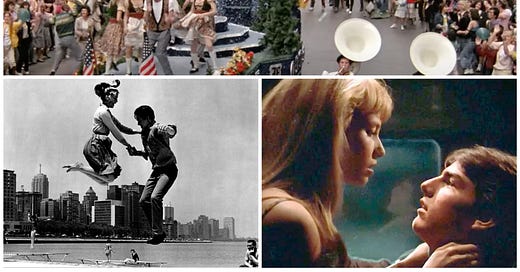

Lately I’ve been thinking about the United Artists Theatre and all the movies I’ll never see there. You can see its marquee—a multistory fixture with giant letters that stretched around the corner of Dearborn and Randolph where it once stood—in the background of The Blues Brothers, Adventures in Babysitting, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. It was in the lattermost film where I first saw it. It’s deep in the background of the Von Steuben Day parade scene and not in the frame for long but you can’t miss it. I spotted it while watching the movie at an Ohio mall multiplex, then looked for it whenever I rewatched the film at home. Never mind Matthew Broderick lip-syncing surrounded by cute dancers: What is that? And what’s it showing?* Little did I know then that the United Artists Theatre wasn’t long for this world. By the time I got here, it would be long gone.

The United Artists began as the Apollo Theatre in 1921, a live theater space that began showing movies in 1927. The marquee arrived sometime in the 1950s and stood until the theater’s demolition in 1989, a blank slate advertising nothing for over a year after the venue closed in 1988. Despite being born in the Midwest, I didn’t make it to Chicago until 1996 and didn’t really get to know the city until moving here in 2001. (In some ways I still think of myself as a new arrival, compared to those who’ve lived here all their lives.) From the start, I got the feeling that, for all I’d get to experience here I’d missed a lot.

