets Godzilla, an innocent crushed by a properly wielded soup spoon.

Like Jackie, Spencer is about a woman pressing against the limits to her own agency, walled in by her relationship to a hounding press and unyielding institutions. The difference is that Jackie feels heroically duty-bound to respect the processes that hold American democracy together while Diana wriggles under the arbitrary strictures that punish her every time she steps out of line. She wouldn’t divorce Charles until five years later, and then she died in a car accident a year after that, but there’s a kind of death already hanging over Spencer’s 1991, a presaging of certain tragedy, hastened by a class of buttoned-up co-conspirators. In Larraín’s admiring portrait, she goes down fighting. —Scott Tobias

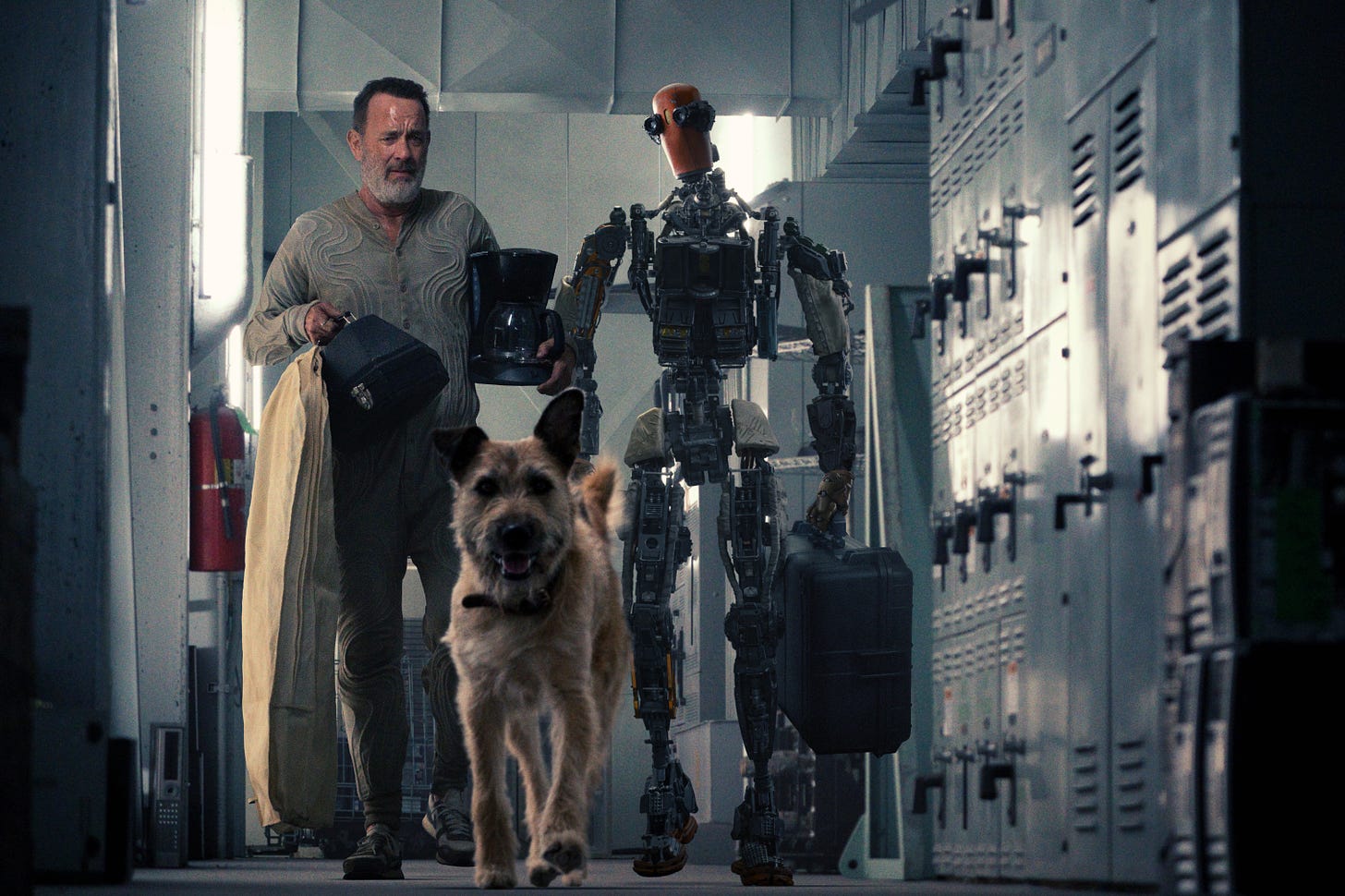

Finch

Dir. Miguel Sapochnik

115 min.

