A Charming Chameleon with a Scorpion's Tail: On 'Color of Night'

Born of the erotic thriller boom of the early-'90s, Richard Rush's infamous flop is an unclassifiable oddity.

Early in Richard Rush’s 1994 film Color of Night, perhaps the most deliriously unhinged of the ‘90s erotic thrillers that flooded theaters and video stores after Basic Instinct, Dr. Bill Capa (Bruce Willis), a New York psychologist, gets into a heated argument with a patient. In the opening scene, we’ve already gotten an indication of this patient’s mental state—and the film’s color palette—as the patient paces around her bedroom in a silky green negligee, applies ruby-red lipstick like Diane Ladd in Wild at Heart, and puts a gun in her mouth. Her session with Capa ends with her turning away from him, dashing through his ornate office window, and falling many stories to the street below, shards of glass trailing her as she goes. When she lands, Rush and his cinematographer, Dietrich Lohmann, offer a shot from below the pavement as the blood pools out, as if the concrete were transparent.

Welcome to giallo, American style, brought to you by Hollywood Pictures, the Disney production label for live-action films considered too hot for Touchstone. (Though Color of Night would be by far as hot as Hollywood Pictures would get over its mostly ignominious 19-year run.) The definition of what films can be called giallo is fraught—our friend Noel Murray wrote about it when the term came up in connection to the giallo-adjacent Last Night in Soho and Malignant—and Color of Night is such an odd mishmash of tones or genres that it doesn’t fit into a single box. But many of the basic elements of work by Italian filmmakers like Dario Argento, Mario Bava and Lucio Fulci apply here: The byzantine mystery plotting, the “masked” killer, the florid sexploitation, and, of course, the searing primary colors, which are so integral to the film that they’re worked into the title and the psychosomatic color-blindness that afflicts its lead character.

This was not unknown territory for Rush, a cult filmmaker who managed to work on and off for decades, despite a bumpy career full of films that would only later find small pockets of appreciation. Even when his one widely acclaimed film, the gonzo 1980 moviemaking comedy The Stunt Man, earned him a Best Director nomination at the Oscars, so few saw it in theaters that its star, Peter O’Toole, quipped that “The film wasn’t released. It escaped.” The same might be said of other Rush orphans like 1970’s Getting Straight with Elliott Gould and Candice Bergen, which no less than Ingmar Bergman called “the best American film of the decade,” and 1974’s Freebie and the Bean, a hit with audiences that would only later find prominent appreciators in Stanley Kubrick and Quentin Tarantino.

One indisputable fact about Rush is that he was a student of the medium, having cut his teeth on Korean War propaganda films before excelling at American International Pictures, the independent outfit that specialized in drive-in fare, but happened to produce Roger Corman’s Poe movies and imported Bava’s Black Sunday in 1960. Among Rush’s AIP movies was 1968’s lively Psych-Out, a drugged-out time-capsule movie that counts Susan Strasberg, Jack Nicholson, Dean Stockwell and Bruce Dern among its stars.

None of this is to establish Color of Night as a misunderstood masterpiece—it’s undeniably disjointed and wounded, if unworthy of the Razzie-sweeping ridicule heaped upon it—but there’s at least some tension between the highly charged, offbeat erotic thriller that Rush seemingly wanted to make and the Basic Instinct cash-in that the studio and his producer, Andrew Vajna, expected of him. Nobody involved ended up happy, as Rush and Vajna fought over the final cut and the film tanked with critics and audiences. But Color of Night has a quality to it. It is not a mediocrity by any stretch, much less the sort of deliberate mediocrity that risk-averse studios put out in abundance.

For Vajna, Color of Night was a chance to counter (or maybe just rip off) his old producing partner Mario Kassar, who had made a cultural sensation out of Basic Instinct, expertly stoking the controversy that had swirled around it. The two had founded Carolco Pictures, which left a huge imprint on American action films of the ’80s with the Rambo trilogy and Total Recall before Vajna left to start his own company, Cinergi Productions. (Carolco’s future was a wild ride, with blockbusters like Terminator 2, Basic Instinct, Cliffhanger, and Stargate somehow not enough to eke out a profit before the $147 million loser Cutthroat Island finally tanked it in 1995.) In the two years since Basic Instinct, theaters and video stores had become flush with imitators, like Body of Evidence (featuring Madonna, Willem Dafoe, and candle wax) and Dream Lover (featuring James Spader and Mädchen Amick), and VHS counterparts like Body of Influence and Indecent Behavior, the latter starring Shannon Tweed, who carved out her own sexy thriller niche.

