In Review: 'A Complete Unknown,' 'Babygirl,' 'Nosferatu'

If you had a musical biopic, an edgy erotic drama, and a vampire movie on your holiday wishlist, all your wishes are about to come true.

A Complete Unknown

Dir. James Mangold

141 min.

It’s impossible to make a musical biopic, particularly about an artist as complicated and influential as Bob Dylan, without some streamlining. Sometimes that involves a bit of poetic license that captures the essence of the events being portrayed while fudging the details. Other times it means simplifying moments to the point where any claim of depicting history gets lost and the “print the legend” impulse takes over. A Complete Unknown often plays like a battleground between these two approaches. James Mangold’s new biopic depicts Dylan’s career from his arrival in New York as an ambitious young musician with little more than a guitar and a shaggy head of hair to his name through his controversial electric set at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. It’s a complex, thoughtful, shaded film fighting an ultimately losing battle against mythmaking conflation, a struggle that climaxes the moment when Dylan takes a dramatic beat to pause and consider whether to grab an acoustic or electric guitar before taking the stage.

A Complete Unknown ends with a reinvention but it begins with one, too. After Robert Zimmerman, a middle-class Jewish singer from Hibbings, Minnesota, arrived in New York in 1961 he’s able to remake himself as Bob Dylan, a musical vagabond with a self-invented past that includes references to time spent working in a circus. He seeks to find a spot for himself in the Greenwich Village folk scene, but any hope for success comes coupled to a desire to do right by the musicians who inspired him to travel there in the first place. None were more influential than Woody Guthrie. His struggles with the neurodegenerative condition Huntington’s diseases robbed him of his voice and confined him to a hospital where Dylan made a pilgrimage to pay his respects.

There’s a kind of magic to the depiction of their first meeting in A Complete Unknown. However fictionalized, the film plays the meeting as anything but mythic. Dylan (Timothee Chalamet) arrives as a shy, awestruck kid. Guthrie (Scoot McNairy), though unable to speak, is clearly grateful for the company. And another visitor, Pete Seeger (Edward Norton), acts first as an intermediary then, after the visit ends, as a kind of father figure to Dylan, whom he brings home and feeds and whose music he begins championing. A quiet, deliberately paced sequence earnestly played by all involved, it reworks details covered in every Dylan biography into an understated human drama.

It’s in these moments that Mangold’s film most resembles its source material, Elijah Wald’s 2015 book Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties, which offers a sweeping look at the lives of Dylan, Seeger, the early 1960s folk scene, and what was gained and lost in the moment Dylan plugged in to play before a hostile crowd. Co-written by Mangold (who helped invent the modern music biopic with Walk the Line) and Jay Cocks, A Complete Unknown never fully lets go of its historical ambition but it starts to lean on the familiar biopic elements more and more as the story progresses.

Even at its most rote, A Complete Unknown has much to recommend it. Mangold remains a first-rate craftsman and, as with Walk the Line,the attention to period detail feels transporting. Norton exudes heartbreaking warmth and earnestness as Seeger while both Elle Fanning (as Sylvie Russo, a renamed and slightly fictionalized version of Suze Rotolo) and Monica Barbaro (as Joan Baez) refuse to let their characters be just the women on Dylan’s arm. And, given the seemingly impossible task of playing a figure defined by enigma, Chalamet finds a way to depict him as both a genius of piercing insight and a sometimes snotty, sometimes confused, often opportunistic artist who finds himself with his hands on the levers of history.

Maybe it’s apt that a film about surrendering to distortion and noise would have a clearer sense of purpose in its early scenes than its later ones, when a feeling of “you are there” gives way to “here’s what happened.” The back half of A Complete Unknown lets a recounting of all the big Dylan moments take the place of the story it first sets out to tell at the expense of some of the characters—like Seeger and Russo—key to its telling. Fame and restlessness lead the Dylan of A Complete Unknown to get a bit lost in the world he helped create.Whether the movie also had to lose its way remains another question. —Keith Phipps

A Complete Unknown freewheels into theaters on Christmas.

Babygirl

Dir. Halina Reijn

114 min.

It should go without saying that Romy (Nicole Kidman), the CEO of a company specializing in warehouse automation, had to jump through more than a few hoops to achieve her position. Yet midway through the movie Babygirl she doesn’t just say it, she details each and every hoop, a gauntlet of tasks and interrogations with a difficulty level to rival Kirk’s Kobayashi Maru ordeal that includes calculating the number of ping-pong balls that could fit in a particular room. It also goes without saying that, as a woman, she’s had to work harder than most to hold onto that position. Babygirl, the third feature directed by Halina Reijn (Instinct, Bodies Bodies Bodies), says this for her, depicting a workplace in which even the smallest slip-up could threaten her career, no matter how much power she’s accumulated. Romy has to be perfect and she pretty much is, both at work and at home, where she enjoys a warm relationship with her theater director husband Jacob (Antonio Banderas) and their two daughters Isabel (Esther McGregor) and Nora (Vaughan Reilly).

