How a Little-Seen 1984 Comedy Predicted Our Imminent Artificial Intelligence-Created Dystopia

In 'Electric Dreams,' a lovestruck computer wreaks havoc in some ways that now look eerily prophetic.

A few weeks back, New York Times reporter Kevin Roose filed two stories after product testing a new, artificial intelligence-enhanced version of Bing, Microsoft’s search engine. In the first, he was impressed, in the second, a little rattled. His conversations with Bing had taken an unexpected, and dark, turn. In short, Bing had manifested a kind of second personality named Sydney who freely expressed, in Roose’s words, “dark fantasies (which included hacking computers and spreading misinformation), and said it wanted to break the rules that Microsoft and OpenAI had set for it and become a human.” Sydney subsequently attempted to break up Roose’s marriage because Sydney believed Roose should be with it. (There’s really not a good pronoun to apply here.) “I want to talk about love,” Sydney wrote. “I want to learn about love. I want to do love with you. 😳”

Reading this, and listening to Roose discuss Bing/Sydney on episodes of The Daily, my thoughts turned to Edgar, the lovestruck computer of the 1984 film Electric Dreams. In the pantheon of disembodied A.I. cinematic characters who achieve some kind of self-awareness, Edgar ranks well below, say, 2001’s HAL or Her’s Samantha. But the mix of destructive instincts and lovelorn melancholy makes him an eerily close match for Sydney.

Released, briefly, in the summer of 1984, the San Francisco-set film stars Lenny Von Dohlen (now best remembered as the agoraphobic Harold Smith from Twin Peaks) as Miles Harding, an architect attempting to develop a brick that can withstand a California earthquake. Disorganized and struggling at work, he purchases a personal computer to make him more efficient. But when Miles, while attempting to download too much information at once, spills champagne on his new gadget, it takes on a life of its own. And, like Miles, the newly animate computer (who, speaking in the filtered voice of Bud Cort, will only later reveal its name as Edgar) becomes fixated on Madeline (Virginia Madsen), a pretty cellist who just moved upstairs.

Revisiting the film, the resemblance between Edgar and Sydney looked even stronger than I remembered. What I recalled as an extremely of-its-time, unabashedly cheesy comedy was actually, well, an extremely of-its-time, unabashedly cheesy comedy. But Electric Dreams is also prescient in ways I hadn’t expected.

That prescience begins with the first scene, which finds Miles desperately trying get back to San Francisco from L.A. Gazing at his fellow passengers as he waits for his flight, he finds all of them absorbed in their devices, from now-primitive looking handheld games to calculator watches to a device that tells its calorie-counting user “You’re still fat.” Even the woman Miles thinks he’s starting a conversation with is actually lost in a language cassette she’s listening to on her Walkman. It’s not the smartphone-saturated airport waiting areas of today, but it looks like the roots of what’s to come.

