Agnieszka Holland Goes to War

On the connections between the Polish director's controversial new migrant drama 'Green Border' and the historical forces at play in her 1990 breakthrough film 'Europa Europa.'

With her immensely powerful and provocative new movie Green Border, opening this week in limited release from Kino, the Polish director Agnieszka Holland takes on the sort of migrant crisis that’s stoked conflicts among neighbors around the globe, as families fleeing war, extreme poverty, climate change, or some combination of the three are scrambling to resettle in countries that are often hostile to them. Every situation is different, of course, depending on the scope of the crisis and the politics surrounding the immigration issue, which broadly seem to be stoking nationalism and moving governments to the right. But the one common thread, immediately apparent in Green Border, is that refugees are left twisting in the wind, considered at best a problem to be solved and at worst less than fully human. The Polish guards in Holland’s film refer to them sarcastically as “tourists,” just passing through the country before they are deposited across the razor wire into Belarus. Or tossed.

Though Holland has been active in film and television since the mid-‘70s—she was an assistant director on Andrzej Wajda’s 1983 masterpiece Danton, and worked with other major Polish figures like Krzysztof Zanussi and Krzysztof Kieslowski—she didn’t find international recognition until Europa Europa, her justly acclaimed 1990 film about Solomon Perel, a Jew who fled Nazi Germany as a 13-year-old after Kristallnacht and wound up surviving the war by masquerading as a Nazi and even becoming immersed in Hitler Youth. Though separated by over 30 years, Green Border and Europa Europa reveal a remarkable consistency of thinking on Holland’s part, particularly the way she aligns herself with characters who are rendered homeless, displaced by wars they had no hand in waging and treated as hassles or “tourists” or much, much worse.

Despite her roots in Poland, which were complicated even before Green Border sparked a massive political firestorm, Holland herself has been a woman without a country—or, to put it in more positive terms, a citizen of the world. She emigrated to France in 1981 after the Polish government cracked down on strikers and demonstrators with the formation of a military junta and a period of martial law that lasted a little under two years. She made the Oscar-nominated 1985 film Angry Harvest, with Armin Mueller-Stahl, in Germany and found French and American financing for the 1988 English-language film To Kill a Priest, a fact-based drama about the murder of a Polish priest under the direction of the communist government. (Christopher Lambert, Ed Harris, Tim Roth, Pete Postlethwaite, and Timothy Spall are among the loaded cast for that one.)

