Dreams of Arrakis: The quixotic allure of Frank Herbert's 'Dune'

As a new half-adaptation opens this week, there are lessons to be learned from two previous attempts by major directors — one a bomb, one never produced.

Arrakis is the most godforsaken shithole planet in the known universe. Its surface may be beautiful from above—endless desert sands of different textures and subtle changes of color, with scattered outcroppings of rock—but actually living there is close to impossible for outsiders and such an immense pain in the ass for even the native Fremen that their asceticism has developed into a kind of religion. It never rains on Arrakis, so the Fremen have designed the “stillsuit,” a form-fitting outfit that preserves and recycles the body’s moisture, filtering sweat and urine into the drinkable water that accumulates in “catchpockets.” There are stretches during the day when no one can step outside, and even when they can, the faintest movement might draw the attention of the giant sandworms that patrol the surface.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

But the planet Arrakis has the spice melange, a cinnamon-scented psychotropic marvel that is the galaxy’s most coveted resource. Mining “the spice” is a prerogative for Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV, who relies on it to maintain power, and the rivalry at the center of Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune, between the noble House Atreides and the diabolical House Harkonnen, pivots around stewardship of this industrial operation. Those rich pockets of melange are extracted by giant spice harvesters, but because of the sandworms, they can’t stay in one place like an oil derrick. If “wormsign” is spotted in the area, flying machines called “carryalls” swoop down to collect the harvesters and the workers within them, just before a worm can strike. Sounds like the makings of a dazzling cinematic action sequence, right?

Indeed it does, which is why Warner Brothers has opened its coffers for a new adaptation of the book, and why two other major filmmakers took a crack at it previously—one producing a flop, the other never making it past pre-production. The properties of the spice itself hint at why Dune has been so vexing for anyone who tries to adapt it, for two very different reasons:

1. The spice, in large quantities, makes interstellar space travel possible, safely guiding ships through folds in the space-time continuum without moving, at a rate much faster than the speed of light. It is the fuel that powers the immense gas-guzzlers of the years 10,191.

2. The spice is a drug. It extends life and expands consciousness. It has a hallucinogenic effect, heightening awareness and sensitivity and, for some, bestowing on a certain amount of prescience. Just as ships can travel without moving on melange, so can humans. It’s also highly addicting.

Put simply, the spice is analogous to oil and LSD. So in order to make a proper film adaptation of Dune, the story of a Chosen One type who ascends to a Messiah-like power on Arrakis, a director has to be some combination of George Lucas and Alejandro Jodorowsky. No such director exists. That such an author existed to write Dune is the reason it’s such a singular achievement: Herbert carries you along on a hero’s adventure as classically satisfying as a Joseph Campbell monomyth while also expanding into global politics, religion, and war, plus the transcendent qualities of tripping the fuck out.

