Bowie on Film, Part 1: The Musician

Inspired by 'Moonage Daydream,' this three-part conversation will explore David Bowie's relationship with movies. First up: a bunch of films that feature Bowie being Bowie (and sometimes 'Bowie').

Inspired by Brett Morgen’s new documentary Moonage Daydream, we’ll be spending the next three weeks talking about David Bowie and the movies. This first discussion kicks off with some talk about Morgen’s film and expands from there, ending with a look at some of Bowie’s key music videos.

Keith: A week after seeing it, I’m still thinking about Moonage Daydream, a really remarkable — in IMAX as we saw it, at least — immersion into Bowie’s career, with one moment flowing into the other in the form of an extended montage set to Bowie’s music. I like it a lot and it’s, of course, the reason we’re doing this conversation in the first place, but it almost feels like a way to conclude a look at Bowie’s career rather than a starting point. Morgen’s not interested in context. He is interested in dropping viewers in the deep end of the Bowie pool and letting the sound and vision (reference made on purpose) wash over them. At points I tried to imagine how it would play to someone who doesn’t know anything about Bowie, and I can only imagine it would be unfathomable.

On the other hand, who is that person? Even if you’re not familiar with every point of Bowie’s career, you’ve probably come into contact with some part of it or another. And if not, you’re still living in a pop culture universe he helped create. His music has its share of direct descendants but even more pervasive is the idea of pop stardom as a series of costumes and poses and career phases as skins that can be shed once outgrown.

I think Morgen’s film captures that quite well, both in the moments and songs it chooses to spotlight and in the Bowie interview snippets, particularly the more reflective moments from later in his life when he had some distance and the clarity that comes with sobriety. It’s easier to explain yourself when you’re not living on a diet of milk and cocaine, as he did for one stretch in the early ’70s (one captured in the BBC doc Cracked Actor, which Moonage Daydream frequently mines and which we’ll talk about below). This is a project sanctioned by the Bowie estate but it’s not purely a promotional tool for the Bowie legacy. There’s real insight here, even in the middle of a film designed to overwhelm. What did you think?

Scott: [*takes protein pills, puts helmet on*] We saw this film together last week in a faux-Max theater that was plenty big-and-loud for this experience, and I was mostly thrilled. When we were leaving, you said something to the effect of, “This is a film where you exit feeling like you know less about Bowie than you did going into it.” I get that line of thinking, in that you really are treated to an experiential, context-free journey through Bowie’s work, without much orientation in time or even a cohesive sense of when one period of his career ends and another begins. This is mostly to the film’s favor, in my mind, and I actually dispute your assertion that it’s like throwing Bowie neophytes into the deep end. This isn’t biography. It’s a conversion experience.

My excitement for Moonage Daydream relates to my enthusiasm for Morgen’s work, specifically the way he’s pushed the boundaries of nonfiction through editing technique. Morgen was responsible for the best and most audacious episode of ESPN’s 30 For 30, June 17th, 1994, in which he presented a astounding, surreal day in sports through a montage of broadcast footage, with no talking heads. That was the day that O.J. Simpson fled the police in his white Ford Bronco, Arnold Palmer played his final U.S. Open round, the FIFA World Cup landed in America, the New York Rangers celebrated a Stanley Cup win on Broadway, and more. More pertinently to Moonage Daydream, Morgen also made Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, a brilliant and moving assemblage of Cobain’s home movie footage and other bric-a-brac from his life that accounts for his triumphs and tragedy as well as any work I can recall.

There’s no attempt here to turn the footage offered by the Bowie estate into anything like Montage of Heck, which makes you feel like you’re watching Cobain the child as the father of the man. It’s not emotional in the same way. What it feels like to me is closer to one of those Pink Floyd Laser Spectacular shows, where people get stoned and stare up at the lights while Dark Side of the Moon plays in full. As a vibe, this feels more like cocaine than weed, but Morgen puts Bowie’s music and performance footage amid an associative rush of other images from movies and TV. A week later, it all seems like such a blur that I’m failing to sort out pieces of the movie—which may ultimately be a mark against it. But back to what you were saying about what Moonage Daydream teaches us (or doesn’t), I’m reminded of Bill McKibben’s book The Age of Missing Information, in which he compared a day’s worth of cable TV (100 channels, 2400 hours of programming) with a day he spend on a mountaintop near his home. This doc may be a rush of visual information, but it’s the mountaintop of this scenario: You get a fine attempt to capture Bowie’s essence, which may teach us something more valuable about him than a more straightforward biography ever could.