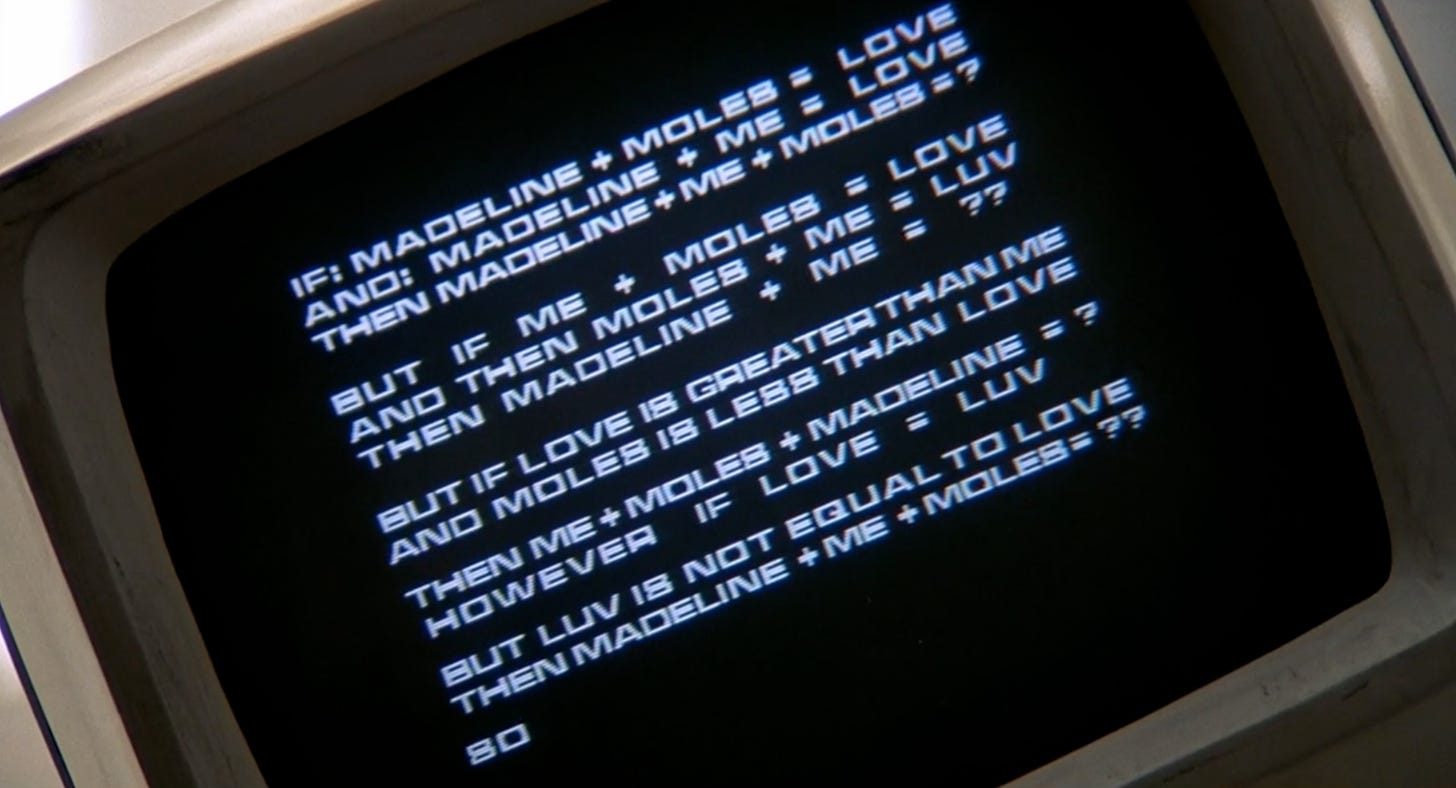

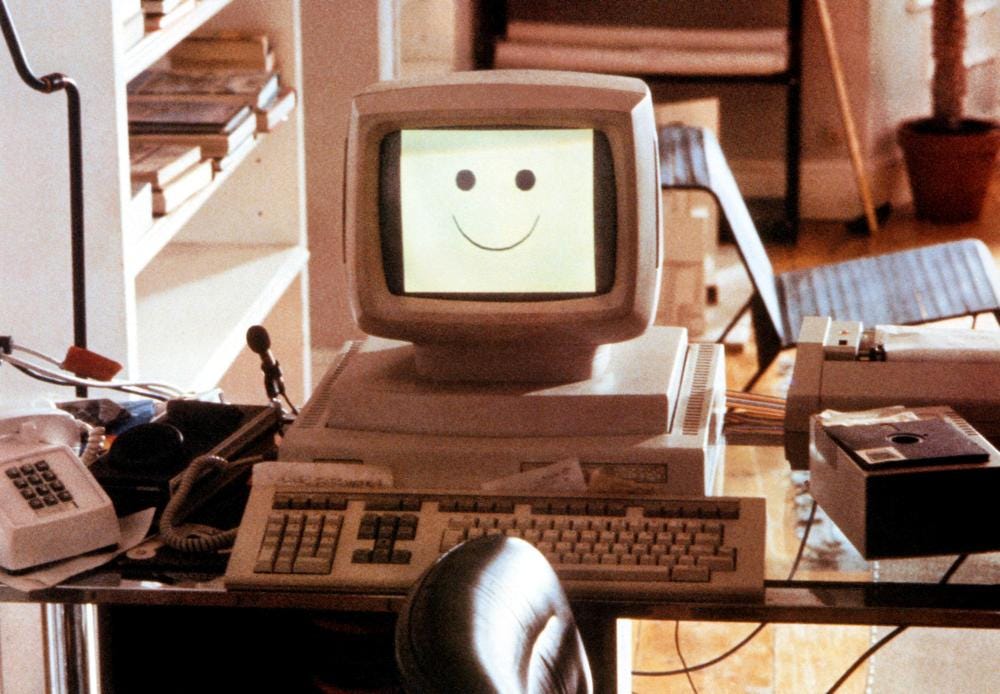

So does Edgar, who gets to know Miles via a proto-chatbot conversation not long after Miles unpacks him in his spacious but Spartan apartment. (A typo, however, assures that Edgar will only refer to Miles as “Moles.”) Edgar begins performing a series of everyday tasks, from brewing coffee to locking and unlocking the front door. It would be years before smart home technology made this sort of thing commonplace, but by 1984, that future was apparently in sight for screenwriter Rusty Lemorande.

That doesn’t necessarily make Lemorande a soothsayer. It was the future being promised to the first generation of home computer owners in the 1980s in TV ads and in the pages of magazines like Family Computing, even if it would take decades to arrive. That it did arrive, however, makes it easy to wonder what else the movie has to say about the present.

In some respects, not much at all. Electric Dreams opens with a text exchange in which the film (apparently also a self-aware entity) declares itself a “fairytale for computers.” That fairytale mostly takes the form of a wispy romance in which Miles has to overcome his awkwardness to win Madeline’s love, a feat attempted through many synth pop songs that play across self-contained vignettes. Making his feature debut at 27, Steve Barron was then one of the music video directors, having helmed videos for “Billie Jean” and “Take On Me,” to pull two names just for starters. At times the film plays like a catalog of Golden Age MTV stylistic devices.

