Dialogue: 'Macbeth and the Movies': Part 3

Our 'Macbeth' project comes to a close with Joel Coen's new 'The Tragedy of Macbeth,' a few words on 'Scotland, PA,' and the esteemed Macbethie awards.

In the lead-up to Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, slated for limited release this Christmas and Apple TV+ on January 14th, we wanted to have a conversation about the most significant attempts to bring “the Scottish play” to the biggish screen. That exchange will run in three parts. Last week we discussed Macbeths from Orson Welles and Akira Kurosawa’s Macbeth-inspired Throne of Blood. Up for discussion this week: the new Joel Coen adaptation with Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand, the Macbeth-inspired 2001 comedy Scotland PA, and final thoughts on the project.

Scott: So we’ve finally reached the main event, Keith: Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, which comes out in theaters on Christmas Day (fun for the whole family!) before debuting on Apple TV+ on January 14th. I first saw a screening of the Coen before watching or re-watching all these movies for our Macbeth conversation, and then I had the luxury of seeing it again, more familiar with the language and more cognizant of the major scenes and soliloquies that distinguish one adaptation from another. And I have to confess, I came away from a second viewing with a somewhat diminished opinion of it. This almost never happens to a film with the Coen name attached. (As multiple people have joked on Twitter, the film suggests that Ethan was the funny one.)

Watching it this time, I couldn’t help but to recall a line from our editor Alan Scherstuhl’s review of Justin Kurzel’s Macbeth, in which he said it would “enjoy a long post-theatrical afterlife of not being much help for high school students.” Not so, Coen’s Macbeth. Of the adaptations we’ve seen, this is definitely the one that you could show to high school students—you can almost hear the rolling of the TV cart down the hallway. That’s not entirely meant as an insult—faithfully adapting one of the great works of Western literature isn’t the worst strategy—but as a viewer, you do hope for a take on the material that feels in some way inspired and distinctive, and this Macbeth, while impeccably crafted and generally solid, feels weirdly timid and under-imagined for a Coen production.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

Some of that is owed to the visual conceit, which is extremely stripped-down and low frills, not unlike Orson Welles’ unadorned, B&W version, though Welles does more with his borrowed sets and signature low-angle camerawork. The minimalism of The Tragedy of Macbeth—which is quite beautifully rendered, we should say, by cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel, who shot Inside Llewyn Davis and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs for the Coens— seems intended to emphasize the performances, because when there’s nothing much else to look at, your eyes are fixed on the actors.

On that front, the film seems like a bit of a mixed bag. Denzel Washington is one of the greatest actors alive, so seeing him take on Shakespeare is a rare treat, and he’s quite good in the role, even though at times his readings seemed weirdly disconnected with the material. His “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” soliloquy, recited dramatically as Macbeth descends a flight of stairs with his dead wife below, seems conspicuously removed from the despair that usually attends it. But Frances McDormand as Lady Macbeth is outright bad. She’s a brilliant actress, too, but in both viewings her style has struck me as incompatible with Shakespeare’s rhythms, and her big moment, the “out damned spot” soliloquy, is a disappointment. It’s like the opposite of Marion Cotillard in Kurzel’s version: You don’t get any sense that she registers the deep shame, regret, and sadness of a woman who’s about to end her life. The points of emphasis in the speech are all over the place. Other performers in the cast are quite strong, however, and maybe you can help me cite some of those. (Kathryn Hunter as “the witches” is an obvious standout, and it happens to be the sole example of Coen bringing a thrilling new innovation to the table.)

What did you think, Keith? Am I being too hard on it? Keep in mind, I would give the film a passing grade overall, because it’s a quality rendering of a fine play. And you can see why Coen was interested in doing it: The entire “out damned spot” soliloquy is the theme of Blood Simple and many Coen films afterwards, so this feels like a return to First Principles. But am I wrong for expecting more from Joel here?

Keith: I wouldn’t say you’re being too hard, but you might be underselling some of its better qualities. I like this movie, but when I first heard a Coen—and, hey, if you can’t get two, one’s still pretty promising —was adapting Macbeth with Washington in the lead role I braced myself for an all-time great take on the Scottish Play. This isn’t that. There are remarkable elements within it, but it never really coheres into a truly remarkable film.