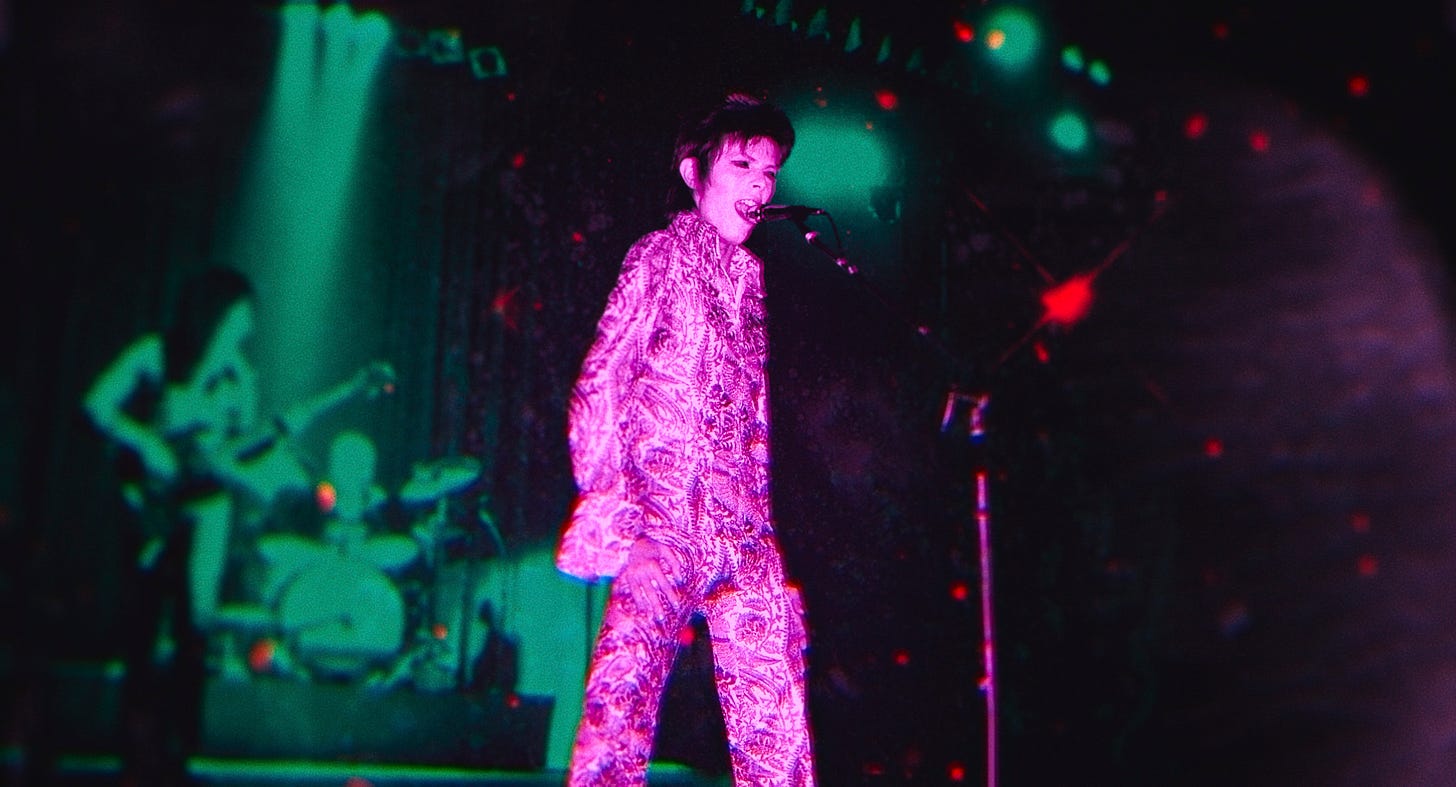

But Moonage Daydream certainly isn’t the first crack documentary filmmakers have had at Bowie, which might also account for Morgen’s decision to flaunt convention. I recently caught up with D.A. Pennebaker’s 1979 doc Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, which catches Bowie on the tail end of his Ziggy Stardust phase. The film has nothing like the reputation of Pennebaker’s classic Bob Dylan doc Don’t Look Back, and we can discuss why. But I’m curious to know what you make of it.