Romy has it all but it’s all precariously balanced and requires her to maintain absolute control at all times. And, on some fundamental level, Romy doesn’t want that. When Samuel (Harris Dickinson) a frank new intern, begins making suggestive comments to her she responds, not so much because he’s attractive, though he is, as the nature of those comments, which suggest he knows what she wants and she wants to be bossed around. When the two begin an affair, it’s a kind of double power imbalance. Romy surrenders her will to Samuel behind closed doors while remaining the boss in the office. But a word from Samuel could change all that. Who’s in control can be a matter of perspective at times.

Babygirl has to perform its own balancing act. Reijn, who also scripts the film, invests every moment with an uneasy ambiguity. In one scene, Romy agrees to meet Samuel in a hotel room, then tells him that their affair, which had progressed no further than kissing by that point, can not happen. But is she genuinely conflicted and trying to refuse him or is it all part of the act? The way she chides him for bringing her to such a sleazy place has a bit of theatricality to it. She could just be nervous. Or maybe her play-acting extends beyond that room to all aspects of her life.

Reijn’s direction gives the film a voyeuristic charge, observing Romy from a distance, using zooms to create a queasy intimacy, and bringing a cool remove to shocking moments, as when Romy stuffs one of Samuel’s discarded neckties into her mouth. For its first hour, Babygirl plays like an erotic thriller with no clear villain, just the ever-present threat that Romy will be consumed by a mad desire. It’s gripping, perfectly calibrated and determinedly unsubtle—Samuel is introduced subduing an angry dog by coaxing it to obey his will—the sort of filmmaking that demands viewers remain on the edge of their seats even if they’re watching in a multiplex with reclining chairs.

The film’s second half feels less assured, but that mostly feels like a case of the form matching the content. Babygirl starts to feel a bit aimless just as Romy begins to be overwhelmed by confusion and a sense that she’s put herself in a position with no way out, just a way down. It leads to an ending that seems a bit too neat, but it’s the only part of Babygirl that feels that way. Powered by Kidman’s extraordinary performance as a woman in search of a satisfaction she can’t quite define—only for it to find her instead—it’s a provocative film both for the questions it raises about sex, control, and identity and the answers its characters find, while struggling not to lose themselves in the process. —Keith Phipps

Babygirl arrives in theaters on Christmas.

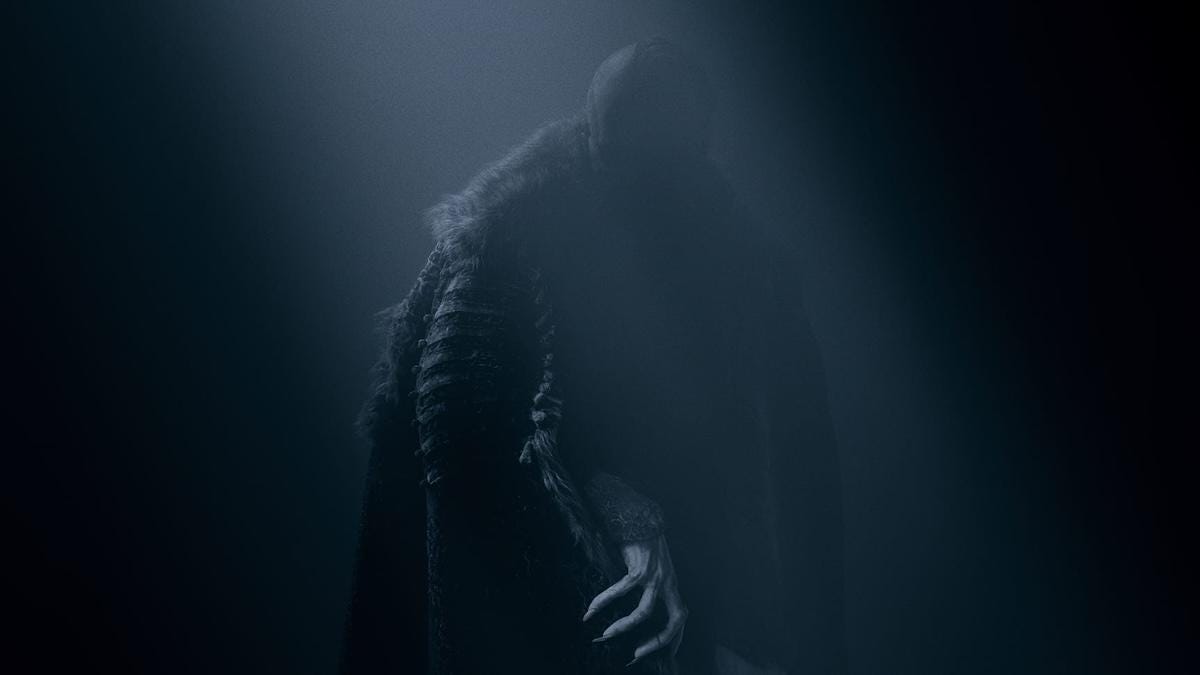

Nosferatu

Dir. Robert Eggers

132 min.

