‘Dreamcatcher’ at 20: What Was That All About, Anyway?

In 2003, a lot of talented people made a baffling Stephen King adaptation. It's not good, but time has been unexpectedly kind to it.

Since it’s impossible to talk about Dreamcatcher without talking about the shit-weasel, we may as well start with it. An adaptation of Stephen King’s 2001 novel of the same name, Dreamcatcher heavily foreshadows its most memorable foe via a rumbling tummy and swelling belly before revealing it in its awful fullness around the 45-minute mark. After making their annual retreat to a remote cabin, four childhood friends take in an unexpected guest in the form of Rick (Eric Keenleyside), a hunter who isn’t feeling too well. After Rick retreats to the bathroom with crippling gastric distress, then stays behind its locked door for an alarming amount of time, two of the friends—Jonesy (Damian Lewis) and Beaver (Jason Lee)—decide to break down the door for a wellness check. Inside they find Rick dead but still seated on the toilet—and somehow still capable of excreting something. What could have merely been some kind of horrifying punctuation mark to a dread illness proves to be a violent creature intent on escaping the toilet in which Jonesy and Beaver have trapped him. There can only be one word name for such a beast: shit-weasel.

The reception that greeted Dreamcatcher when it arrived in theaters in late March 2003 echoes Jonesy and Beaver’s reaction. What was this movie? Do we even have a name for such a thing? It’s a response that the shit-weasel alone can’t explain and a description of its plot can only suggest.

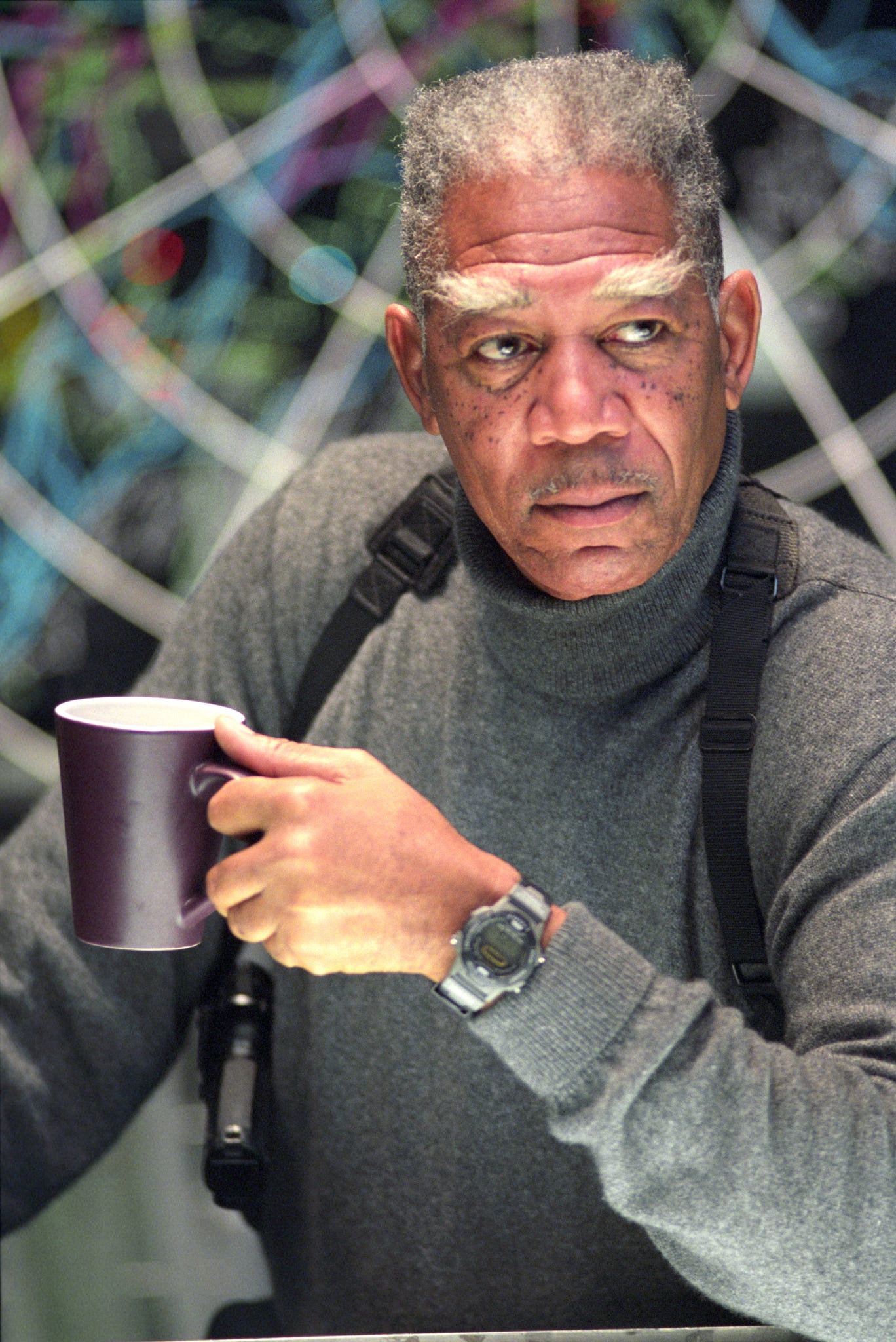

Joining Jonesy and Beaver on their ill-fated getaway are Pete (Timothy Olyphant) and Henry (Thomas Jane). Flashbacks reveal that the four share a psychic bond that developed after they saved an (apparently) intellectually disabled boy named Duddits (played as an adult by Donnie Wahlberg) from a group of bullies. This has been a blessing and a curse and will prove essential when they become the frontline defense against an alien invasion. Some of them, anyway. Some die, and Pete finds himself sharing his body with an alien that speaks in an accent that makes him sound like a mean-spirited cousin to the Geico spokes-gecko. Also on hand: Morgan Freeman as Col. Abraham Curtis, a veteran commander of a covert alien-fighting force who’s been driven mad by the fight and Tom Sizemore as Lt. Owen Underhill, Curtis’ second-in-command, who blanches when his boss suggests they escalate their quarantine protocols into mass slaughter, just to be on the safe side.