Keith: Despite admiring Bowie and Pennebaker, I’d avoided Ziggy Stardust and the Spider From Mars in part because it doesn’t have the reputation as Pennebaker’s best work or as a particularly great document of a Bowie doc. I think I can lay the blame, once again, on Leonard Maltin’s movie guide, which gave it 1 ½ stars and called it “practically unwatchable, and unlistenable: cinema verité at its worst.” (It’s kind of amazing how deep an impression some of those reviews made on me.)

It’s certainly not unwatchable or unlistenable. That’s silly. And this is an historic concert: the end of the tour, effectively the end of the Spiders, and the end of the line for Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust persona. But it’s not a great concert movie. Pennebaker has said he was understaffed—it shows— and the sound mix we now have, after years of fussing with it, remains merely OK. In spite of the talent involved, it’s definitely of a piece with too many uninspired concert films from the pre-Last Waltz age.

Still, I’m glad the film exists. It offers an extended look at Ziggy-era Bowie at work that we don’t really get anywhere else. That look has become so familiar from still photographs — Bowie was a well-documented rock star — and so influential that it’s easy to lose sight at how shocking it was at the time. One day you’ve got James Taylor plucking away about his feelings. The next you’ve got an androgynous space alien wearing one outrageous costume after another. I found myself especially struck by the clash between masculinity and femininity every time Pennebaker shot Bowie’s thighs. Here’s this delicate creature, elusive, fey creature atop these rippling tree trunk legs.

What about you? Did any particular moments stand out? I was struck by the backstage footage in which Bowie prepares and the quiet, turned-off backstage Bowie seems miles removed from the one who takes the stage, and also the performance moments that called on his skills as a mime who trained under the famed Lindsay Kemp (who also instructed Kate Bush).

Scott: I read a review of Ziggy Stardust that essentially said that the backstage scenes destroy the fantasy of Bowie’s persona and performance, and I could not disagree more, though I do wish these scenes were longer and more substantive. Pennebaker opening with Bowie sipping on coffee while getting his make-up done is a compelling image, because we can see the line that’s drawn between Bowie the androgynous, boundary-pushing artist and a guy who puts his spangly, form-fitting alien costume one leg at a time, just like the rest of us. I’d have loved to hear more of the conversation he has with Ringo Starr, though, or really anyone at that moment. For the end of a famous tour, Pennebaker makes it seem like this went out with a whisper, not a bang.

I don’t know if I can cite many highlights, other than the pleasure of hearing these great songs in the context of a final performance. The production stories around Ziggy Stardust make you feel for Pennebaker, given how underfunded and understaffed he was, not to mention the uncertainty of how (and at what length) it would ever get released. To state the obvious, the film looks as cruddy and unplanned as Scorsese’s The Last Waltz has every camera move and close-up planned to the note. (Yes, Scorsese had many times the production resources.) Maltin’s sideswipe at vérité annoys me, because it implies that vérité filmmakers are artless, but I acknowledge that Ziggy Stardust is haphazard and oddly stiff. There’s a nice moment when Pennebaker lingers on a woman in the crowd who’s crying during “Space Oddity,” and I felt like I wasn’t getting enough similar evidence of Bowie’s power.

But maybe that was the reality of the situation. Perhaps Bowie was already molting the skin of Ziggy Stardust and looking ahead to the next conceit that would energize him. Even amid the murk, however, you can’t resist a setlist this loaded—”Oh You Pretty Things,” “Moonage Daydream,” “Changes,” and “Space Oddity” all come one after the other, and you get covers of “Let’s Spend the Night Together” and “White Light/White Heat”—or the historic, if confusing, announcement that the tour and the band were over after that night. (Rest assured, Bowie had more to give.) Seeing some of these images processed through the Cuisinart of Moonage Daydream made them pop, too. It’s not a perfect snapshot of a moment, but it’s legible enough.

The Ziggy Stardust movie was new to me, as was the 45-minute Cracked Actor, which our readers can track down on YouTube. What does that film teach us about the Thin White Duke?

