Four Looks at Buster Keaton: A Conversation With 'Camera Man' Author Dana Stevens

'Slate' film critic Dana Stevens walks us through four memorable moments in the film pioneer's career

It’s easy to learn a few facts about Buster Keaton and think you know the whole story. Born in 1895, Keaton became a vaudeville star as a child as part of the family vaudeville act the Three Keatons. He transitioned from stage to screen just in time to become one of the great comic actors of the silent era, combining a stone-faced expression with an unusual gift for crafting elaborate (and often dangerous) comedic set pieces. From 1920 to 1928, he found great success as an independent filmmaker, then signed with MGM, a deal that coincided with the coming of sound. The popular conception is that for Keaton ahead lay disappointment and drink, but as we’ll see below, it wasn’t that simple.

Slate film critic Dana Stevens’ new book Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century puts Keaton’s life and career in a cultural and historical frame of Cinemascope dimensions. From its early chapters, which set the Three Keatons’ act within the context of the early 20th century child welfare movement, to its detailed look at Keaton’s successful late-life career as a live performer and in-demand TV star, Camera Man challenges simplified readings of Keaton, whether by offering a detailed account of the restaurant in which Keaton contemplated making the move to film — itself a symbol of a 20th century coming into its own — or using Keaton and Chaplin’s one film appearance together to draw a compelling contrast between the two greats’ lives and art. In conversation with The Reveal, Stevens discusses four Keaton appearances from various points in his career.

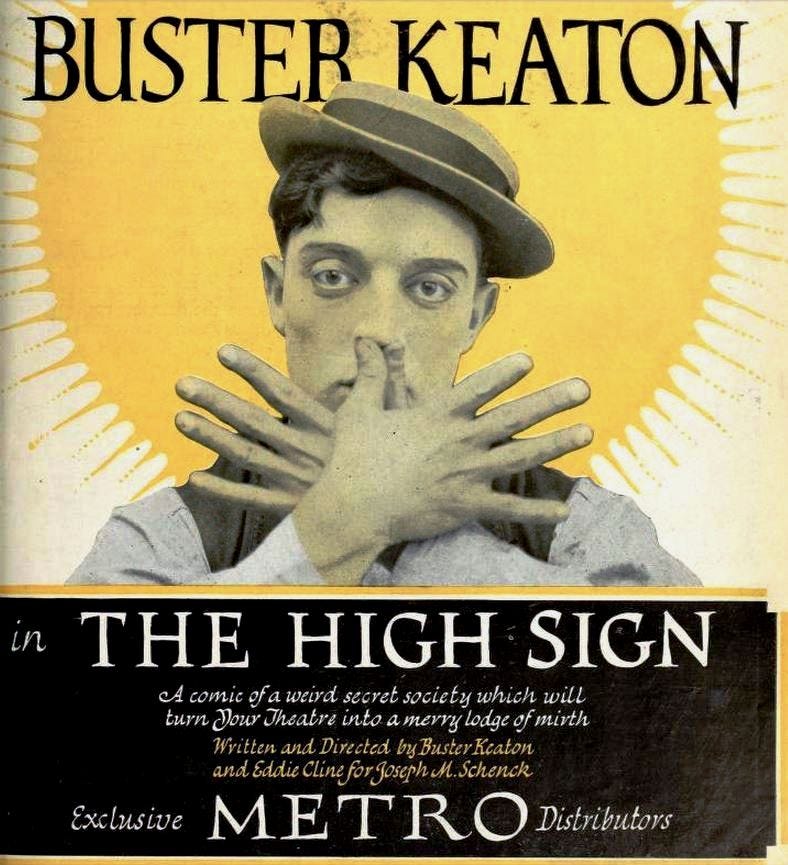

“The High Sign” (1921)

I wanted to start with "The High Sign,” both because it's the first independent film Keaton shot, also because its title doubles as your Twitter handle. Tell me about this film and your relationship to it.

The High Sign was the name of this pseudonymous blog that I wrote in the early 2000s that ended up turning into a career in criticism, although really it just started out as a place to not go crazy, because I had a day job that was boring and I needed some outlet for writing. And why was it called the High Sign? I just thought that was a cool name for a site. It’s a secret signal to someone, like if you're at a party and you and your spouse have a code word or gesture, like, "If you look over at me and I'm, whatever, tugging my earlobe like Carol Burnett, that means I want to leave the party.” That's a high sign.

