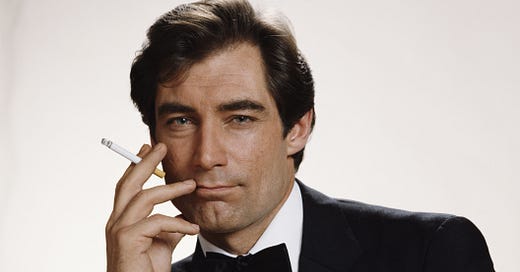

Dalton, Timothy Dalton: Agent Double-O Gen X

A look at the short reign of the perfect Bond for a generation that’s fallen between the cracks.

Roger Moore didn’t say goodbye to James Bond with A View to a Kill, the 14th entry in Eon Productions’ Bond series. His goodbye came two years later with Happy Anniversary 007: 25 Years of James Bond, a primetime special that aired on ABC in May 1987 in which Moore introduces highlights from the first quarter-century of Bond movies. Moore grins his way through the cheesy Bond-inspired vignettes that set the scene, ordering a specific vintage of wine (from 25 years before, of course), dodging shady characters at a train station, and stroking a Persian cat presumably stolen from Blofeld. Then he exits, and it’s another announcer whose voiceover announces the segment that will end the special: an early look at the actor who would take Moore’s place: Timothy Dalton, whose first film as Bond, The Living Daylights, would premiere just a few weeks later. After a final hour of Moore’s smirking charm, it was time for something new.

Over three decades and a couple of Bonds later, it’s easy to forget what a big deal Dalton’s debut was at the time. New Bonds came around less frequently than new Popes. Factoring out projects not made by Eon — the production company founded by Albert “Cubby” Broccoli and Harry Satlzman, then passed to the team of Cubby’s daughter Barbara and stepson Michael G. Wilson, who continue to run it today — only three actors had played Bond at this point: Sean Connery, George Lazenby, and Roger Moore.

Fans tended to fall into either Connery or Moore camps, which could be a matter of age as much as taste. (There was no Lazenby camp.) It was hard to deny that the Connery run, on the whole, produced better films or that Connery, at least in his earlier outings, gave a more thoughtfully considered performance. But if you grew up in the Moore era, Moore likely was your Bond. In 2002, The New Yorker’s Anthony Lane likened that experience to “being too young to remember the first moon landing but old enough to get into the later missions, with their golfing larks and trips in the Lunar Rover.” Any sense of danger or edge might have disappeared but, gee, it sure looked fun anyway.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

I was (and remain) a Moore fan, which means constantly justifying an obvious lapse in judgement. But seeing Octopussy in the theater at 10 remains one of my formative moviegoing experiences. It was the first time my parents ever dropped me off at the movies alone, and for two hours I thrilled to the quips, explosions, fast-moving vehicles, and bared flesh a kid inching toward puberty could want (and as juvenile as it was, it did feel somehow more adult). I imprinted on Moore’s Bond, my tour guide to that world, with the guilelessness of a duckling.

But by 1987 even I was ready for something new.

Generation X, a demographic into which I fall into almost the exact mathematical middle, inherited Moore, and by the mid-’80s he was looking ready for retirement. Even Moore admitted it, telling the authors of Taschen’s gargantuan The James Bond Archives, “When they start running out of actors old enough to look as though they could be knocked down by bone, and leading ladies are your mother’s age when you started making Bond, then it’s time you move on.” That A View to a Kill had underperformed at the box office probably helped make his decision easier. Moore had toyed with leaving the series, which he had joined in 1973, for years, playing a game of brinksmanship with Eon each time his contract was up. Now he seemingly realized he’d played that game as long as he could. His exit would allow room for a Bond a new generation could truly call its own.