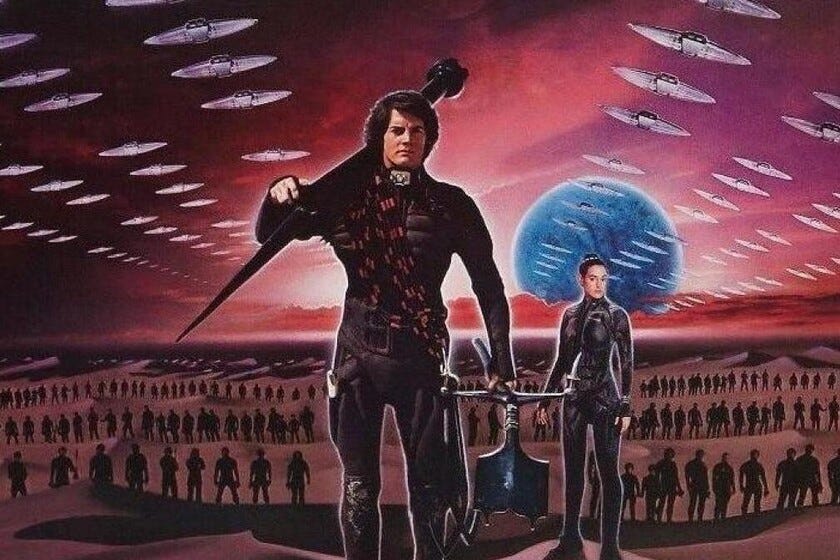

Before Denis Villeneuve’s new adaptation of Dune—review for that coming Thursday—two other directors dreamed of Arrakis, though only one of those dreams came to fruition and surely not as hoped. In the mid-‘70s, French producers secured the rights to Herbert’s novel for Jodorowsky, the eccentric Mexican visionary whose previous films, particularly 1970’s El Topo and 1974’s The Holy Mountain, had become instant cult classics. The failure of that effort is chronicled in the 2013 documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune. (More on that later.) The rights were later snapped up by the Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis, who hired David Lynch, the director of Eraserhead and The Elephant Man, for the job. It didn’t work out, either. Sometimes the dream factory is more factory than dream.

“Once you know your Fremen from your Bene Gesserit, you’ll be ready for the adventure of a lifetime.” — MCA Home Video handout for David Lunch’s Dune

And yet Lynch was an inspired choice, maybe the only person who could conceivably pull it off. The Elephant Man had proven that the experimental techniques he had developed on Eraserhead—the external manifestation of internal terror, the complex and unsettling sound design, the spare black-and-white imagery—could be folded into a story of larger mainstream appeal. More importantly, there are elements of Herbert’s novel that appeal strongly to what we’d come to understand as Lynch obsessions: Dreams and nightmares that reflect characters’ anxieties and hint at things to come, and innocence lost to the encroachment of unfathomable evil. Under the right circumstances, without the strictures of time and budget, it’s still possible to imagine a great version of Lynch’s Dune, one that finds some compatibility between his sensibility and Herbert’s epic mind-trip.

The biggest obstacle to anyone trying to crack Dune is practical: How do you lead audiences through the dense galactic intrigue over the spice and the various houses and parties angling for control of Arrakis? And how to make clear the difference between the Fremen and the Bene Gesserit, or the Sardaukar and the Harkonnen, not to mention dozens of made-up terms for objects like stillsuits, thumpers, or a gom jabbar? Paperback editions of Dune come with a handy glossary, but passing leaflets out in theaters before a movie—this happened later with Peter Greenaway’s impenetrable Prospero’s Books—is more or less waving the white flag. As well as Lynch does in trying to fold narrative information in the opening monologue by the disembodied face of Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen), the Emperor’s daughter, or through “filmbooks” that describe the basic details of life on Arrakis, those unfamiliar with the novel are doomed to be lost.

The scenes that open Dune, however, suggest that maybe Lynch has cracked the code—or, at a minimum, he has a distinct command over the look and feel of Herbert’s world that may make up for hiccups in plotting. His Dune seems to exist in the same universe as The Man in the Planet in Eraserhead, a howling void where the fates are manipulated by obscure levers, like “the man behind the curtain” in one Lynch’s go-to reference points, The Wizard of Oz. And as the day-to-day miseries of his hero in Eraserhead are compounded by the industrial clang of the city, Lynch emphasizes the heavy, hissing machinery that powers civilization in the known universe.

When the Emperor (José Ferrer) takes a meeting with a mutant Guild Navigator, ordering him to kill a young man of destiny from House Atreides, the creature gets rolled in on what looks like a giant locomotive car—not the fleet vehicle one might imagine can zip gracefully through the space-time continuum. Our introduction to Giedi Prime, the factory-like planet of House Harkonnen, is painted in similarly grotesque terms, with the Baron Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan) receiving constant treatment for the leaking sores that cover his face, as if his corruption and venality was too much for his body to suppress. In a fiendish Lynch invention, the Baron’s prisoners and slaves have “heart plugs” installed in their chests like sink stoppers, and easily yanked at his sadistic (and predatorily homoerotic) whims.