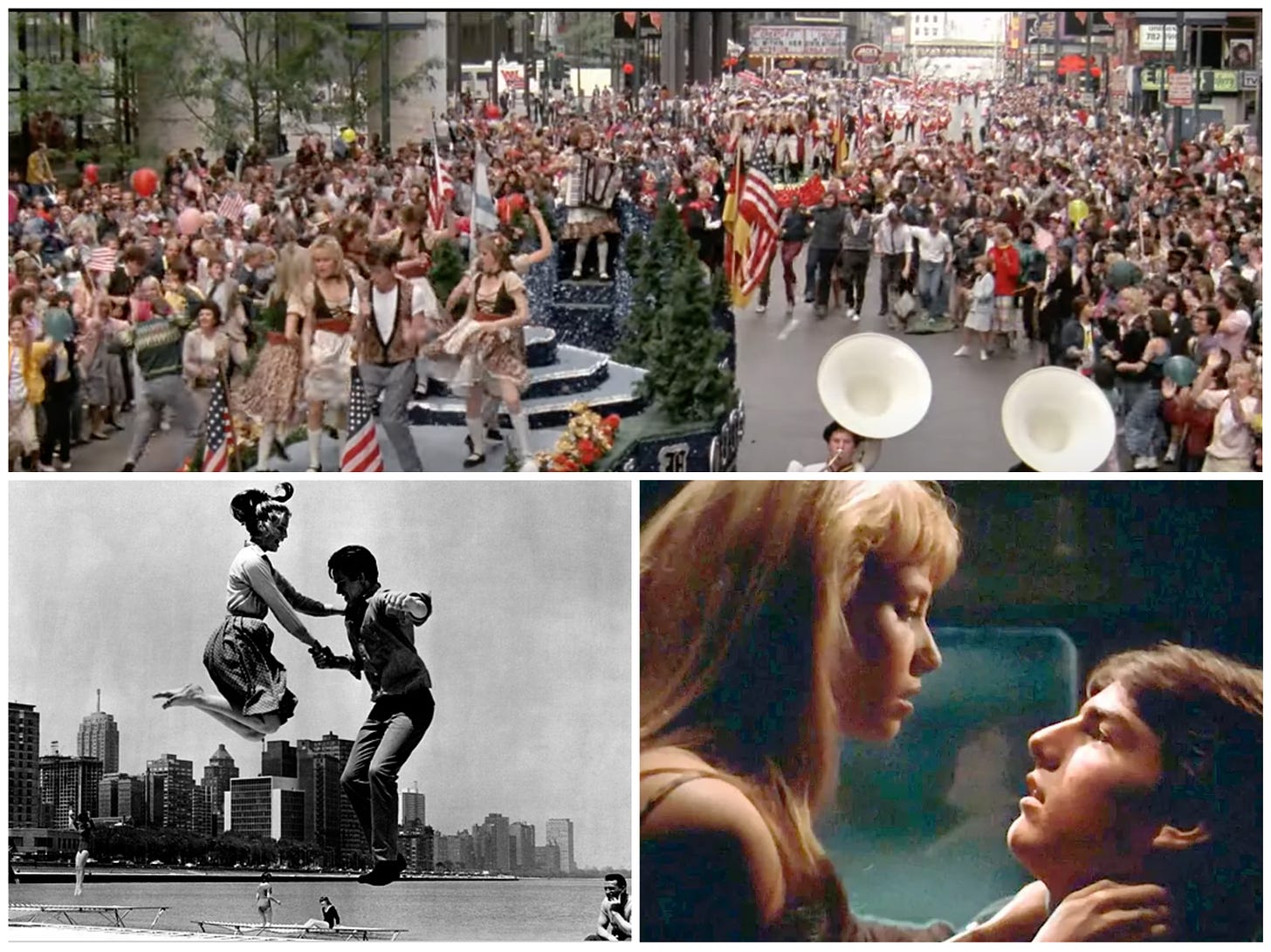

The late Chicago film critic Sergio Mims used to speak longingly of the ’70s, when a moviegoer could go from a Loop theater playing blaxploitation movies to another showing kung-fu films, cycling through one stop after another and never seeing the same movie twice. The United Artists Theatre, like the other long-demolished downtown theaters with glamorous beginnings, grindhouse declines, and inglorious ends, is part of a Chicago I’ll never get to know.

