In Review: 'A Haunting in Venice,' 'Dumb Money,' 'Cassandro'

Branagh takes on Agatha Christie (again), Craig Gillespie revisits the GameStop stock rush, and Gael Garcia Bernal dons tights and make-up in a Mexican wrestling biopic.

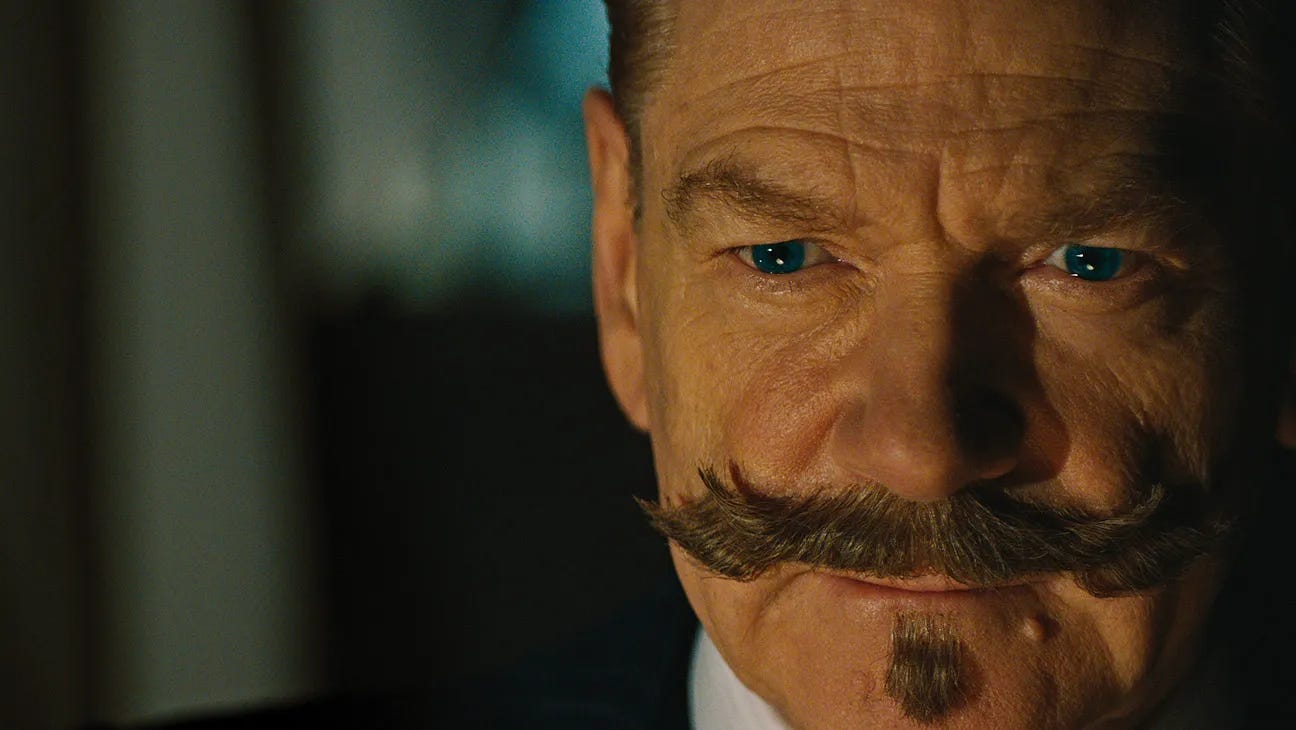

A Haunting in Venice

Dir. Kenneth Branagh

103 min.

When Kenneth Branagh burst onto the scene with Henry V in 1989, critics greeted him like Laurence Olivier’s heir apparent, a 29-year-old director/star who would be the keeper of the Shakespeare flame and give a platform to multiple generations of great British actors. Then he followed it up with the thriller Dead Again, a half-deranged exercise in style that ported over some of his actors (Emma Thompson, Derek Jacobi and, of course, himself), but seemed like the work of another filmmaker. et, there’s a unifying component that’s carried over for the rest of his career, which has still occasionally (if mostly unsuccessfully) dipped into Shakespeare: Branagh is a showman. Often a bit of a ham. And perhaps not the deepest thinker on the classics.

