'Devil in a Blue Dress': When the Wrong Franchise Dies

In 1995 Carl Franklin delivered a superb adaptation of a Walter Mosley mystery novel. It should have been the first of many.

The ’90s are littered with potential film series that couldn’t go the distance. The Shadow, Judge Dredd, Wild Wild West: none of these were meant to be one-and-done movies. They were meant to spawn sequel after profitable sequel. But while the world of film isn’t really poorer for the loss of, say The Phantom 2, not every dead end is deserved. You can watch this space for an inevitable appreciation of The Rocketeer one of these days. But there’s no greater what-could-have-been among would-be franchise starters than Carl Franklin’s Devil in a Blue Dress. Recently re-released on 4K, Blu-ray, and DVD as part of the Criterion Collection, the film should have kicked off a long series of stylish noirs that doubled as a cultural history of a changing Los Angeles told from the perspective of a Black hero who keeps bumping against an invisible but fortified racial divide. Instead we got only one.

It’s both a compensation and a source of frustration that Devil in a Blue Dress is as good as it is. Denzel Washington stars as Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins, an airplane mechanic trying to make a living in post-war Los Angeles who loses his job in an early scene that tells us a lot about our hero without spelling it out. Speaking to the white boss who’s letting him go, Easy’s mindful of the power dynamic and he’s deferential without losing his dignity — but only up to the point where there’s nothing to be gained by deference. Then he lets his frustration boil over.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

As in the mystery novels by Walter Mosley that Devil in a Blue Dress adapts, Easy’s a skillful tightrope walker, but he’s also prone to take the occasional tumble. Strapped for cash, he goes against his better judgment and agrees to do some poking around for a shady character named DeWitt Albright (Tom Sizemore), who’s looking for a woman named Daphne Monet (Jennifer Beals), the disappeared fiancée of a wealthy mayoral candidate. Easy’s hired because he can go places Albright and his men cannot, namely the Black nightclubs Monet frequents, driven by what Albright calls her taste for “jazz, pigs’ feet, and dark meat.”. Of course, this being a twisty noir in which nothing is quite what it seems, there’s more to the story.

And, as with the best noirs, the plot invites the detective and viewer both to tour the complex dangers, pleasures, and truths of an unjust society. Easy’s journey takes him from the top of the L.A. social sphere (which requires him to sneak into a “whites only” hotel after dark) to the lower reaches, where he’s more welcome but no less imperiled.

Washington plays Easy as a man whose ability to code switch has helped keep him alive. Hanging out in a jazz club, he’s relaxed and sociable, a contrast to the tightly coiled Easy seen in neighborhoods that aren’t his own. In a kind of sequel to his tense exchange with his white boss, Easy tries to steer out of a conversation with a young white woman on a Malibu pier, an exchange he didn’t start and is eager to end even before the drunken louts accompanying harass him for talking to a white woman. But even when he does everything “right” according to the rules imposed upon him by his world, he can’t avoid violence.

That’s a passing moment that doubles as a snapshot of life in a racially divided city, a Los Angeles Franklin brings to rich life. Working with a production team that included Jonathan Demme (he uses the deft cinematography of Demme regular Tak Fujimoto here), Franklin acquired the rights to the first three installments of Mosley’s series with the intent of filming them all. Devil in a Blue Dress is complete and satisfying in its own right. But it’s also an origin story that sets the stage for what was supposed to come.