Enter Dalton, who recalled being approached by Broccoli about playing Bond twice before, once as a just-starting-out actor in 1968 and again in 1980, when it wasn’t clear if Moore would return. Winning the part meant competing with everyone from Sam Neill to the now-forgotten Australian model Finlay Light. It also involved getting lucky when Pierce Brosnan couldn’t take the role due to contractual obligations. “In terms of looks and style [Brosnan] would have taken us along the Roger Moore route,” Broccoli recalled after the fact. “At the same time we were looking for a harder-edged actor who could take Bond into a new direction.”

Dalton, a classically trained actor who’d worked steadily since the late-’60s, took the part seriously, reading and rereading Ian Fleming’s original novels and short stories in an attempt to connect with the original essence. “I was given the freedom to make Bond the character I saw, to capture what I believe to be the spirit of Ian Fleming’s James Bond,” he said. “For me, he clearly lives in the moment. He’s always on the edge of his own death, everything is weighted—touch, smell, taste. All these qualities, like the love of smoking, fast cars, drinking, and gambling are connected to who he is.” Dalton’s would be a Bond far more comfortable breaking jaws and throwing himself into near-suicidal situations than cracking a joke or seducing a woman — in the punchline to The Living Daylights’ pre-credits segment a woman seduces him before he's even really noticed her.. The Bond for the late-’80s, when those born when Roger Moore was the new guy now were turning into teens, would be grim and businesslike.

He would also ultimately become something more than a footnote but decidedly less than an era-defining Bond. Call it the Dalton interregnum, a stretch that’s half-forgotten yet impossible to erase from history — the perfect circumstances for Gen X to claim him as our own.

The May 14th issue of the New York Times contained a package of articles dedicated to Generation X that, for one day, put my contemporary’s old passions and cultural touchstones — from Benetton ads to Evan Dando — back in the spotlight. Then the media narrative shifted back to the generational struggle between Boomers and Millennials as those of us who had at least one, maybe two, chances to vote for Clinton receded back into the shadows with our comically large cups of overpriced cappuccino and our 3 Feet High and Rising CDs.

Though unmentioned in that package, Dalton is very much part of the same cultural stew, in part because the Dalton era of Bond feels so indeterminate. Such were the times. Not only did Dalton and the makers of The Living Daylights have to figure out who Bond could be now that he was no longer player by Roger Moore, they had to figure out how a character defined by the Cold War could fit into a world beginning to thaw, and how a character who bedded seemingly every woman he saw should behave when the AIDS epidemic made casual sex feel as dangerous as a hulking bad guy with big metal teeth.

The film solves the latter issue by keeping Bond borderline monogamous, pairing him with just one woman — the Russian cellist Kara Milovy (Maryam D’Abo) — after the implied coupling of that pre-credits sequence. The New World Order it mostly ignores. Released two years after the ascent of Mikhail Gorbachev, The Living Daylights still plays like the product of a pre-Glasnost age, tasking Bond first with smuggling a KGB general from behind the Iron Curtain then with teaming up with our friends in Afghanistan in the fight against the Soviet Union, the Mujahideen, an alliance that history has since cast in a different light. (See also Rambo III, released the following year.)

Journeyman Bond director John Glen never finds a way to make the action pop in the seemingly endless final act, but it’s otherwise a decent-enough Bond film — with a more grounded plot in line with the earlier Connery outings. Contemporary critics often didn’t see it that, however, sharing the weariness of People’s review, which concluded, “ Why not send James off to well-earned retirement with a gold-plated martini shaker and the thanks of a grateful moviegoing public?” Dalton proved particularly divisive. Both Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert each gave it a thumbs down, though Ebert saw promise in Dalton’s future, providing he developed the sense of humor Ebert felt essential to the role.

He did not. The Living Daylights was written for no actor in particular. Screenwriters Michael G. Wilson and Richard Maibaum half suspected Moore might even return. Its successor, however, was tailor-made to Dalton’s perceived strengths as a deathly serious Bond, and to the spirit of the moviegoing moment. “Drugs were an issue in popular cinema of the time,” Wilson said of the film eventually called Licensed to Kill (its title changed from License Revoked because, per Broccoli, MGM insisted Americans didn’t understand the word “revoked.”) It’s the closest Wilson comes to acknowledging that the film aspired not for the traditional tux-and-martinis sphere of Bond films but the grungier, sweatier world of low-budget ’80s action movies. License to Kill mixes graphic violence with a War on Drugs-friendly plot in which Bond takes out Central American drug lord Franz Sanchez (Robert Davi).