That’s the best way to approach Branagh’s diverting, superficial trilogy (and counting) built around Agatha Christie and her Hercule Poirot character, which started with 2017’s Murder on the Orient Express and has continued with last year’s pandemic-delayed Death on the Nile and the new horror/suspense hybrid A Haunting in Venice. They have all been star-packed whodunits—though the new one has notably fewer big names—but Branagh has consistently sucked up every bit of oxygen as Poirot, the sleuth whose OCD habits (he measures his morning eggs) alert him to the minute signs of criminal mischief. It often feels like the drama between the other characters is an elevated form of pre-performance chatter, as if they’re waiting around for the big show. And then Poirot wows the audience by sawing one of them in half.

A Haunting in Venice is ever-so-slightly worse than the other two, because Branagh gets carried away trying to turn a spooky palazzo into a Don’t Look Now for jump-scare aficionados. Based loosely on Christie’s 1969 novel Hallowe’en Party and set entirely over Halloween night in 1947 Venice, the film stars a conspicuously era-inappropriate Tina Fey as an author who convinces Poirot to attend a seance, where an opera singer (Kelly Reilly) is attempting to contact her dead daughter. The author wants Poirot to prove that the medium for the seance, played by Michelle Yeoh, is a fraud, because it’s been exceedingly difficult for skeptics to see the strings. But unmasking the medium becomes less of a priority once the ritual is started and someone at the party winds up dead.

It does not serve Branagh’s purposes well that his Poirot franchise is running concurrently with the Knives Out movies, which are also twisty, star-laden entertainments, but orchestrated with far greater wit and thematic purpose, along with a more generous survey of the cast. Aside from Yeoh, the cast in A Haunting in Venice doesn’t make much of an impression, ceding the floor to Branagh’s colorful gesticulating on screen and his flashy pirouettes behind the camera. And yet a showman’s a showman: Branagh again throws caution to the wind with his Belgian accent—though his sublimely ridiculous Russian in Tenet is hard to top—and it remains a minor pleasure to watch him hold court, picking at a boot-scuff or some behavioral hitch to catch what others cannot. But when the parlor trick is over… poof, the film disappears in a cloud of smoke. —Scott Tobias

A Haunting in Venice opens in theaters tonight.

Dumb Money

Dir. Craig Gillespie

104 min.

Back in the mid-to-late aughts, when faster internet speeds made day trading a viable (and often calamitous) form of home investment, a friend of mine once explained to me why he bought stock in companies like K-Mart, which had seen better days. He said he liked the underdogs. He identified with them. He seemed to have some counterintuitive sense that all these stocks needed was the faith denied to them by the dark forces of fate and conventional wisdom. As their fortunes turned around, so would his.

Perhaps needless to say, he lost all his money in the stock market. But he was not—and is not—alone in believing that the deck is stacked against the little guy, who are usually chum in shark-filled waters. The brisk, entertaining Dumb Money recalls, with all the meme-crazy irreverence it can muster, the odd moment in pandemic history where my friend might have made a fortune. In a Reddit-fueled frenzy that climaxed in January 2021, retail investors—the “dumb money” of the title—banded together on platforms like Robinhood, a clickable small-money stock app, to boost GameStop, the struggling video game chain, as massive hedge funds were betting on its failure. This David vs. Goliath battle culminated in a short squeeze that captivated the internet and exposed longstanding imbalances in the stock market.

The most template for Dumb Money is The Big Short, another zippy piece of populism that puts the inequities of capitalism in layman’s terms—which is exactly what Wall Street titans count on ordinary people not to be able to do. If you don’t know what collateralized debt obligations or mortgage derivatives are, then you won’t know where to direct your ire about your pension suddenly evaporating or your home loan going underwater. The stakes are not as high in Dumb Money, but the principal is the same: Retail investors are not capable of outmuscling hedge-fund billionaires with the technology, capital, and political connections to swat them like gnats. The GameStop short squeeze is the rare exception, and even that got more than a little dodgy.

Director Craig Gillespie has a soft spot for little-guy schemes, as evidenced by I, Tonya and the miniseries Pam and Tommy, and he keeps his foot on the accelerator, even if that means speeding past any deeper insight into a most cartoonish set of characters. The self-effacing, cat-loving pirate behind the GameStop movement is Keith Gill (Paul Dano), a low-level financial analyst from Brockton, Massachusetts who notes the proliferation of short positions on the stock and feels the company is undervalued. When he starts posting his rationale online, particularly in the popular subreddit r/wallstreetbets, he gains more and more traction and the stock price rises, thanks in part to the ease of the app Robinhood. The spike starts to alarm hedge funders like Gabe Plotkin (Seth Rogen) and Ken Griffin (Nick Offerman) who are used to vacuuming up “dumb money,” and expect to win in the end.