[My website] took its title from the Keaton short, but it didn't have anything specific to do with him or with silent movies. It was just a contemporary movie-review blog. But it’s just one of the many ways that Keaton was sort of embedded in my life story over the past few decades.

“The High Sign” was the first film Keaton made as an independent filmmaker, but he held it and released other films first. To me it feels of a piece with his other independents. Where do you see this fitting into his filmography?

It's a great asterisk to have on “The High Sign" that it was his first independent film, but it was the one he chose to shelve for a year. He didn't think it was unworthy of being released. He just thought it was unworthy of being his splashy debut as a solo director. And when you see “One Week,” and the utterly realized perfection of that movie, you can see why he would choose to make that his flagship release rather than “The High Sign.”

“The High Sign” is a link between an earlier filmmaking style and the one that he was growing into. It's got that quality that the Arbuckle movies or even Keystone movies often had, where it's a grab bag. It’s a combination of trick photography and visual jokes, like the hat that he hangs on that painted hook on the wall. Which, if you think about it, is a very un-Keaton joke, in terms of later stuff he would do. It's absurdist and surrealist, imagining this impossible thing, hanging something on a painted hook.

It’s not the kind of joke he would make later on, because he liked real physical things in their real physical place. In fact, he was a real stickler about, "No. I want my real body to be moving through real space in real time, and you can see the whole thing.” Once in a while he would cheat with slow motion or something like that, but almost never with visual trickery inside the camera to make you think something was happening that wasn't happening.

That little hook moment reaches back to an earlier era, to the “cinema of attractions” films that I talk about in the book, that early idea that film was a place to impress people and wow them. It wasn't a place to tell stories, but to do neat stuff. “The High Sign” is full of things like that, whether it's the sharp-shooting tricks or the dog and cat trick behind the house. Or even the cutaway house with people moving through it. It's full of fun stuff, but it's less of a through-composed story. Whereas in “One Week,” the story really flows from the characters, from those two people who are married and building a house together. “The High Sign” is more of a crazy jumble, and that's what makes it fun.

The Keaton persona is there, but he's less of a developed character.

And the way he's thrown off the train at the beginning…It's a fantastic beginning to a career, if you think about it. Of course, it's not the beginning of his career as an entertainer. He’s already had seventeen years on the stage at this point and three years with Arbuckle, basically co-directing. So to call “The High Sign” his debut is a bit misleading, but if you think of it as kind of the moment that Keaton qua Keaton, with his own production company under his own name, enters the world, it's great that the very first thing that happens is a train rushing through. The train is the quintessential Keaton image, and the place where he grew up, and he’s getting thrown off a train. Like, "Here you go!"

The Cameraman (1928)

At the other end of Keaton’s creative independence there’s The Cameraman, the first film he made after he'd signed the MGM. That film gives your book the title. So, let's just start with that. Why is the title significant?

It references the title of the film, obviously. But those two words, “camera” and “man,” — separated, unlike they are in the title of the film — are the two threads of the book. The “man” is the biography and the “camera” is the kind of technological history or history of cinema. The fact that [Keaton and film] were born in the same year, 1895, is mentioned in almost every Keaton bio, because it's a nice poetic convergence. But what interested me in this book was spinning out that relationship throughout the life of both. If they were born together, that means they grew up together. And watching them grow up together was what was interesting.

The movie is kind of the end of a phase. This is his first film with MGM and, to my understanding, the only one on which he enjoyed full creative control.

I would say that both The Cameraman and its followup, Spite Marriage, are holdouts of him managing to still get across something like a Keaton film, but in the format of making a movie at a studio with teams of writers, et cetera. And between The Cameraman and Spite Marriage, his last two silents and his only silents for MGM, it's The Cameraman that most feels like a Keaton movie. Spite Marriage is still good, and it has some great physical comedy in it, but The Cameraman feels like something Keaton might have conceived and come up with at his own studio. I think there's a little more plotting in it than he would've wanted, but it feels like a simple story he might have wanted to tell.

It's his last great film, which also gives it this real sadness. This is the film, that Imogen Sara Smith—she wrote Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy, a great book on Keaton—calls “the last rose of summer.” I love that phrase for this movie, because there's the sense that... I mean, he was still so young. It wasn't even 1930, so he was not yet 35, and this is Keaton’s last expression of a vision that isn't in some way encroached on by the studio and, very soon so completely encroached on that he loses creative control entirely.