If that seems like small potatoes for an MI6 agent usually pitted against supervillains, at least it’s personal. Bond’s compelled to seek revenge revenge after Sanchez’s men (including a young-but-not-exactly-babyfaced Benicio del Toro) rape and kill Bond pal Felix Leiter’s wife on her wedding day and then dip Leiter into a shark-filled tank. It’s grim stuff, a lousy Bond movie, and about as fun as an abscessed tooth. But it’s also a stark cinematic artifact of its cultural moment. For the U.S. and Britain, the old enemies had faded, but the impulse to view every problem as a war to be won remained as strong as ever.

That ability to filter other aspects of history and culture through a Bondian lens is why even the weakest Bond films have value. If you want to know what 1979 was all about, the space disco adventures of Moonraker is a fine place to start. The Dalton Bond movies look confused and misguided, unsure where to send Bond or who he should be fighting, and they're anchored by a leading man who sometimes looks as if he’s in the midst of a final exam for which he hasn’t studied enough. But such was the spirit of the times. For a Gen Xer to revisit these movies now is to remember the nebulous moment in which we came of age, one in which the world, like Bond, had begun to change into something new, though it wasn’t yet clear what form that change would take.

Bond wouldn’t stay in the form of Timothy Dalton much longer. Though The Living Daylights became a solid hit, License to Kill performed underwhelmingly. “It was obvious Michael and I had to do some serious rethinking,” Broccoli said in the film’s wake. “We agreed that in making Bond an altogether tougher character, we had lost some of the original sophistication and wry humor. Bond was not a Superman, or a Rambo. He was the kind of guy who had tremendous will.” Still, Eon had plans to proceed with a third Dalton film until legal troubles between the company and MGM put the series on hiatus that wouldn’t end until the production of Goldeneye. Its release in 1995 marked the end of the longest stretch between Bonds since the series began.

That film starred not Timothy Dalton, who stepped away, but Pierce Brosnan, free to pursue the role now that his TV obligations were in his past. And it was down the Roger Moore route Bond went yet again, for better or worse. If, like science fiction, the golden age of James Bond is 12, Goldeneye arrived just in time to delight those born in 1983. Dalton had his brooding moment behind the wheel of the Aston-Martin, but that moment had passed. He belonged to a different generation, one that barely had time to figure out what he was all about before he was gone.

I should add that, like Connery and Brosnan, Dalton's had a really fun post-Bond career, which started almost immediately in THE ROCKETEER where he played an Errol Flynn-like Nazi collaborator. (Flynn almost certainly wasn't a Nazi collaborator, but the stories endured anyway.) He's really fun in HOT FUZZ!, too. (And I keep meaning to check out DOOM PATROL. I hear good things.)

Octopussy was also my intro to Bond (we had a copy of it in my house on the defunct RCA home video CED format...I must have watched it a million times). My older brother was a big Bond fan, and so it wasn't long before I had watched the whole series as a kid. Even then, I knew the Moore stuff was perhaps a bit iffy when compared to the the first handful of Connery films, but I loved them all the same.

But I was there for Dalton too, and he was the first Bond I saw in theatres. I remember liking The Living Daylights a lot, but but being less into License To Kill. For me, Dalton made a much larger impression in The Rocketeer, which was and is one of my favourite adventure movies. I also loved him as Prince Barin in Flash Gordon. While I wasn't all in on Dalton as Bond, I did like the fact that he seemed like more of a precursor to what Daniel Craig's bond would have more of an opportunity to flesh out: a harder edged, post-Cold War Bond. It's a much better take on the character than Brosnan picking up the cartoonish excess of the Moore films, without the specific Moore charm to elevate the hijinks.