You’ve named some of those elements already. I like Washington as a muscular, strong-willed Macbeth. The character can sometimes feel wishy-washy and indecisive, a man pushed almost against his will by the ambition of his wife. Washington lets you see him seethe as Brendan Gleeson’s Duncan talks about who’s next in line for the throne. And he remains driven to the end. That final showdown with Macduff is one of the film’s most excitingly staged sequences, and I gasped when (spoiler for those unfamiliar with the source material) Macduff’s sword struck Macbeth’s neck and the crown went flying. I also liked the look of it quite a bit. You’re right to cite Welles’ adaptation as the closest comparison to Coen’s, in part because neither tries to be a realistic-looking film. We’re in a Shakespearean dreamspace here, one in which swordplay, witches, and ghosts can live side-by-side. And Hunter’s witch(es) is/are quite haunting, made all the more so by Coen’s staging. (Love that reflective pool.)

And while you’re not wrong that this will likely be sophomore English classes’ Macbeth of choice for years to come, Coen does make some bold choices. He builds on Polanski’s idea of using Ross as a behind-the-scenes manipulator, essentially positioning him as the Shakespearean equivalent of Littlefinger playing both sides against one another while moving events along in ways only he can see. (What did you think about the moment that suggested he might have killed Lady Macbeth? That kind of changes up the rest of the play, doesn’t it?)

You’re right that this isn’t McDormand’s finest moment. I don’t think she’s awful, but there aren’t any surprises here. If you asked me to imagine a McDormand Lady Macbeth before seeing the movie, this is pretty much what I would have pictured: a little tetchy, a little nervous, a little scary.. Lady Macbeth is a Mt. Everest of roles, and McDormand seems content to hang out at one of the base camps.

Her casting, however, does point to one of the more intriguing choices here. While making it clear that Washington and McDormand are vibrant, attractive people in real life and exude these qualities on screen, they are also both in their mid-sixties. Polanski felt the Macbeths had to be young and ambitious for Macbeth to work. Coen opts for a murderous couple well on the other side of youth, which makes their childlessness all the more conspicuous. They’re never going to produce an heir. All they have is a desire for power, power that they won’t even be able to hold for long before the clock slips away. Macduff, by contrast, is played by the 33-year-old Corey Hawkins and, as Macduff often is, portrayed as a clear-eyed embodiment of righteousness. The age difference turns Macbeth into a story about aging leaders with heads full of bad ideas grasping to hold onto the reins of the world, refusing to get out of the way for the next generation, and tearing society apart in the process. I don’t see a lot that ties Coen’s Macbeth to the current moment, but this connection feels pretty significant.

Am I overthinking this? And I’m curious where you see the Coen stamp here. I feel like, taken in bulk, the Coens’ movies offer a decades-long exploration of greed, ambition, and the consequences thereof. Those themes are all over Macbeth, but I expected this to feel more of a piece with previous Coen films than it does. Am I wrong?

Scott: I love your insight about the significance of the actors’ ages here, because I couldn’t get past the narrow thinking that Coen simply wanted to cast the film as a vehicle for his wife, McDormand, and Washington, an actor he’s never worked with previously. The idea of Macbeth not having an heir to the throne he’s seizing—per the prophecy, Banquo’s children would make that ascendency instead—drives his actions in the play and leads him to want to kill not only any challengers to his rule but also anyone who might take over after he dies. The last two presidents we’ve elected in America are two of the oldest—the current resident of the White House is the oldest, in fact—and will not live to see, say, the devastating impact of climate change. How can you feel invested in a future that won’t have you in it? As we’ve seen, it can keep leaders from listening to the young, and even embracing a kind of a nihilism, as if their generation will be the last.