Is it accurate to say there's like a little bit more sentiment creeping in than you usually associate with Keaton?

Yeah. And as I say in the book, in Spite Marriage, there are some moments where that feels off, like there's this stuffed dog moment that I write about. And even if you haven't seen Spite Marriage, you can picture it: Keaton using a stuffed dog to sort of flirt with a woman, it’s just way more cute than anything he would do with props in his own comedy.

I don't think The Cameraman has any moments like that, where it clangs and feels, like, not Keatonesque. There are certainly things—like the closeup of his eyes when he's in the MGM newsreel office and he's flirting with Marceline Day, the girl he likes there. It's a beautiful closeup of his eyes above the top of the movie camera, kind of making moony eyes at her. That [closeup] is something he never would've done, I don't think.

But it all works in The Cameraman. Some of the moments that do feel the most him are moments that were not in the script. And part of what makes me feel a presence of something besides Keaton is that it was a scripted movie. Most of his movies weren't. His silents that he made with his own company ... certainly they were planned out meticulously, but there wasn't really a script to follow. The idea was, "Well, we have this mobile dedicated crew that just wanders around L.A., and we'll find a block, and we'll figure out some comedy about it. And then we'll do that." That didn't work with MGM.

In The Cameraman, the Yankee Stadium segment where he plays the ballgame by himself, one of the most beautiful and memorable parts of the movie, was totally improvised. That happened because they went to film on location in New York, which was not that common of a thing to do at the time for an MGM movie, because MGM had their own New York backlot set, which [The Cameraman] ended up using, for example, in the Chinatown scenes.

The great dressing room scene with Ed Brophy, where they're climbing all over each other, that was also totally improvised, so improvised that they had no one to play that part, and they had to get Brophy, who was on the crew. But he was the right size and had the right physicality, so they had him do that scene and that actually launched him on an acting career of his own. Keaton was still trying to get that sort of thing in around the edges, and for his very first movie at MGM, he managed.

That's one of the tragic things about this movie. It was really good. It was a success. Everyone loved it. And yet Keaton wasn't able to leverage it to getting more freedom. He tried to go to [storied MGM producer] Irving Thalberg and say, "Well, look. I can do it. Give me some resources and my own unit, and I can continue to..." I think he says it in almost this many words: "I can continue to make pictures as good or better than The Cameraman." And he never got that, because it wasn't the way MGM worked. So you see this alternate history of Keaton at MGM where, if he could have been trusted to continue to do things right after The Cameraman, he might have made a string of great comedies there and not gone down the spiral that he did.

The Cameraman and the MGM deal coincide with the coming of sound. Can you also imagine an alternate history in which he would’ve continued working in the sound era as well if he’d been given more freedom?

The saddest thing about those horrible early talkies at MGM — a string of eight, ten movies that he made in the early talkie years that were terrible — is they were all successes. They were financial successes, both because MGM had a really strong marketing arm, and because Keaton was popular and his name on a marquee would sell tickets.

It's easy to think he made all these great movies and was such a success and ah, then the poor guy was a drunk making flops, but he wasn't. He was a drunk making successful bad movies, which must have been really painful for him. They were popular movies. Obviously, he was a rich movie star in the '20s, but [his silents] didn’t rake in as much money as most of the MGM talkies did.

I can visualize a different early career for him in sound. He didn’t have a voice that didn't suit his physicality. And certainly on the stage he had a history of talking and singing and dancing. He was sort of a utility player in vaudeville who could do anything, in addition to slapstick. So it really is a shame that nobody at MGM knew how to use him or trusted him to be his own creative chief.

This Is Your Life (1957)

Your book includes a passage about Keaton’s appearance on This Is Your Life, the sadistic '50s show in which guests were unsuspectingly forced to relive their past. I'd seen an episode or two years ago, but I’d forgotten just how painful this experience must be. And for Keaton, it seemed particularly painful. He’s kind of presented as, “Do you remember this object of the past?”

Keaton and his wife Eleanor did it because they were trying to promote this terrible biopic that he sold the rights to his life for 1957’s The Buster Keaton Story, starring Donald O’Connor. It's obvious that the Keatons are uncomfortable in that format, and that he doesn’t like having his life narrated in that way—especially, I’m sure, in service of a biopic that he was not thrilled to have out there. The Keatons were glad it was a flop and quickly sank out of sight. It allowed them to buy the house where they spent their last very happy decade together.