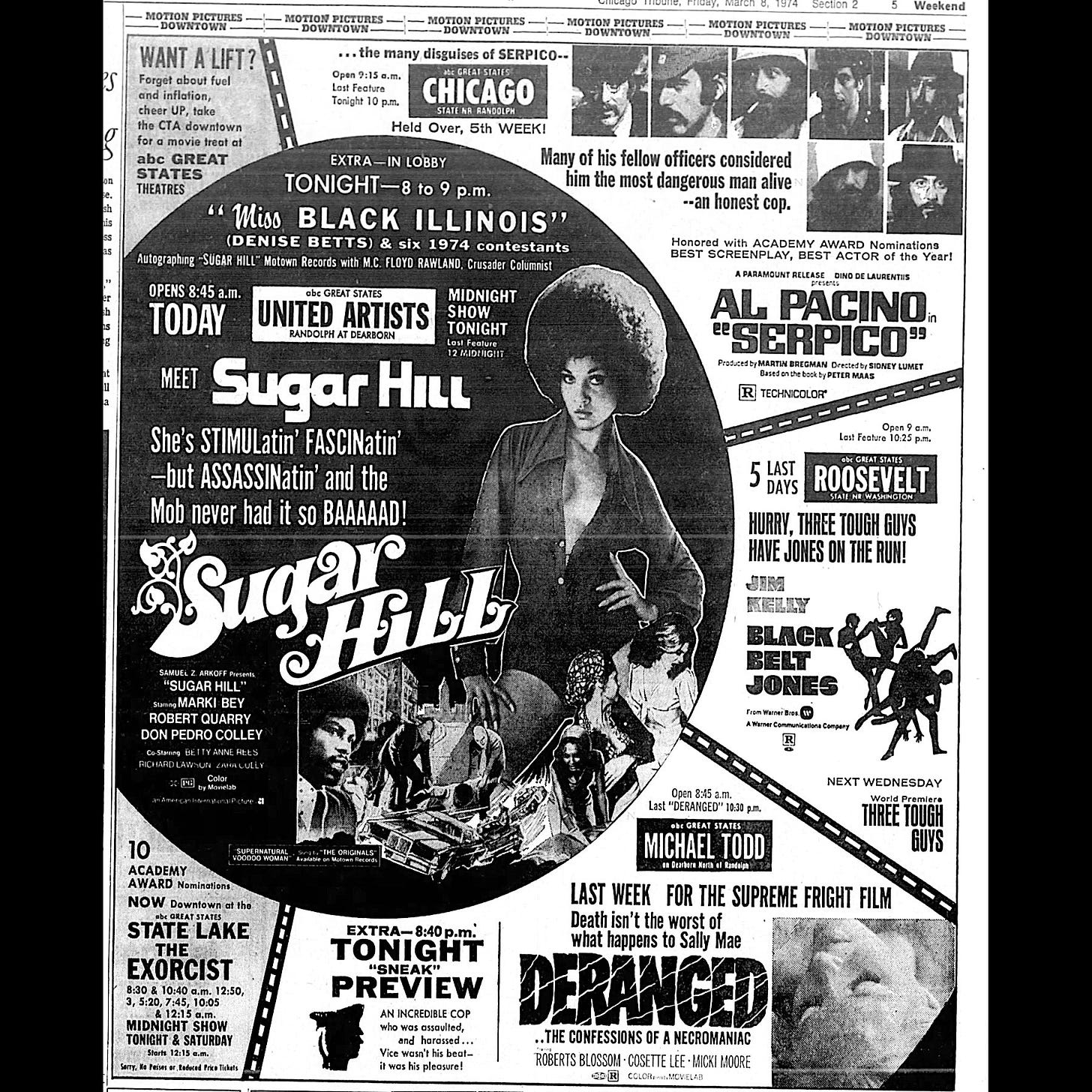

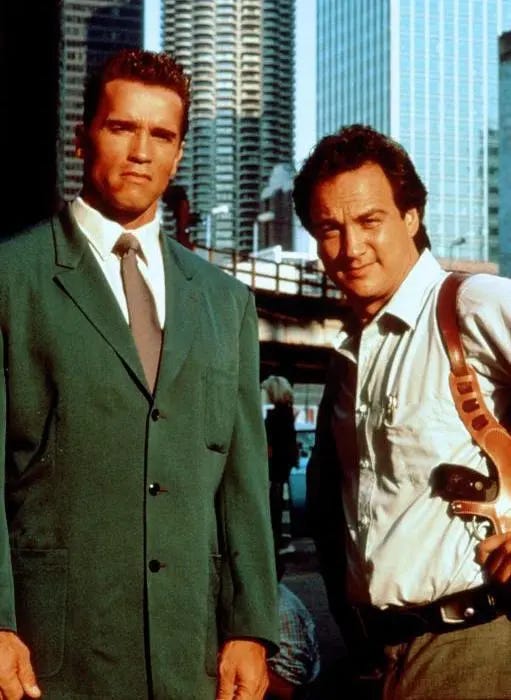

It’s a weird kind of nostalgia, or some emotion akin to nostalgia, to be in a place and yearn for it at the same time. Maybe that’s why movies filmed in Chicago before my time have a special fascination to me. I recognize the places I see but I don’t know them. Time has dramatically altered the grungy, neon-drenched, crime-ridden Wicker Park seen in Red Heat, for instance, unrecognizable now but for the unmistakable Flatiron Building. Even the places that haven’t changed take on a kind of exoticism. The beachfront path Amy Irving and Melody Scott Thomas walk in The Fury hasn’t really changed, but the trash cans and phone booths, to say nothing of the fashion on display, mark it as belonging to another era. (Look quickly and you’ll see that Jim Belushi is in both of the clips linked above.)

Some Chicago spots have become inseparable from their movie appearances. Visit the Art Institute and you’ll see an overwhelming collection of masterworks, including Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. It’s an unforgettable work, but I can’t separate it from Cameron’s dark reverie in (once again) Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. I pass the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge in Uptown all the time. It’s a great, intimate place to hear some music and its striking exterior has remained the same since well before I was born. But there’s a weird disconnect to seeing it standing intact after watching it explode in Thief. Walk by the Chicago Board of Trade and it’s hard not to at least consider the possibility that a clash between Batman and the Joker might break out.