I bring Dreamcatcher up again two decades on not just to kick it. Almost any movie can be made to sound ridiculous when reduced to a bare synopsis (though it’s easier with some than others) and critics and audiences so thoroughly rejected the film in 2003 that piling on, even after all these years, seems cruel. But I don’t bring up again to champion it as a misunderstood gem, either. It’s tough to call Dreamcatcher a good movie. But it is a pretty fascinating movie, a mix of curious decisions and studio money of the sort we just don’t see anymore, and in some ways the preceding plot description only scratches the surface. As our own Scott Tobias wrote at the time, “How many other films could recall Scooby-Doo, Apocalypse Now, a disease-of-the-week movie, and Japanese animation within the space of five minutes, and still have plenty of bad ideas to spare?”

That Dreamcatcher isn’t terrible through and through is part of what makes it compelling. In fact, that it’s terrible at all is kind of shocking given the talent involved. Directed by Lawrence Kasdan from a script by Kasdan and William Goldman (in what what would proved to be his penultimate screenplay credit, followed only by the little-seen thriller Wild Card in 2015), Dreamcatcher is a prestigious, top-of-the-line production adapting the first novel King released after the 1999 car accident that left him grievously injured.

Though King is now dismissive of the novel, attributing his dissatisfaction to it having been written under difficult circumstances and the influence of painkillers, Dreamcatcher arrived at a kind of high-water mark for the author, when the critical appreciation for his work that swelled in the 1990s converged with the public sympathy stirred by nearly losing him to a careless driver. The film’s opening scenes are as adept at capturing the casual back-and-forth between characters that’s a trademark of King’s novels as any adaptation.* The four friends’s banter has the organic feel of edging-into-middle-age men trying to tease and outdo one another but without pushing the insults too far. If the plot resembles patched-together pieces of other King works—a little bit of childhood adventure from Stand by Me and It, some psychic abilities on loan from The Shining, and some inspiration from The X-Files, a show King admired enough to script an episode—that’s to be expected from later King novels, and can be part of the pleasure of reading them.

So why does it go off the rails? Winningly played by all four leads, the heroes make for amiable company before getting swept up in the business of a big-budget movie filled with all the special effects muscle a studio could offer in 2003. In Salon, Charles Taylor summed up the film’s central problem, and a problem endemic to that era of blockbusters, writing, “Dreamcatcher is a pretty good example of how the studios have taken over the junk that used to be left to the exploitation hacks. The hacks here have millions to work with and the end result isn't nearly as much fun as a cheap, gross horror movie can be.”

Henry, Jonesy, and the others find themselves doing battle not with a shadow-drenched puppet or stuntman in a rubber suit accompanied by an eerie and budget-friendly synth score but an elaborate-yet-not-that-impressive creation whose arrival is announced by blaring James Newton Howard cues. When the dying Duddits joins the action late in the film, he’s treated with messianic reverence. Beneath improbably bushy eyebrows, Morgan Freeman goes full Morgan Freeman on lines like “They drive Chevrolets, shop at Walmart and never miss an episode of Friends. These are Americans.”

The divide between the no-expenses-spared production values and elevated tone and a plot about aliens whose MO, as one character puts it, is to come “bustin’ out the basement door” is dizzying. Taylor’s not wrong that this might have worked better as low-budget schlock, but it’s hard not to admire the ambition accompanying the mismatch. By the time Dreamcatcher climaxes with an alien-on-alien fight scene by Massachusetts’ Quabbin Reservoir, it’s long since gone off the rails. But any off-the-rails journey that involves a side trip into a character’s Memory Palace, rendered as a cluttered, multistoried library/warehouse littered with files with names like “Jerk-Off Fantasies” and “Sports Humiliations,” is at least a memorable one.

That might be a long way of saying I miss an era when this sort of disaster still felt possible, that a movie could be not just poor but spectacularly, almost admirably awful. Every once in a while, a film like 2o19’s Serenity or 2016’s Passengers will provide a throwback to this kind of grand-scale miscalculation, but truly bad movies, the sort that can only be made by smart people make bad decisions and seeing them through to the end, have given way to the dullness of superhero mediocrities and other forms play-it-safe IP adaptations. (Even most of the King adaptations we’re getting these days are second-time-around takes on books that have been adapted before.) We live in a time of too many turds, and not enough shit weasels.

* I’ve read a lot of King, but I have to confess here that I have not yet read Dreamcatcher.

Me always wonder why one cavalcade of insane ideas becomes disaster like this, and other cavalcade of insane ideas become masterpiece like Sorry To Bother You or Everything Everywhere. Because on either side, you have to have people making movie convinced it going to be brilliant, and people worried it going to be unwatchable mess. Me wonder what fulcrum is that make one group turn out to be right or other.

One extratextual thing that I wouldn't bring up except it was the reason my dad and I saw the movie: this was also what Warner chose to put the Final Flight of the Osiris Animatrix short in front of as marketing leading up to Matrix Reloaded.