Keith: Scott, Scott, Scott: this is pre-Thin White Duke! You have to get your Bowie personae timeline straight. The Thin White Duke would not be introduced until the 1976 album Station to Station. Most of the concert footage here comes from the end of what began as the Diamond Dogs Tour (with elaborate sets used to bring the world of that George Orwell/William S. Burroughs-inspired concept album to life) and ended as the Soul Tour, with an increasingly funky sound that presaged his Young Americans album. (And it’s here I should pause to praise Chris O’Leary’s books Rebel Rebel and Ashes to Ashes, which, combined, offer an exhaustive, song-by-song look at Bowie’s career. Both are fact-filled and thoughtfully written. Essential stuff.)

1975’s Cracked Actor, directed by Alan Yentob, is pretty fascinating in a few ways. We get a British television doc’s perspective on Bowie but we also get a look at the condescending attitude of the American press in the opening footage. Pennebaker’s film offers a little of the circus swirling around Bowie in the early ’70s, but there’s more of that here. Even more interesting are the scenes of Bowie at work, including shots of him using the technique of cutting up phrases and letting where they fell help shape his lyrics, an approach borrowed from Burroughs and artist Brion Gysin. One of the discarded ideas from around this time was a Ziggy Stardust musical in which the scenes would change from performance to performance based on chance.

Most memorably, though, is the look it offers at Bowie in L.A. Later in life he often brought a sense of playful self-mythologizing to tales of his drug excesses but here he truly appears to be a man at the end of his tether. This is the coke-and-milk phase of his life referred to above, but also a period in which he’d immerse himself in occult literature and documentaries about Nazis and books trying to make connections between the occult and Nazis. This kind of stuff was floating around the darker tinged post-hippie counterculture, and Bowie seemingly absorbed it enthusiastically. Bowie talked about hating L.A. but also fed off that hate. There’s a scary edge to him here, onscreen and off. Some of the most memorable scenes in Pennebaker’s film are the ones that make a divide between on-stage Bowie and off-stage Bowie, but Yentob’s film moves in the other direction, depicting a Bowie where the lines between reality and artifice have gotten blurry. Cracked Actor isn’t everything you might want a look at this phase of Bowie’s career to be, but I still think it’s pretty compelling. What did you think?

Scott: I think it’s a fascinating documentary about a confusing and difficult time in Bowie’s life, and I credit Yentob for getting the most of his time doing interviews backstage or in limos. He might open with that interview with the condescending American journalist—and what an absolute knob that guy is—but you can tell that Bowie feels comfortable going deeper into himself than you might expect from any star, much less one who can hide behind the personae he’s created. As for Bowie’s psychological state at the time, the key moment for me in Cracked Actor is this reflection on fame:

“Do you know that feeling in the car when someone is accelerating very, very fast and you’re not driving? And you get that ‘oof’ thing in your chest when you’re being forced backwards and you’re not sure whether you like it or not? That kind of feeling is what success was like. The first thrust of being totally unknown to being what seemed to be very quickly known was very frightening for me.”

We think about Bowie as this larger-than-life figure, but he had to have been surprised by his music breaking big into popular culture because there wasn’t a template for it. It must have felt accidental and more than a little surreal. Spending time in Hollywood certainly doesn’t seem like the best way to ground yourself, and I couldn’t help but think about The Man Who Fell to Earth (which we’ll discuss at length in time) when Bowie is getting driven around in a limo, a stranger in a strange land. His feelings of disconnection and dissociation are heightened by his relationship to his own stage creations: At one point, he talks about how he’s not sure if he was writing characters or they were writing him or there was no difference between these possibilities.

Once again, however, the performance footage leaves something to be desired. I marvel again at how dynamic Moonage Daydream feels because some of the raw material is just that, raw. But wow does that Diamond Dogs tour look incredible anyway. Between the additional resources that fame brought him and the creative peaks of that period, Bowie must have put on some electrifying shows.

Before we close out this conversation on Bowie the musician, however, we wanted to take a quick look at some highlights of his music videos– which, in some cases, seemed far ahead of the times in understanding where videos were going. What do you think?