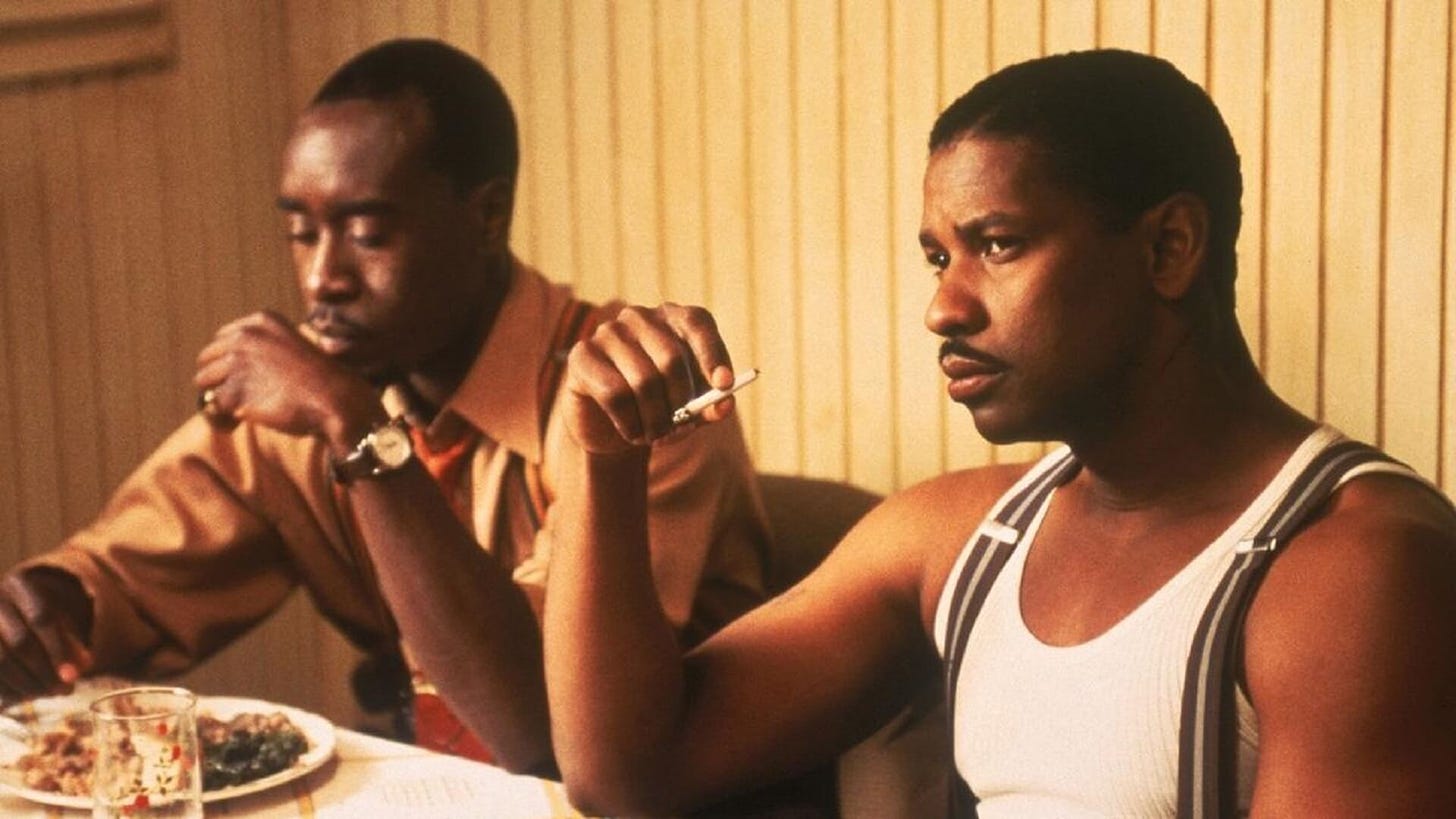

“With his Champion Aircraft jacket and work shirt he is everything but a film noir detective, which was part of the way we turned the film noir on its ear,” Franklin says, speaking to Blue Dress co-star Don Cheadle in a conversation included on the Criterion release. “Philip Marlowe, of course, would have been cynical and been much more at home in this world. But this was the story of a character becoming a detective, of becoming cynical.” The film ends with Rawlins managing to hold onto the home he sees as a foothold, however tenuous, in the post-war American boom that often left its Black citizens behind, and with him pondering a new career as a detective.

It also sets up a supporting character who, for all Washington’s movie-star magnetism, almost steals the movie. About Cheadle: I know I’d seen him before Devil in a Blue Dress, but I don’t know that I’d ever really seen him. As Mouse, Easy’s friend from back in Texas, Cheadle shows up mid-film to save Easy from certain death. But his arrival also introduces a threat of a different kind. Sharp-dressed and short-tempered (and sharing a dark history with Easy that’s alluded to here but never fully explained), Mouse explodes in violence at the slightest provocation, even threatening Easy in a moment of frothing rage. He’s a difficult, unstable character but also a man who knows exactly who he is. “If you ain’t want him killed, why did you leave him with me?” Mouse tells his friend after dispatching a bad guy Easy wanted left alive. It’s hard to argue with his logic, harder still not to chuckle while still feeling a chill from his scary conviction.

Mouse returned, sometimes at inopportune moments, in Mosley’s very good follow-ups to Devil in a Blue Dress, installments that furthered Easy’s story while dropping him into mysteries in the changing L.A. of the 1950s and 1960s. (It’s a work in progress, too; the most recent entry, Blood Grove, was published just last year. I fell off reading them at some point but revisiting this film made me want to catch up.) But as good as those stories are on the page, it’s a shame the Franklin / Washington / Cheadle team never got a chance to bring Easy and company life on screen again.

Devil's reputation has grown and grown over the years, so it’s kind of shocking to recall how tepidly it was received at the time. Released at the tail end of September — the same weekend that saw the debuts of Se7en, Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers, and The Big Green — it debuted in the weekend’s third slot. Kind but less-than-rapturous reviews didn’t help, with some critics objecting to a kind of chilliness that, to my eyes, feels appropriate to the genre and to the story of a man forced to visit spaces in which he can never quite be himself. “The movie seduces the brain but not the heart,” Rene Rodriguez wrote in The Miami Herald. “I liked the movie without quite being caught up in it,” Roger Ebert commented in his Chicago Sun-Times review.*

Recalling the release, Franklin notes that the film was unaided by the departure of the TriStar execs who championed it and the niche appeal of film noir in general, even one starring Denzel Washington, saying, “film noir is for people who just like cinema.” Maybe. But it’s hard not to feel like Devil in a Blue Dress should have been the start of something rather than its end. At least it’s still there for those of us who just like cinema to discover or revisit, and to appreciate it for what it is while sparing a thought for what it might have become.

Devil in a Blue Dress is newly released on 4K, Blu-ray, and DVD by the Criterion Collection. It is also currently streaming on HBO Max through the end of the month and available to rent through the usual VOD services.

* Ebert was a big champion of Franklin’s directorial breakthrough, the noir-inflected crime thriller One False Move. In an interview included in the Criterion edition, Franklin starts to tear up recalling how Ebert and Gene Siskel saved the film from obscurity.

Regal just made a Facebook post asking what movie deserves a sequel that doesn't have one, so I made sure to drop a link to you guys and call out Devil in a Blue Dress, which is almost always my answer to that question anyways.

I still haven't lost hope for a belated sequel, even if it's not a film. Franklin has been out of the feature game for a while, but he's found a niche in noir-ish television and Mosley's series seems tailor-made for the modern streaming landscape. You have to think there's a pitch sitting on somebody's desk, right? The bigger question might be, would Denzel make the jump to the small screen?