As for its connections to other Coen films, I concede they’re mostly thematic, but once Macbeth encounters the witches and shares their prophecy with his wife, Macbeth echoes a familiar Coen Brothers story about a poorly thought-through criminal scheme that goes terribly awry. Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Fargo, The Man Who Wasn’t There, The Ladykillers, No Country for Old Men, Burn After Reading. You can add The Tragedy of Macbeth to that long list, and perhaps you can connect the B&W photography to The Man Who Wasn’t There—that film references post-war noir and this one evokes German expressionism,a primary stylistic influence on noir. But this one is unique in that the scheme as it’s about the acquisition of power, rather than a crime of passion (e.g. Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, The Man Who Wasn’t There) or money-making endeavor (e.g. the rest of ‘em).

Yet the Coens were always interested in the terrible things that can happen after a person (or persons) make that initial decision to cross the line. Hi and Ed in Raising Arizona thought Nathan Arizona wouldn’t miss one of his bounty of quintuplet sons. Jerry Lundegaard in Fargo hired men to kidnap his wife so he could bilk his father-in-law out of “a little bit of money” and surely did not expect any casualties, much less the absurd pile of bodies that winds up littering the highways, lakefronts, and parking decks of Minnesota. The fitness center dopes in Burn After Reading thought they could score blackmail money out of a CD they found in a locker room. Obviously, the Macbeths’ first step is more violent, in that they have to murder Duncan and pin the crime on his guards. But, in that Coen way, they don’t anticipate what they might be compelled to do after the scheme is underway.

Maybe my mild disappointment with The Tragedy of Macbeth relates to my expectation that Coen would shake up the material more than he does, perhaps adding elements of black comedy or a more audacious tweaking of the text. But you’re turning me around a little on Coen’s more subtle points of emphasis—the ages of the Macbeths, Ross as a player more consequential than mere messenger, the vigor of that climactic duel. This is a Macbeth for our times, no doubt, and there’s enough connective tissue to make it a meaningful part of the Coen story.