Keith: If we think of our current moment as being not that different than 2016 when it comes to music videos, Bowie’s career pretty much spanned the whole history of the form. I’m sure my first encounter with Bowie was in the early ’80s when “China Girl” and “Let’s Dance” were unavoidable on MTV. I like that era of Bowie a lot, but it’s also, as Moonage Daydream touches on, a moment in which he consciously remade himself to fit the spirit of the moment rather than letting pop culture rearrange itself around his latest incarnation. Not that Bowie didn’t soak up influences and change his direction throughout his career thanks to his interest in soul, disco, electronic music and so on, but that was the moment when he decided to make himself approachable to MTV kids and the moms and dads who bought records for them until eventually all there was left to do but make a Pepsi commercial with Tina Turner, sing underneath a big spider, and try to start all over again by forming a band with Soupy Sales’s kids.

We don’t have space to look at all (or even most) of Bowie’s videos, but there’s a neat throughline to them if you just follow the progress of “Major Tom,” the alienated astronaut first introduced in Bowie’s 1969 single “Space Oddity.”

“Space Oddity” was born of a video project that never saw full release until years after Bowie became famous. Love You till Tuesday was an attempt to showcase the then-struggling artist and “Space Oddity,” recorded in January of 1969, was the last-moment addition that some of those around Bowie dismissed as a crass novelty song designed to cash-in on the upcoming moon landing. It failed at that, but it ended up becoming his first U.K. hit in September, months after Neil Armstrong and company had returned safely from the moon, their minds and bodies intact, unlike poor Major Tom. But should we pity him? Maybe he touched the transcendent and moved onto the next phase. 2001: A Space Odyssey was Bowie’s other reference point.

There are several “Space Oddity” videos. The best known, featured above, was directed by frequent Bowie photographer Mick Rock when the song was re-released in America in 1972. It finds him looking a lot more like Ziggy than the space-and-folk inspired Bowie of 1969 you can see in the original video:

The 1972 version features the better known (and better) version of the song, but I love the original video here, which features a nascent Bowie still figuring out how he plays on camera in the middle of a low-budget and quite literal recreation of the song. It’s charming.

By 1980, both Bowie’s screen presence and music videos had evolved:

“Ashes to Ashes” is a song from the other end of a decade that had seen Bowie rocket to fame and deposited him on the other side a little worse for wear. (See above, re: milk and cocaine.) Lyrically, it revisits the fate of Major Tom with a little less ambiguity, as the singer hopes to avoid that fate himself by “staying clean tonight.” Or maybe that’s the wish of a man in a padded cell or floating in space or otherwise unable to come down to earth.

Directed by David Mallet, the “Ashes to Ashes” clip takes the music video form seriously at a time when others weren’t, when videos didn’t yet have a fixed place on television as they would after the coming of MTV. Bowie and Mallett seem quite aware of the form’s potential, however, from the blown-out imagery made possible by new technology to the suggestive imagery that could enhance a song’s impact rather than undermine it by, say, making the star dress up like an astronaut. Instead, put him a clown costume on a beach with a bulldozer and let others figure it out.

“Space Oddity” and “Ashes to Ashes” provide bookends to the first decade (give or take a year) of Bowie’s career, but it’s not the end of Major Tom. But before we get to the second half of the story, what are your thoughts on these?

Scott: My introduction to Bowie was surely through the music videos first, specifically “Let’s Dance,” which I’d have seen as an 11- or 12-year-old who listened to popular radio, but tended to gravitate towards songs that had a little art in ‘em. (When I was even younger, I annoyed my parents by constantly borrowing Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band from our next-door neighbors, who they detested. I was the weird kid who loved– and still love– “Within You Without You,” but that’s a conversation for another time.) But really, Keith, no mention of Bowie and Mick Jagger’s “Dancing in the Street”? What an embarrassing oversight!

It should have come as no surprise, in retrospect, for Bowie to have been on the vanguard of music videos, since his recordings do not fully capture the multi-dimensional experience of Bowie as a creator of characters and conceptual artist. I’m with you in preferring the original “Space Oddity” video to the Mick Rock-directed one, though I can see how the latter reinforced the Ziggy Stardust image and featured Bowie looking more fully formed as an artist. “Charming” is the right word to describe Bowie’s presence in the original video, and I think the partial dramatization of the song works in its favor, because it effectively evokes the magisterial loneliness of “sitting in a tin can, far above the world.” (I also like that the astronaut costume is emblazoned with “MAJOR TOM” in big letters, just like a real space mission.)