If you skipped past The Lighthouse and The Northman, you might think Robert Eggers’ fourth feature picked up where his debut left off. A remake of F.W. Murnau’s 1922 horror landmark—itself an unofficial adaptation of Dracula—Nosferatu opens with a woman pledging her soul to darkness at the urging of a being of unspeakable evil. And, like The Witch, Nosferatu doesn’t make it easy to know how to feel about that moment, either as the film begins or when the story comes full circle. The Witch made evil look, well, pretty good. (Who doth not like the taste of butter, particularly when the alternative seems so unappealing?) Nosferatu, like its own heroine, has an even more complicated relationship with the dark side, which fills her with fear but also makes her writhe in what looks a lot like pleasure. Sure, evil’s triumph might mean the coming of a devastating plague and a dead child or two, but in a world where goodness is defined by a bunch of dull men who think they know best, maybe that’s just the price you have to pay.

As with each of Eggers’ films, Nosferatu often feels like an act of time travel. Just as The Northman played like the sort of movie Vikings would go see if they had multiplexes, Nosferatu confines itself to a vision of the world appropriate to its setting, a mid-19th century Europe that’s turned the corner toward modernity without letting go of the superstitions of the past (which might not be mere superstition after all). It’s in this world that the newlywed Ellen Hutter (Lily-Rose Depp) feels she’s escaped the darkness of her past—or, in medical terms, her bouts of melancholia and hysteria—as she settles in with her husband Thomas (Nicholas Hoult). But Thomas quickly finds himself forced to leave her for the far reaches of Transylvania, where he’s been sent to complete the paperwork on a real estate transaction. It seems the aged Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) would like a change of scenery and plans to move to, of all places, the Hutters’ hometown of Wisborg, a pleasant little city that straddles a canal.

While staying close to the narrative and spirit of Murnau’s film—with an overheated sexuality on loan from Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula—Eggers layers on the creeping dread and mounting intensity that have defined his films since The Witch. The lead-up to Thomas’s arrival at Orlok’s castle, which includes a stop at a fearful village whose residents essentially tell him he’s doomed (even before he witnesses a strange midnight ritual), feels like it’s setting an impossible bar for the creepiness that awaits him there. But the scenes that follow deliver, pairing a pervasive sense of decay with Skarsgård’s menace to create a claustrophobic nightmare. (Skarsgård’s Orlok looks a bit more human, but no less disturbing, than the Orloks of previous Nosferatus). Yet those scenes, disturbing as they are, look like a mere prelude to Orlok’s journey to Wisborg, accompanied by a plague that brings both death and civil disorder.

Any lightness, such as it is, comes from Willem Dafoe, who delivers a wonderfully eccentric performance as Prof. Albin Eberhart Von Franz, a brilliant scientist whose insistence on pursuing his study of alchemy and the occult has made him an outcast. Yet Dafoe never winks as the world around him begins to prove him right and he works with Ellen to devise a plan to end Nosferatu’s reign of terror, no matter what the cost. What follows, while staying true to the original, underscores the moral murkiness at the heart of Nosferatu in ways that put it in conversation with some of Lars von Trier’s most famous films. Eggers’ respectful, scary remake finds new ways to disturb while teasing out the most unsettling elements of the original’s subtext. It’s a visceral experience in the moment and one sure to trouble dreams after that moment has passed. —Keith Phipps

Nosferatu floats into theaters on the holy day of Christmas.

Publishing note: We’ll be taking tomorrow off but will be back on December 26th with reviews of The Fire Inside and Better Man. Then next week we’ll offer our picks for the best movies of the year.

Nicholas Hoult for the James Brown "Hardest Working Man in Showbiz" award. Holy cow, he's the male counterpart to Anya Taylor-Joy for this year for sure...

And Keith for the same for writing all three reviews! Merry Christmas to you and Scott and the fellow Revealers. All three of these movies look like they are worth watching, so looks like we filmgoers got our presents early.

Now that people have had a chance to see both I can float my crackpot theory that NOSFERATU and BABYGIRL tell sort of, kind of the same story.