Anniversaries: Steven Soderbergh’s 'Solaris' at 20

The director's adaptation of a classic science fiction novel helped cool a hot streak. It deserved a better fate.

Near the end of First Man, Damian Chazelle’s 2018 film about the Apollo 11 moon landing, Neil Armstrong (Ryan Gosling) stands alone on the surface of the moon. His lander behind him and his companion, Buzz Aldrin (Corey Stoll), otherwise occupied, Armstrong drops the bracelet of his daughter Karen, who died of cancer at the age of two, into a crater, watching as darkness swallows it. It’s a lovely moment that uses visual shorthand to express what its taciturn hero knows but would never say out loud: no matter how far you go, even if you go further than anyone has ever gone before, you can never really leave anything behind.

Any similarity between Chazelle’s film and Solaris in any form — be it Polish science fiction writer Stanislaw Lem’s original 1961 novel, Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film, or Steven Soderbergh’s 2002 adaptation — doesn’t extend much further than using the vastness of space as a stage for an expression of personal loss. But each version in its own way captures the same collapse between what’s grand and cosmic and what’s internal and personal — inner space and outer space, in other words — that makes Armstrong’s moment at the crater's edge so powerful.

I’m an admirer of both Lem’s novel and Tarkovsky’s film, but both have been securely canonized and don’t really need anyone else to make a case for them. Soderbergh’s version, on the other hand, has struggled for respect for 20 years. That’s always puzzled me but probably shouldn’t. Here was Steven Soderbergh riding the hottest of hot streaks on the heels of Erin Brockovich, Traffic, and Ocean’s Eleven (and, sure, a star-filled little blip of an indie film called Full Frontal that, admittedly, nobody saw but seems like it wasn’t made with any illusions that anyone would) making a science fiction movie for a major studio starring George Clooney, a star similarly at the height of his commercial powers.

The only problem: instead of a warp-speed adventures with a man-of-action hero, Soderbergh delivered an opaque, contemplative psychological drama about Chris Kelvin (Clooney), a therapist whose trip to the far-away planet of Solaris forces him to reckon, once again, with the guilt and regret that have haunted him since his wife’s suicide. Perhaps sensing an unwinnable situation, Twentieth Century Fox crafted a shrug of a trailer that framed it as an odds-defying love story and played up the involvement of producer James Cameron with a credit reading “From the Creator of Titanic.” (Thomas Andrews would like a word.) Also possibly contributing to a sense of bait-and-switch: a lot of pre-release publicity about Soderbergh and Twentieth Century Fox appealing the MPAA’s original R-rating, applied to the film because of shots of Clooney’s bare backside. (My favorite headline from the era is from ABC News: “Big Stink Over Clooney’s Butt.”) CinemaScore, the market research firm that polls filmgoers with audience reaction surveys, reported it earned a rare “F” rating.*

It’s not a film that asks viewers to love it. It’s icy on the surface, but that’s a cover for the roiling emotions beneath, much like the confident expression Clooney uses to hide the pain and vulnerability Chris feels inside. He’s a man used to the pain and vulnerability of others. (It’s Clooney’s most frequently deployed trick as an actor, but it’s a good one.) The film’s opening moments include a brief scene of Chris leading a group therapy session for those traumatized by some unspecified tragedy, one that’s dominated news footage and inspired memorials across the world. (The year in which the film takes place remains unspecified, but the 9/11 resonance is hard to mistake.) He seems to be good at his job but he ends the day alone. It’s his choice. As he’ll later explain, he’s found it easier, given what he’s been through, than being with someone else.

Chris’s solitude is interrupted, however, by a pre-recorded message from space, specifically from an old friend named Gibarian (Ulrich Tukur), a scientist living in a station orbiting the mysterious planet called Solaris, where something has gone wrong. What, specifically, remains unclear even after Gibarian’s message concludes. What is clear is that they want Chris’s help but currently can’t see themselves coming back to Earth. “The most obvious solution would be to leave,” Gibarian tells Chris. “But none of us want to.”