In the first of their many collaborations, Lynch cast Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides, a Chosen One navigator through the world of Dune but less a conventional hero than a combination of the uncertain and the uncanny—he’s a dreamer who’s having to come to terms with his special place in the galaxy. MacLachlan’s innocence and curiosity would come through more forcefully two years later in Lynch’s Blue Velvet, partly because here Lynch has too busy a narrative agenda to dwell on it for long: Paul’s the son of Duke Leto (Jürgen Prochnow) and Lady Jessica (Francesca Annis), a member of the Bene Gesserit sisterhood, and a naif whom Bene Gesserit prophecy suggests may be the fabled Kwisatz Haderach. Once House Atriedes sets up shop on Arrakis, falling into a trap laid by the Emperor and Baron Harkonnen, Paul is swept into a war that sends him into the world of the Fremen, the natives of the planet, who occupy seeming uninhabitable space, living in underground pockets called “sietches.”

There is a point, regrettably early in Dune, when you can feel the immense narrative engine of Herbert’s novel getting the better of Lynch, who seems to have blown through his allotment of time for vivid scene-setting and character work in the opening reel. Where Lynch could work homespun magic on a shoestring in Eraserhead, he’s undercut badly by the shoddiness of Raffaella De Laurentiis’ production, which could not scale up from the sword-and-sandal fantasies of Conan the Barbarian and Conan the Destroyer, the two films she had produced previously. At 137 minutes, Dune is a drastic abridgment of Herbert’s novel that has the effect of seeming much longer than it is, as the rush of action and mythology becomes increasingly dark, soupy, and under-financed.

It’s also plain that Lynch doesn’t care much for the political undergirding of Herbert’s book, with its references to the Middle East, the exploitative forces of Western imperialists, and the jihadist uprising of the Fremen, who by description resemble the nomadic, desert-dwelling Bedouins. His Fremen are all white—notably Linda Hunt as the housekeeper Shadout Makes and Sean Young as Paul’s love interest Chani, who is played in the new film by Zendaya—and any allusions to real-world conflict are scrubbed out. Gone along with it is perhaps the most important—or least the most distinctive—aspect of Paul’s character, which is that his ascension to a Messiah-like status may not be a righteous path. Paul’s prescient dreams of jihad haunt him because it’s the most likely of the outcomes laid out before him. That’s an essential (and novel) a theme of Herbert’s book, one that connects it to the second half of another desert epic, Lawrence of Arabia, which ends with the hero’s ideals in tatters. Lynch’s Dune doesn’t have time for that kind of ambiguity; it barely has time for Paul’s triumph as it is.

Perhaps the perfect adaptation of Dune is one that isn’t made at all. After spending $2 million in pre-production in the mid-‘70s, Alejandro Jodorowsky and his French producer, Michel Seydoux, came to Hollywood with an extraordinarily talented team and an illustrated, shot-by-shot script that looks like the Mexico City phone book. (Jodorowsky boasts it would have been a 14-hour film, but that number likely didn’t come up in pitch meetings.) Though no one ever says as much in Jodorowsky’s Dune, an admiring 2013 documentary about the making and unmaking of the project, there’s great strategic value in bringing such a fully imagined film to studios, with the comic book artist Jean “Moebius” Giraud sketching every shot and line, along with vividly rendered characters, costumes, backdrops and machines.

The reason they needed that strategic approach: Even in the heart of the 1970s, when the auteur lunatics rans the Hollywood asylum, you’d have to be out of your mind to give Jodorowsky $15 million to make Dune.

The best argument for Jodorowsky is that El Topo and The Holy Mountain had connected with the hip audiences that studios had coveted since Easy Rider slipped past the guardians of popular culture. But $15 million is a lot of money—or rather, the $5 million piece of the budget the producers were seeking at that point—and there’s no evidence in his previous films that he could handle the storytelling demands of Herbert’s book, much less the basic conventions of pacing and managing actors. (Jodorowsky had cast his mad self in the lead roles in his previous two films.) To cast his rejection as another example of Hollywood’s cravenness in the face of originality and genius is close to laughable. His sensibility was on another planet, so far away it would take an ocean of melange to get there.