Tom Hanks is never the problem. One of the world’s most beloved stars, Hanks has reached a stage of his career where he can pick and choose to appear in whatever he likes. And, because he has good taste, he usually ends up mostly appearing in pretty good, occasionally great, movies. Usually. But even in a dud like The Circle, which found him taking on a rare villainous role, Hanks does thoughtful work. He’s always fully there and doing his best. That’s the Tom Hanks way. That’s true of Finch, too, in which Hanks plays a quintessentially Hanksian character: a man whose innate decency can’t be dimmed even by the apocalypse.

Directed by Miguel Sapochnik (Repo Men, a bunch of Game of Thrones episodes) from a script by Ivor Powell, Finch begins promisingly enough with scenes of Finch (Hanks) patrolling a decimated American heartland in search of scraps of food. An environmental catastrophe, we’ll soon learn, has turned the ozone layer into, in Finch’s words, “Swiss cheese,” making even a few moments of contact with direct sunlight akin to stepping into a laser beam. Still, Finch has survived in an underground bunker that doubles as a lab, living a quiet life with his dog as he scans books and tinkers with robots. He knows it can’t last, however, and when he builds an android who chooses to call himself Jeff (voiced by and performed in motion capture by Caleb Landry Jones), he sets off for the West Coast.

Finch’s problems build from there, as do the film’s, which eventually explains why Finch created Jeff but never why he programmed his robot companion to be a bumbling idiot with a tenuous grasp on the English language and a seemingly irresistible urge to engage in comical hijinks, sort of a cross between Balki Bartokomous, Jar-Jar Binks, and Roger Rabbit. Jeff’s an annoyance who takes over the movie, transforming what begins as a study in loneliness and isolation into an alternately goofy and cloying trip through the wasteland. Hanks is fine, particularly when delivering a flashback-accompanied soliloquy about how humanity turned on itself as the catastrophe mounted. But Hanks is always fine. It’s the rest of Finch that’s the problem. —Keith Phipps

The Beta Test

Dir. Jim Cummings and PJ McCabe

93 min.

“I’m excited. Let’s keep talking.” These words are like a mantra for Jordan Hines, a Hollywood agent whose toothy enthusiasm reads as barely concealed derangement, like a salesman who never makes a deal, but has to keep acting, against all rational thought, like he could secure a deal in the future. As played by Jim Cummings, the co-writer and co-director of The Beta Test, Jordan is parody of Type-A personalities, resembling Patrick Bateman in American Psycho if he was less successful and merely starting on the pathway to murderousness. A man who spends his days genuflecting before disengaged would-be clients while trying to package deals like “a Caddyshack reboot with dogs” has to go a little mad sometimes.

Jordan’s erratic behavior is completely in step with The Beta Test itself, an unstable and unfocused satire that dabbles haphazardly in issues of masculinity, temptation, digital identity, and reformed workplaces but does so with a brio that keeps it on edge. The central intrigue turns on a mysterious purple envelope that Jordan receives as he’s preparing to marry Caroline (Virginia Newcomb), his extremely patient fiancée. The envelope contains an invitation to a no-strings-attached sexual encounter at a hotel, and, much like a wedding invite, offers a menu of options, just for kinks rather than entrees. Jordan follows through on the tryst, blindfolded, but then later realizes, as things get complicated, that he needs to learn not just this one-time partner’s identity but also that of the people behind this odd enterprise.

Both mysteries are unraveled to disappointing effect, but Cummings’ performance as Jordan, along with McCabe’s straight-man routine as his saner colleague and friend, is so bizarre and fitfully hilarious that getting to the end is a great deal of fun. Jordan’s dopey relentlessness as a dealmaker bleeds over into his amateur sleuthing, where he routinely presents himself as a police detective, believing that loud confidence will compensate for his lack of a badge. He gets away with it about half the time—and so does the movie. —Scott Tobias

Thanks for putting The Beta Test on my radar! I liked Thunder Road and Jim Cummings seems like the sort of independent voice I want to support. Sounds like it might make a nice nightcap.

Also, if you're looking to flesh out the Darren McGrady character, the real Darren McGrady has a YouTube channel (featuring clips like "The Royal Chef makes Gumbo - Is It British?" and "You won't believe how The Queen eats pineapple... and other fruits")... I can't go so far as to recommend, but there was one shameful evening where I found him pleasant enough to watch more than I'm willing to admit.

"a cross between Balki Bartokomous, Jar-Jar Binks, and Roger Rabbit" is a hell of a painfully vivid description. Can't help but think that while there is no way I'd enjoy that, it's an interesting stretch for Caleb Landry Jones.