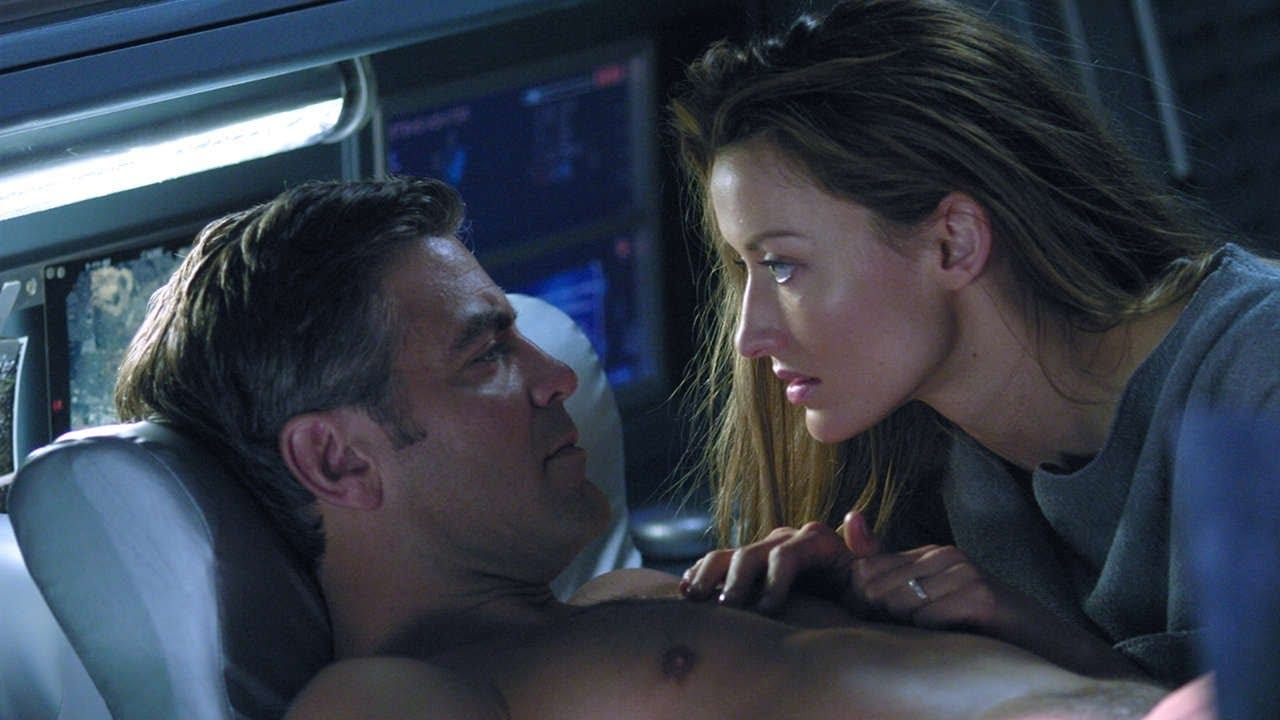

Upon arrival at the station, Chris starts to understand. He finds Gibarian has died by his own hand, but the crew members left behind — Snow (Jeremy Davies, delivering the most Jeremy Davies performance of his career) and Gordon (Viola Davis) — share their commander's mixed feelings about leaving. They also talk of “visitors” and, once Chris goes to sleep, he gets a visitor of his own in the form of Rheya (Natasha McElhone), his late wife, whose memories of their life together are both pleasant and vague—and absent any details of how it ended.

What follows, for all the talk of Higgs particles and such, is a marital drama in sci-fi trappings set in a place where feelings of guilt and hope coexist in a confusing swirl. One remarkable sequence recalls the love scene from Out of Sight, an homage to Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now that cuts between shots of lovemaking and the flirtation that precedes it. Always unafraid of bold editing strategies (though a few narrative leaps in the film suggest a little too much tightening), Solaris one-ups his previous effort, erasing years of time and (presumably) light years of space by alternately showing Chris and Rheya making love on Earth early in their relationship and the couple doing the same on the station.

Only now one half is a ghost or an illusion or something science could probably explain but hasn’t quite found a way to yet. Soderbergh flits between the relationship’s beginning to a point well past when it should have ended, by all known laws of time and space. But maybe, the construction of the moment suggests, nothing really ends. Maybe the ways the past bleeds into the present — as we recall happy moments, wince at old missteps, and feel the years fall away at the jolt of an unexpected memory — is not really an illusion at all.

Soderbergh’s film is lockstep tonally with Cliff Martinez’s score, which bounces swelling strings against pulsing percussion provided by steel drums and xylophones in ways that suggest strong emotions but refrain from specifying just how those in the audience should feel about what they’re experiencing.** The situation of Chris and the others caught in Solaris’ orbit at times doubles as a metaphor for depression, but it’s never just that. In a 2003 interview Soderbergh said he saw the planet Solaris “as a very convenient and wonderful metaphor for anything that you don't understand.” The Solarian visitors are terrifying and seductive, but perhaps mean no harm as they tap into the deepest feelings of those they encounter and force them to revisit and reconsider the most important moments in their lives, with all the attendant feelings of joy and pain.

That ambiguity continues through the final scene, a cosmic grace note more open to interpretation than a Rorschach blot, one that recalls (and possibly refutes) Chris’s earlier mockery of the very idea of God or perhaps leaves him trapped in an illusion of his own making. Maybe that irresoluteness and the possibilities it suggests are why audiences revolted. Maybe that’s why the film’s admirers, however few, love it. It’s a gaze out into the bewildering cosmos made from the most modest of perspective: a single soul coming to accept there’s no escaping the past that defines him.

* That makes it one of now still only 21 films to earn that rating, a club that now includes The Box, In the Cut, and mother! Scott has long argued that a pretty great film festival could be put together from CinemaScore Fs and I can’t disagree.

** I used to write to the soundtrack album quite a bit. I’m not sure which I’ve heard more: this or Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’s score for The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford.

Right. I love Soderbergh but he definitely keeps some key collaborators in his shadow. I'd love to hear from them and Roderick Jaynes while we're at it.

20 years on and it's so weird that Peter Andrews (the DP) and Mary Ann Bernard (the editor) still won't give interviews without Soderbergh being there.