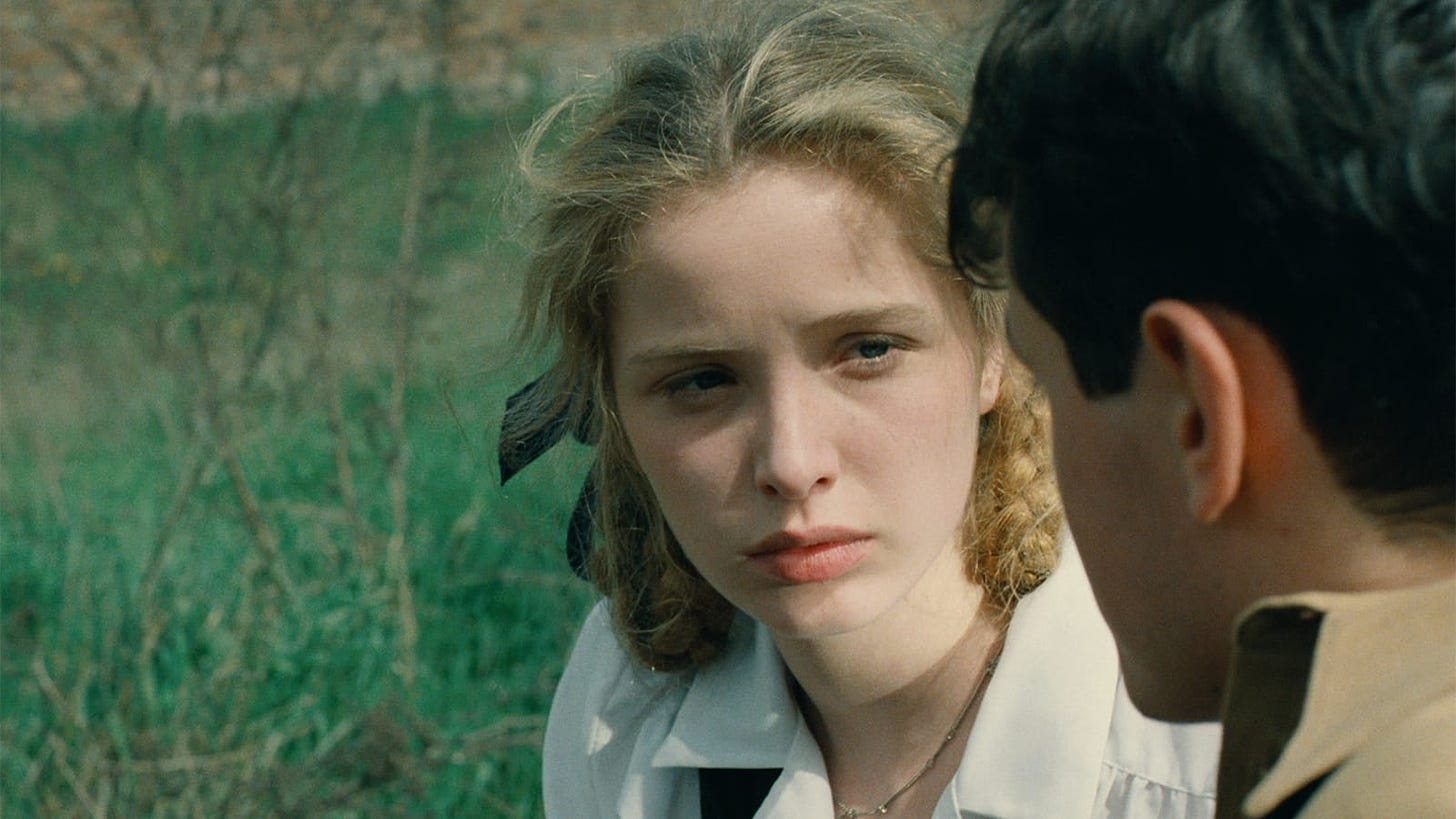

While Europa Europa led to the superb (but now very hard to see) French film Olivier Olivier, with young Grégoire Colin, and a hugely successful Hollywood debut with her 1993 adaptation of The Secret Garden, Holland never quite found her footing in America, whiffing badly on the 1995 erotic drama Total Eclipse, with Leonardo DiCaprio and David Thewlis, and not getting much traction from her 1997 period romance Washington Square, with Jennifer Jason Leigh, despite mostly friendly reviews. Throughout the ‘00s, Holland shifted into a few gigs directing stellar TV shows, including a few episodes each of David Simon’s series The Wire and Treme, and prestige hits like The Killing and House of Cards. She never entirely stopped making films, but Green Border has gotten more attention in critical circles than anything she’s done since Europa Europa and it’s worth noting how little Holland’s focus has changed in the three decades-plus between them. If anything, she’s gotten feistier.

***

The one major element distinguishing Europa Europa from Green Border—and, in my view, making it the richer of the two films, if not as viscerally effective—is how much irony and dark humor figures into Solomon “Solek” Perel’s odyssey through Nazi Germany, Poland, Russia, and back again. As a 13-year-old from a persecuted class, Solek survives by his wit and by a series of close calls that, taken together, are lucky to the point of seeming like a divine miracle. (The real Perel, who appears as himself in the film’s unforgettable epilogue, didn’t die until last year, at age 97.) And while posing as Nazi eventually confronts him with serious moral and identity crises, his fate rests heavily on the missing foreskin that becomes his most closely guarded secret. “No one believes me, but I remember my circumcision,” says Solek in the opening narration. Turns out to be no small snip for our hero.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Reveal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.