But we can dream, can’t we? We can dream of music by Pink Floyd, sets and design by Chris Foss and H.R. Giger, special effects by Dan O’Bannon, and a cast that includes David Carradine, Mick Jagger, Udo Kier, Salvador Dali, and Orson Welles. (Foss, Giger, and O’Bannon would team up brilliantly on Ridley Scott’s Alien a few years later.) We can dream of an opening shot that pulls back on the endless expanse of the universe itself, which Jodorowsky envisioned as his homage to A Touch of Evil. We can dream of a truly audacious visionary getting high on the spice, and making the type of phantasmagoric experience that he genuinely believed would change the world—or, at a minimum, deliver a contact high for the ages.

One obstacle to dreaming of a Jodorowsky Dune is the all-male gallery of talking heads assembled for Frank Pavich’s documentary, includes the filmmaker Richard Stanley (Hardware), who was accused of domestic violence, and critic Devin Faraci, who stepped down as editor of Birth.Movies.Death. after being accused of sexual assault. And Jodorowsky himself once stirred controversy by saying that a rape scene in El Topo was unsimulated—he has since called the claim “surrealist publicity”— here likens adapting Herbert like a marriage where you “[rip] open the costume and rape the bride.” Whether or not you give him the benefit of the doubt and ascribe such comments to a passion that gets the better of him, Jodorowsky’s language suggests the immense challenge any studio would face selling his Dune to the mainstream.

Not surprisingly, Jodorowsky gravitated toward the mystical aspects of Dune, with its sense of cosmic predestination and its transformation of Paul Atreides into a spiritual leader. Though the documentary doesn’t dig deeply into Herbert’s novel, Jodorowsky did make one notable tweak to by giving Paul an unusual origin: In this version, Paul’s father, Duke Leto, is castrated, so there’s a sequence where Lady Jessica turns a drop of his blood into semen, which we then follow into her body. (“He’s not a son of sexual pleasure but spiritual pleasure,” says Jodorowsky.) As with Lynch’s Dune, Jodorowsky seemed more interested in Paul becoming the Messiah than any negative consequences that might go along with this transformation. The director seems absolutely sincere when he says he wanted Dune to change the world, and seems to believe that likely wouldn’t happen if Paul’s transcendence wasn’t as pure as his virgin birth.

Even those most pessimistic about the reality of a Jodorowsky Dune—those like me, basically—can confess that it would have been a hell of a thing to watch. He wanted the film to feel like an LSD hallucination without needing to take the drug, and he’d proven that he could conjure images of surrealistic grandeur. Looking at Moebius’ mock-ups for designs like the ornithopter, the bird-like flying machines that zip around Arrakis, or the massive spaceships powered by melange, it’s clear that this Dune had the opportunity to give a colorful, tie-dye makeover to a genre that had long been dominated by an austere, slate-gray palette. You can practically hear that Pink Floyd score—which was to have been recorded not long after its seminal Dark Side of the Moon album—and imagine Dune like one of those far-out laser shows set to their prog-rock grooves. Like Paul Atreides, you’re invited to close your eyes and dream of Arrakis. No existing film can compete with that.

I'm a big fan of Lynch's Dune despite its flaws. To me it feels like he got halfway through the book before he realized he had to wrap everything up in another half hour. I have to wonder what his film might have looked like if he didn't have the real-world budgetary and time constraints (both in terms of production time and runtime). I'd happily watch a 4-hour version of Lynch's Dune if it meant he got to give the second half of the book as much attention as the first.

Which is something that makes me particularly excited for Villeneuve's attempt. He's not pretending to adapt the entire book and just relying on positive reception and goodwill to get to film the rest. I really hope it's good (and it sounds like it is) and that he gets his chance to finish the project.

I like Lynch's Dune, even though I know it is also incomprehensible and flawed in many ways. It has to be one of the weirdest Blockbuster-budgeted movies ever made, and while I agree that the quality of the visuals is wildly inconsistent, when it looks good, it looks REALLY good.

I kind of feel like Jodorowsky's Dune, the documentary, is probably the best case scenario for imagining what the film could be. I can't conceive of that project ever working, and this is one time where the studios were probably 100% right to NOT go that route. Sure, it would be a hell of a thing to see, but I also fully expect that it'd be borderline unwatchable.

Here's hoping the new film finds an audience enough to make the next film.