Watching that appearance is a mixed thing. It’s painful to see him being put through memories from the past, but it's also a rare moment for Keaton fans to see an unguarded part of him--really unguarded, because he was ambushed by the producers when he thought he was going to a meeting. You see his offscreen self, which is very shy. Even though he obviously loved performing, he did not love being on camera as himself.

My favorite moment is when Louise Dresser hugs him and says, “Don’t cry or I’ll cry too,” and wipes the tears out of his eyes. Dresser was the [singer and actress] who was his sister's namesake, and his parents considered her a kind of vaudeville companion and compatriot. And the idea of her showing up and just hugging him like a little boy and making him cry, it's very sweet. But you do really want that show to end so he can go home and be off the air and be comfortable.

The Twilight Zone: “Once Upon a Time” (1961)

Your book changed my perception of Keaton’s later years. I didn’t know much about him finding stability and success later in his life. I knew he turned up in Beach Party movies, but it seems by then he was kind of a celebrity again, someone people would know from television, including this very funny episode of The Twilight Zone. Do you know how that came about?

I’m not sure exactly how it came about in terms of who contacted him or how Rod Serling got interested, but it would’ve been a natural fit, because he is a huge figure on TV at that point. He’s kind of ubiquitous as a guest star, somebody who’s on variety shows like Ed Sullivan and who does guest spots on sitcoms and Candid Camera. Anywhere there was this sort of a vaudevillian space in TV, he was in it.

Vaudeville and TV overlapped a lot in those early years because that was the feeder, in a way. Vaudeville was dying, or had already died by that point, but there were all these stars who had come up from it who could do variety-type acts, and very early TV, especially, was all about variety, hence the term “vaudeo.”

Keaton did his first TV appearance in 1949 and would’ve naturally been somebody to go to for a Twilight Zone episode. And Richard Matheson really writes to Keaton’s strengths. [The episode] is about time travel, and the depiction of time is something that really struck me about several of his TV appearances, including The Silent Partner, which was this made-for-TV drama where he plays a washed-up silent star who sees his old director, played by Joe E. Brown, also of vaudeville fame, getting an award on TV. And Keaton’s this drunk sitting in a bar watching it happen.

All of these shows were meta-stories that were trying to retell Keaton's story, and not quite getting it right, because he wasn’t, at that point, a broken-down drunk witnessing somebody else's success in a bar. On the contrary, he was getting more calls than he could answer for various jobs, including the Beach Blanket Bingo things, which were not taken out of desperation but because he never turned down work. They paid well and they were a day's work, and he was socking away money for his much younger wife, who he knew would outlive him.

His Twilight Zone is almost like a Wizard of Oz story about him coming into the 1960s from the late 1890s. He explores the future and then at the end, with his crazy time travel helmet, he decides, “No, I’m going to go back to my time.” Once again, it’s a sweet story, but it really doesn't capture the spirit of Keaton, who did want to stay in the future, always wanted to be moving into the future, and was not a nostalgia act. I’m sure he was very happy his movies were being rediscovered and restored by the time he died. But he was not a nostalgic character who wanted to look back and relive the past.

I love the image from your book of him watching television and then barking directions at it, how things could have been done better.

In addition to being a director and stuntman and editor and obviously a performer, a part of him was a critic as well. There are a few descriptions of him watching TV. There's that one where he's yelling, “Cut!” at the camera, as if he were directing it. But there's others where he's re-casting things in his mind or saying, “This isn’t how it should be done.” If you think about the amount of comedy he had witnessed in his life, whether making it or watching it on stage, growing up as a vaudevillian, I’m sure he considered himself somebody whose taste in the area of comedy was worth paying attention to. And he’s somebody whose taste, in the most crucial years of his career, was totally ignored. That gives those scenes of him watching television an extra melancholy. He was watching it with the eye of somebody who wished that he could have done things differently.

Camera Man is available now wherever books are sold.

I am working through Keaton’s filmography right now in order to properly enjoy Dana’s book. I’d previously only seen The General and Sherlock Jr. (the latter being one of my favorite films EVER) but went ahead and bought all of the Cohen film collections of his stuff as well as Kino Lorber’s release of Three Ages, Our Hospitality and his shorts.

I still have a lot to get through, (mostly all of his shorts) but my biggest takeaway so far is that Battling Butler is one of the most underrated, forgotten classics that ever was. Apparently it was Keaton’s favorite of his own stuff and while I don’t completely agree, I wouldn’t argue against it too much!