You can time travel to virtually any past Chicago since the invention of film, but some more easily than others, since the city has gone in and out of vogue as a filming location over the years (a cycle sometimes influenced by what tax incentives are being offered at any given time). The first movie shot in Chicago (or at least the oldest known to history) dates (probably) to 1896 and was shot by Alexandre Promio, an employee of Auguste and Louis Lumière. (You can’t get much closer to the source than that.) Running just 48 seconds, “Chicago Police Parade” features just what it promises. Another Lumiere production from 1896 shows the first-ever Ferris wheel, built for the 1893 World’s Fair, slowwwwly making a rotation.

I used to live near one of the most important sites in Chicago film history, Essanay Studios, or what remains of it. An elaborate door with the word “Essanay” above it still stands on the grounds of St. Augustine College where Essanay Studios once operated. Essanay produced movies featuring Gloria Swanson, Wallace Beery, and many others, including Charlie Chaplin. It was a busy place, home to everything from the (probable) first pie-in-the-face gag to the first Sherlock Holmes movies. But, as anyone from Chicago will tell you (at length), the weather here can be lousy. Chaplin shot only one short, “His New Job,” in Chicago before moving to Essanay’s California facilities. It was undoubtedly a great place for studio work, but exteriors were another story.

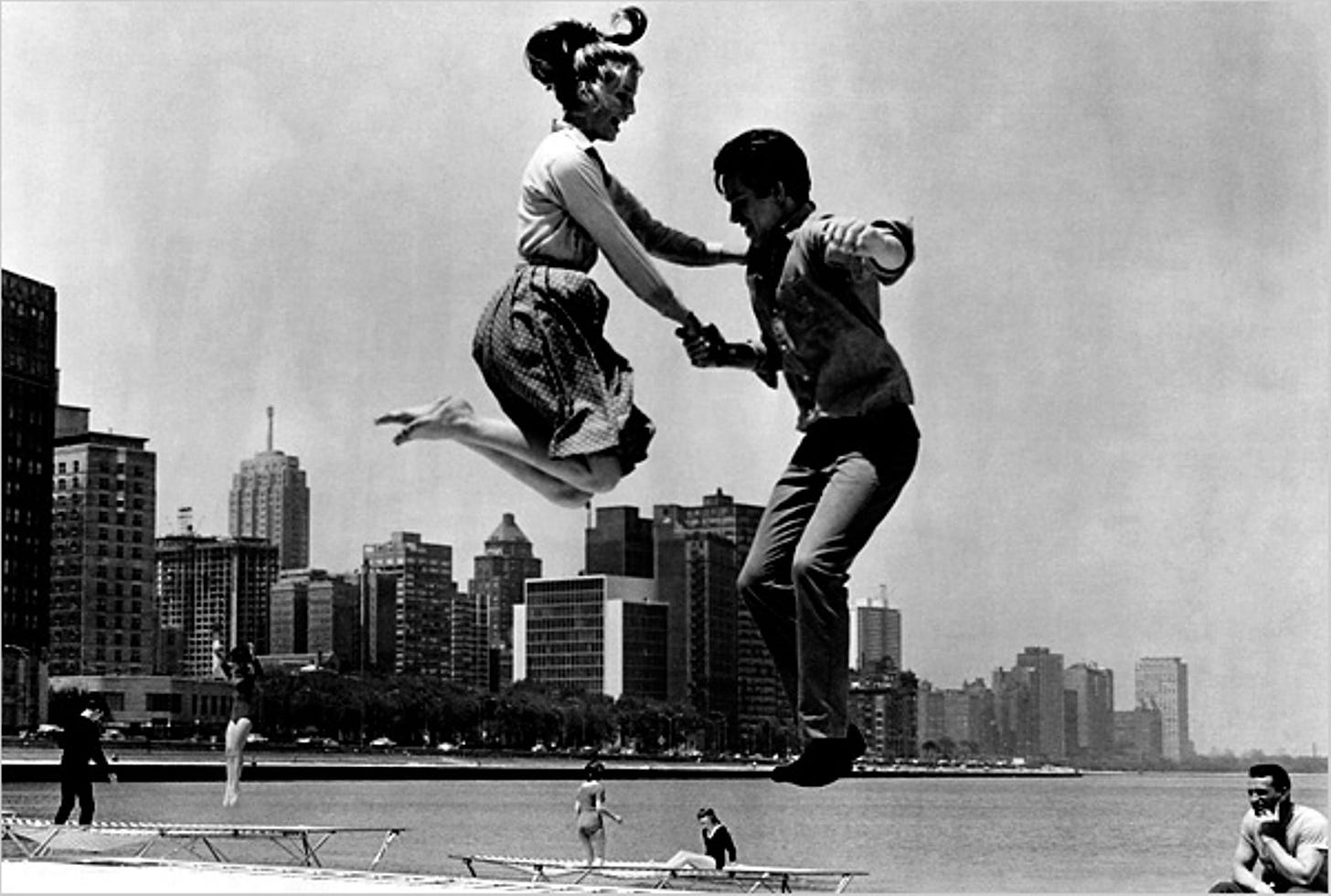

Movies filmed in Chicago thinned out during Hollywood’s golden age, as the center of filmmaking gravity shifted west and on location filming became a rarity, but occasionally filmmakers would remember the Second City had its uses, and things started to pick up in the 1960s. The home from A Raisin in the Sun still stands, for instance, as does the exterior at least of the Kitty Kat Club, a South Side gay bar that also served as a filming location. One of the pleasures of Arthur Penn’s Mickey One is that it seems to come from an alternate universe, one in which the French New Wave took place not next to the Seine but on the banks of the Chicago River. About halfway through, Penn drops in a shot of Warren Beatty and Alexandra Stewart jumping on a trampoline in slow motion on the shore of Lake Michigan before cutting to a shot of the couple in bed. (It’s a symbol, see.) I like the movie as it is, but I can’t help but wish for more such shots.

I guess mostly I’d love to be there on that sunny day and see that Chicago. Or dine in the classic steakhouse Lee Marvin visits in Prime Cut. Or ride the El as seen in Risky Business with Tangerine Dream playing on a brand new Walkman. (I’d exit and let Tom Cruise and Rebecca DeMornay have their privacy, however.) The places remain but the moment moves on.