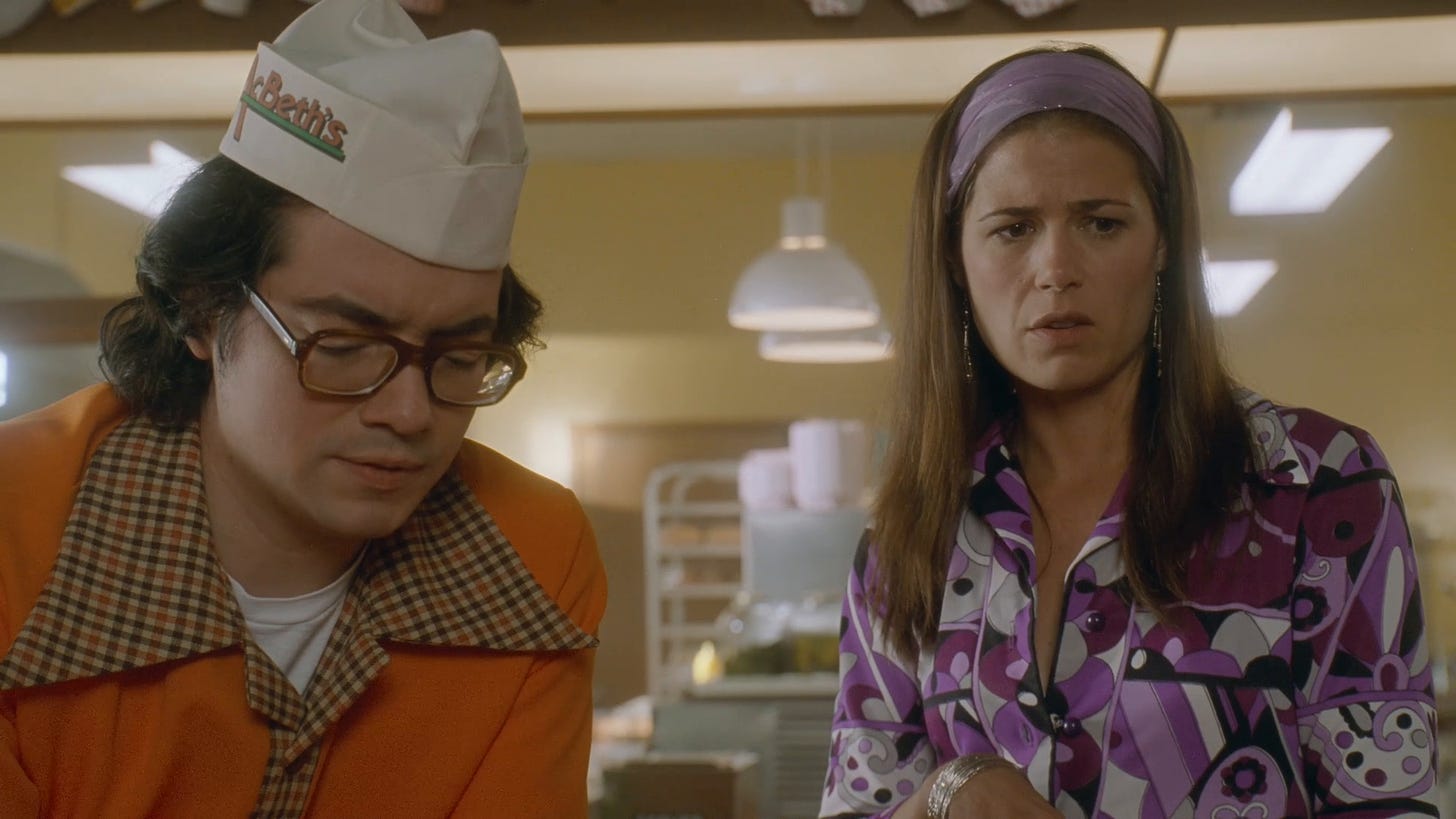

Now, we promised the people a few words on Scotland, PA, an irreverent goof on Macbeth from 2001 that picked up enough of a cult following to inspire an acclaimed musical two years ago. What did you think of it?

Keith: Eh. On second viewing I’ve warmed up to it a bit with time but I went back and read my, good Lord, almost 20-year-old review at The A.V. Club, and I can’t disagree with that kid too much. It’s a film with a single joke—hicks in the sticks play out the plot of Macbeth at a burger restaurant—stretched to the breaking point. But it has a great cast of favorite character actors like James LeGros, Maura Tierney, Christopher Walken (who’s super-fun as a New Age-y Columbo who hates meat) and a babyfaced Kevin Corrigan, plus some clever ideas and good lines, including Tierney’s Lady Macbeth’s explanation of why they had to commit murder because they were thritysometing “underachievers who have to make up for lost time.” But a lot of it still grates, like Andy Dick, Timothy “Speed” Levitch, and Amy Smart’s “witches,” and it just goes on forever. (I did chuckle whenever a Bad Company song came on the soundtrack, however, after reading director Billy Morrissette’s explanation that the “the band's catalog was surprisingly inexpensive.”)

That said, don’t let me be a sourpuss who spoils the fun for others. I can see why it’s built up a cult. And it also speaks to the transplantability of Shakespeare. We’re drawing this project to a close but we could have kept going. I previously mentioned Joe MacBeth, the British crime film set in the American underworld we could not track down. Geoffrey Wright directed a version in 2006 set in the Melbourne underworld (and starring Sam Worthington as Macbeth) that I don’t think ever came out in the States. And I tried to get you to watch the 1990 obscurity Men of Respect, in which John Turturro plays a Macbeth figure working his way through a New York mafia whose members include Rod Steiger, Dennis Farina, Peter Boyle, Stanley Tucci, and features Katherine Borowitz (Turturro’s real-life wife) as its Lady Macbeth. I didn’t push that hard however. I rented it on a whim 30 years ago and I don’t remember it being good in spite of that cast (though making its “witches” the hosts of a cooking show is a clever touch that stuck with me).

Still, I’m very pro weirdo Shakespeare transplants. And pro Shakespeare movies in general. This has been a fun discussion, and I’ve especially liked charting how small changes have ripple effects throughout the movies. The dead kid at the beginning of Kurzel’s version—an addition nowhere in the text—pretty much defines the Macbeths and why they do what they do. I hope we can do this again sometime. Scott, any last words before the curtain falls?