Dumb Money surveys an ensemble full of working-class investors, including a nurse (America Ferrara), a GameStop clerk (Anthony Ramos), and even Gill’s stoner brother (Pete Davidson), who does DoorDash deliveries and still lives with their parents. Most of the action takes place before the COVID-19 vaccines became available, so Gillespie and his screenwriters, Lauren Schuker Blum and Rebecca Angelo (working from Ben Mizrich’s book The Antisocial Network), lean into the notion that these “essential” workers are forever at the short end of the stick. Gillespie doesn’t make the point subtly, and his tendency to overload the soundtrack with pop music, as he did with Cruella, has the effect of reducing human foibles to a series of snappy montages. Yet Dumb Money is irresistible all the same, a rousing tale of economic mischief that makes market shenanigans graspable enough to be enraging. That’s a public service. — Scott Tobias

Dumb Money opens in theaters tonight.

Cassandro

Dir. Roger Ross Williams

107 min.

Even as Cassandro opens, Saúl Armendáriz (Gael Garcia Bernal) is no stranger to being jeered. A native of El Paso, Texas, he regularly crosses the border to Ciudad Juarez to wrestle in lucha libre matches as “El Topo” (“The Mole”), a masked heel whose name refers to Saúl’s diminutive stature. A low-level luchador accustomed to performing before sparse crowds in rings built in the backrooms of auto garages, he mostly serves as cannon fodder for the circuit’s bigger names (and bigger bodies). But Saúl knows he’s capable of more, as does Sabrina (Roberta Colindrez), a fellow wrestler who agrees to train him. She also suggests an image change.

Based on the real-life Armendáriz’s story, Cassandro follows Saúl as he rises through the luchador ranks as “Cassandro,” a persona defined by his effeminate mannerisms and impish taunting of hulking masked opponents flustered by his flirtatiousness. There’s some important context here: Cassandro isn’t a radical break from lucha libre’s past. The stock character of the exótico—mincing gay caricatures in outrageous outfits that mix tights with drag—had been a fixture for decades when Armendáriz introduced his take on the tradition. They were also bad guys, and usually played by men who insisted they were straight. Saúl, who’s made no attempt to stay in the closet, wants to play Cassandro as the hero. (Like most aspects of the film, it’s a streamlined and simplified version of Armendáriz’s biography.)

It’s easy to imagine Cassandro taking the form of an inspirational sports movie in which a tenacious hero’s bravery changes the sport by pushing through the boundaries of prejudice and Roger Ross Williams’ film is that, but only in broad strokes. In perfect sync with Bernal’s performance, its melancholy atmosphere serves as a counterpoint to its triumph-over-adversity narrative. The ballast to Saúl’s ambition goes beyond crowds conditioned to shout homophobic insults at the exóticos. He has a secret romance with a closeted and married luchador (Raúl Castillo) and a close but intense and complicated relationship with his mother Yocasta (Perla De La Rosa), who accepts his sexuality but also still blames it for driving his father away.The film is frank about the cumulative psychic toll of it all and about the grimier side of lucha libre, with its under-the-table deals and late nights extended by copious amounts of cocaine. The film’s a bit unwieldy at times, particularly a largely extraneous subplot involving Bad Bunny as a lucha libre-adjacent drug dealer, and though the film deserves credit for stretching beyond its big climactic match, it lasts at least one scene too long. But Cassandro is a never less than fascinating, and often moving, tour of the lucha libre world as it adapts to changing times, built around a remarkable lead performance. Bernal performs a surprising amount of the wrestling action himself, but it’s his depiction of Saúl as a man whose happiness when not wrestling rarely only rarely pushes beyond the bittersweet that makes the character so haunting. As Cassandro, Saúl may be the one getting picked up by brutes in the ring but he’s always the one doing the heavy lifting. —Keith Phipps

Cassandro arrives in theaters tomorrow. It will be available via Prime Video on September 22nd.

Three awesome, well-written reviews this week guys. I especially love Scott's assessment of Branagh's Poirot project and his screen persona overall.

I loved Branagh‘s Much Ado About Nothing. I thought he and Thompson absolutely nailed it.

It’s the only Shakespearean comedy that I actually enjoy, though. I’m way past the age where I feel the need to pretend that A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a lot of fun to watch for the thousandth time. Fuck Puck.