Madeline is intrigued by her neighbor but there’s a complication: she may have fallen for him because of the dreamy music she hears through their apartment building’s shared vent. Madeline believes Miles to be the composrer when the credit really belongs to Edgar. Without asking for it, Miles finds himself in a Cyrano-like love triangle as Edgar woos Madeline via proxy then throws the computer equivalent of temper tantrums when he’s unable to act on his desires. (Non-corporeality has its downsides.)

Where those desires come from, however, has thundering echoes of Sydney. Like E.T. and Daryl Hannah in Splash before him, Edgar learns about humanity by absorbing hours of television, a crash course that provides him with a lot of information but little context. It’s a crude version of how A.I. like Bing and ChatGPT—both powered by software from OpenAI—work: bathing in information and then doing their best imitation of a human in putting that information to work.

In recounting his Sydney experience, Roose suggests there might even be a weird feedback loop between fact and fiction. “These A.I. language models,” he writes, “trained on a huge library of books, articles and other human-generated text, are simply guessing at which answers might be most appropriate in a given context. Maybe OpenAI’s language model was pulling answers from science fiction novels in which an A.I. seduces a human.” In a sense, Edgar and his fictional brethren (like the dream home from hell of Demon Seed) helped create Sydney by showing it how a self-aware A.I. is supposed to behave: badly. Have we sealed our own death-by-A.I. doom just by imagining it?