Scott: To borrow one of my most-used Coen quotes, via Burn After Reading, “What did we learn, Palmer?” I hope the answer isn’t “I guess we learned not to do it again,” because this has been fun.

I think I’m with you on Scotland, PA, which stretches itself awfully thin in trying to incorporate elements from the play into a milieu that doesn’t accommodate it that easily. We’ve seen how adaptable Romeo and Juliet has proven to be: Its warring families and star-crossed lovers have accommodated many different eras and conflicts between classes, ethnicities, and entire nations. Bringing Macbeth into the modern world isn’t as comfortable a proposition, and using the “Mac”—or in this case “Mc,” as in McDonald’s—to situate the story in the fast-food world sounds like the type of “eureka” moment an artist has when completely baked. But it’s a smart idea nonetheless, and I appreciated the low-key modesty of the whole affair, with its emphasis on local color, the wonders of the drive-thru concept, and a cast of indie stalwarts who ping off each other nicely. Walken’s McDuff steals every scene he’s in, of course, and the film inserts Shakespeare at unexpected times. The scene with Banquo’s ghost (or “Banko” here, played by Corrigan) doesn’t happen until much later in the story, and the way Tierney’s Lady Macbeth ultimately deals with her hand is an inspired twist on Shakespeare’s soliloquy-and-suicide combination.

To me, the Macbeth project has been a welcome chance to dig deeper into the play and appreciate how different adaptations reflect their director’s sensibility and obsessions. Orson Welles, Akira Kurosawa, Roman Polanski, Justin Kurzel, Joel Coen—these filmmakers all are known for their audacity, and there’s not one version of Macbeth that feels stuffy or under-imagined, even if watching the Coen could help future students toward an “A+” on their exams. We’ve seen Macbeths both passive and angry, and Lady Macbeths both sinister in their machinations and crushed by regret. We’ve seen adaptations that care deeply about the play’s historical setting and others that take place in sparer and more theatrical backdrops. But in every case, we’ve been confronted with a grim lesson in hubris and moral decade, as a lust for power leads a once-great man to acts of gruesome treachery, corruption and, finally, self-immolation.

Before we wrap up, I present to you The Macbethies, my choices for the finest films, performances, and moments in the six Macbeths we saw:

Best Film: Throne of Blood

Best Macbeth: Toshiro Mifune (runner-up: Orson Welles)

Best Lady Macbeth: Marion Cotillard (runner-up: Isuzu Yamada)

Best Macduff: Sean Harris (runner-up: Christopher Walken)

Best Witches: Throne of Blood (runner-up: The Tragedy of Macbeth)

Best “tomorrow and tomorrow” soliloquy: Welles

Best “out damned spot” soliloquy: Cotillard

Best movement of Birnam Wood: Justin Kurzel’s Macbeth

Best utilization of beloved character actor Kevin Corrigan: Scotland, PA

Keith: Can’t disagree with any of the above, especially that last one. (Though, as much as I liked Stephen Root’s turn, you could drop Corrigan into the Porter role in the Coen version, couldn’t you?) So when shall we two meet again? (Probably pretty soon, I’m guessing.)

While I think there is weakness in McDormand making the transition to “wracked with guilt Lady MacBeth”, I really loved her “ambitious Lady MacBeth”, so I found myself overall enjoying her performance more than either of you. Can’t agree more about Washington inadequately selling “tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow” however; while out of the purview of your series, nothing tops Ian McKellan’s go at it:

https://youtu.be/4LDdyafsR7g

Loved this series, though I worry that you've brought about 100 years of bad luck to your site...

Sneaky Macbeth supplemental: I just finished reading "All's Well" by Mona Awad, a darkly comedic novel about a university production of one of Shakespeare's frothier plays (you can guess from the title) after the director, shocking and dismaying everyone, decides not to do the Scottish play. The book is a kind of magic realist tug-o-war between the two, as elements from the latter end up colouring the former and the director becomes a mix of Lady M and Faust (to throw in yet another influence). This one's a stretch as an adaptation, but well worth a look. The Three Weird Brethren are about as delicious as it gets.