Maybe it’s less nostalgia than disbelief. There’s a bit of egotism to this feeling. Seeing shots of the Chicago that used to be is a bit like seeing pictures of a romantic partner before you met them. Logically, of course they had a life before you. But in some respects that seems impossible. Didn’t their story begin when it joined yours?

Maybe I’m overthinking this. Maybe I’m just romanticizing that Chicago because it’s unreachable. Reality will never interfere with my idea of what it would be like. There’s an obvious dark side to this way of thinking. When I recently posted about the United Artist Theatre on Bluesky, I received a reply with a link to an image and the joking (I assume) words “This exact photo of the city is suddenly my RETVRN,” a reference to the alt-right word for a desire to return to an older, better time. I don’t want to return (or retVrn) to that past. But I can’t help but feeling like I would have loved some aspects of it.

A shopping complex called Block Thirty Seven now stands on the lot where the United Artists and two other old movie palaces once stood. It has an AMC multiplex on one of the upper floors. My family and I saw The Boy and the Heron there. I loved the movie but couldn’t tell you a thing about where I saw it. I think there might be a grilled cheese place on the first floor.

The Instagram account Windy City Ballyhoo, which features a remarkable collection of images from Chicago’s moviegoing past, deserves a tip of the hat for helping inspire this piece. It’s also on the site now called, sigh, X.

* Freeze the frame and squint and it appears to be the 1985 film Creator starring Peter O’Toole, Mariel Hemingway and Virginia Madsen.

Me feel same way about old New York movies, which obviously there no shortage of. (Fun City Cinema podcast was terrific excuse to revisit different eras of city).

But then, me also like present-day New York movies so me can do Leo-pointing-at-TV when me see places me have been to. Nick and Nora's Infinite Playlist will always have soft spot in heart because A) they get NYC geography right (Hoboken, not so much), and B) it closest anyone has come to capturing nights out me had as young monster decade earlier.

Great piece, Keith.

Just want to add "Medium Cool" and its extensive shots of the city, especially Uptown.

I also love the extended shots of the car lots that use to line Western Ave in "Thief."

Oh, and finally: "My Bodyguard," which has great Chi scenes and is kind of a lost treasure.