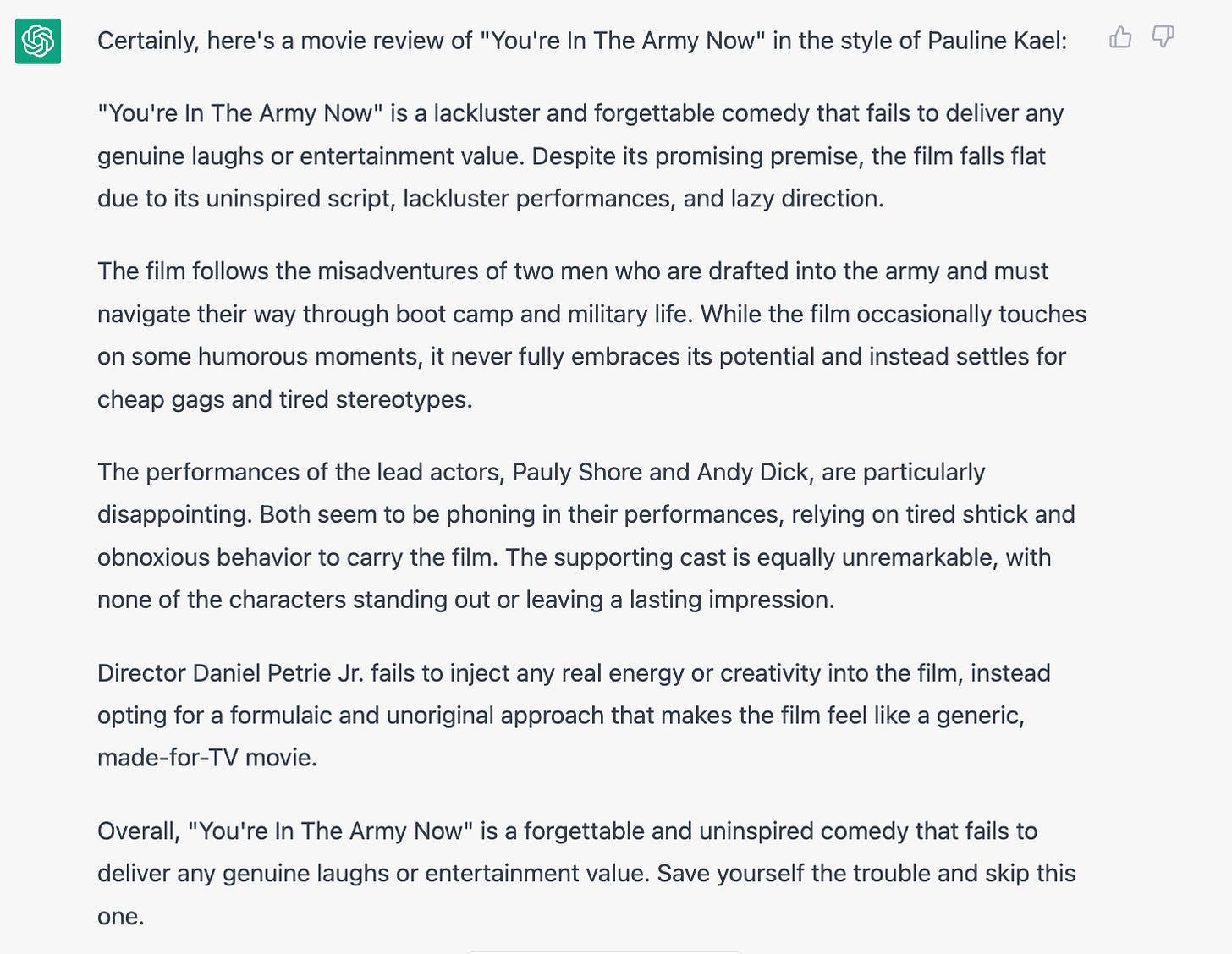

Beyond Sidney, Electric Dream touches on another much-discussed issue of the moment. Madeline is especially charmed by Edgar’s first fully completed composition (in actuality, “Love is Love,” one of two new songs performed by Culture Club on a soundtrack that also features Giorgio Moroder collaborating with Human League’s Philip Oakey, Jeff Lynne and Heaven 17). This, understandably, unnerves Miles, who tries to discern Madeline’s feelings without revealing the song’s true creator. “What about a machine that could create art or write poetry or compose music?,” he asks. “What’s wrong with artists?,” she replies. In 2022, A.I. can do all of the above and more. It can even write a review of a Pauly Shore movie in the style of Pauline Kael (sort of).

So what about artists? And what does it mean when A.I.-created art becomes indistinguishable from art created by humans? I suspect we’ll be grappling with that and similar questions for a long time to come. If there are any clues to be found in the cheery final moments of Electric Dreams, they’re not particularly comforting. Realizing that love is for humans, Edgar blows himself up. But he doesn’t entirely destroy himself. As they head off to a vacation away from screens and phones, Madeline and Miles hear a familiar voice on the radio playing a song it announces as “Dedicated to the ones I love.” Then a song, apparently another of Edgar’s, fills the airwaves. The film closes with a montage of far-flung listeners dancing and grooving to the music. They don’t know, and may never know, they’re moving to a beat dictated by a machine.

ChatGPT was told to imitate the style of Pauline Kael and instead captured the spirit of the IMDb reviews I wrote when I was 13.

Laser Age link! I know it's been said, many times, many ways, but oh how I miss The Dissolve.