“Ashes to Ashes” is so forward-thinking, as you say, with a cool solarized color look and all those picture-within-picture transitions, which were exceedingly expensive at the time. I’m not sure what to make of Bowie walking around in a distressed Pierrot costume or the frequent cutaways to an unvarnished Bowie sitting in a padded room, but music videos don’t really need to make a lot of sense. Particularly funny to me in this video is that it’s completely abstract right up until the end, when it literalizes the line “My momma says/to get things done/ you’d better not mess with Major Tom” by having Bowie stroll along the beach with an elderly woman we take to be his mom.

To jump ahead in Bowie videography, the 1995 video for “Hallo Spaceboy (Pet Shop Boys Mix)” is worth a second look:

I think if you’re looking anywhere for an example of what Brett Morgen is trying to pull off with Moonage Daydream, this video is as good a place to start as any. It’s not about telling a story, however obliquely, but about achieving a visceral, associative experience through montage. The cuts come fast and furious between footage of Bowie performing by himself in a stylized space, the Pet Shop Boys singing in close-up, and clips of vintage science-fiction films that add up to a panic surrounding an alien invasion– and that’s still just a partial description of the images that are thrown into the mix. The song is fast-paced and energetic, in keeping with the spirit of Outside, the record it was promoting, which led naturally to a tour and collaboration with Nine Inch Nails. That’s another thing about Bowie: He was always plugged-in to the music of the day and could uncannily find himself in it.

Finally, you suggested we look at Bowie’s video for “Blackstar,” which I’d never seen and which moved me deeply:

The video runs nearly 10 minutes, and ends the “Major Tom” cycle with the suggestive image of a skeleton inside a spacesuit. Bowie knew he was dying of liver cancer when he recorded Blackstar the album, and it’s simply one of the greatest swan songs I can recall from any artist. It’s not often that a filmmaker or musician gets a chance to be that conscious of the end, but Bowie planned for it and the video is so haunting and beautiful. Morgen turns to it extensively for Moonage Daydream, even though the song isn’t featured in the film, which to me indicates Bowie’s talent for self-mythologization. He was following through a story that he’d spent a career telling.

What did you think, Keith? What’s the standout Bowie video for you?

Keith: With all respect to David Mallet — who also directed the “Hallo Spaceboy” video and a bunch of other Bowie clips (including the “Dancing in the Street” duet) — “Blackstar” is some kind of masterpiece. Specifically the video, though I feel the same way about the song and the album of the same name. The song’s lyric opens it up to any number of readings but as soon as you settle on one it falls apart. The video doesn’t settle anything; it only raises more questions. Who are these characters Bowie is playing? Where is this taking place, really? What is this all about?

Major Tom isn’t in the song but he’s central to the video — or what remains of him (which is now a bejeweled skull). Is this an acknowledgment of Bowie’s own impending death?

Directed by Johan Renck from ideas and visuals provided by Bowie, there’s nothing in the video to tell you, and it would break with Bowie tradition if there was. And, like you, I find it incredibly moving. Even if it’s not a self-conscious goodbye — he made more videos after this, including the even more explicitly death-focused “Lazarus,” also directed by Renck, and was making plans for another album and more projects to the end — it’s the work of an artist continuing to experiment and push further even in the face of death. It’s a goodbye note as magnum opus, one that, as he’d done throughout his career, powerfully combines music and images that could exist without each other but take on new layers of meaning together.

We could go on (and on and on) apparently. But let’s save some Bowie movie talk for next week when we look at Bowie at the movies via two of the most acclaimed films in which he appeared: The Man Who Fell to Earth and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.

I've never gotten over Blackstar and the way it feels like Bowie orchestrated his own death. Somehow he remained artistically vital and never stopped pushing himself into new places even as his end was coming - I remember reading about how arduous the Lazarus shoot was because of how little energy he had. To have those efforts culminate in such a masterpiece of an album and two videos that seem to prepare us for the death that would come just days after the album's release... It's awe-inspiring and heartbreaking.

I despair at the thought of what might have come next while being grateful that he got to put this one last beautiful statement into the world. He could have chosen to spend those final days in private and make his death a personal matter, but instead he put on a new character to find a way to help us cope with his passing as well.

I don't know if this *really* counts as Bowie-as-musician, but it's still one of my favorite things ever: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jv6mEv_rDdE