The template for Basic Instinct is apparent in Color of Night, particularly in the casting of Bruce Willis as Capa. Capa may be a shrink, but his tough-guy attitude, wedded to Willis’ Die Hard persona, squares with the cop-on-the-edge played by Michael Douglas. Though Capa is a psychoanalyst tormented by his failure to save a patient, Willis plays him as a man of action, as skilled at improvising his way through car chases and knife fights as he is operating a group therapy session.

In the Sharon Stone role of a sexy, mysterious lust object who may or may not be a serial killer, model-turned-actress Jane March was about as marginally known as Stone was before Basic Instinct, having caught only a little attention for her blazing turn in Jean-Jacques Annaud’s The Lover two years earlier. Both films owe their tough-guy/femme fatale dynamic to film noir, but Douglas and Willis were modern action stars, obliging them to deliver acrobatic setpieces inside and outside the bedroom.

And yet, Rush won’t be constricted by any boundaries. In the immediate aftermath of the suicide—“That was the reddest blood I ever saw, pooled around her green dress,” says Capa, before losing his ability to see colors—the action shifts to a Monday group therapy session in Los Angeles and the tone shifts in kind. Dominic Frontiere’s score turns jaunty as Rush introduces us to Dr. Bob Moore (Scott Bakula) and five patients with seemingly nothing in common: Sondra (Lesley Ann Warren), a nymphomaniac in an appropriate red-and-green dress; Clark (Brad Dourif), an accountant with OCD who likes to count books on the shelf (foreshadowing alert!); Casey (Kevin J. O’Conner), a glib painter with an interest in sadomasochism; Buck (Lance Hendricksen), a gruff former cop who lost his wife and daughter in an incident he refuses to describe; and Richie, a transgender teenager with a drug problem.

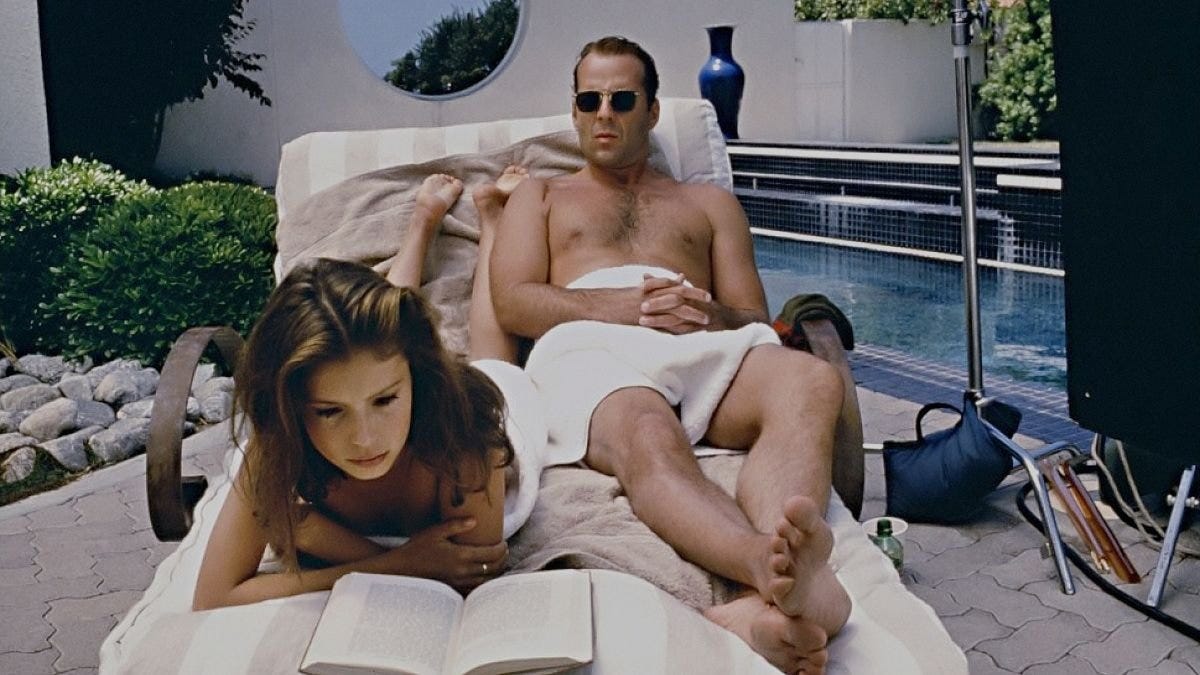

Dr. Moore is an old friend of Capa’s, and he’s invited him to crash indefinitely at his home, which Moore has designed like a high-tech fortress to protect himself from someone who has been threatening him, likely a client. No matter. Moore is stabbed to death in his home anyway, leaving Capa to settle his affairs. With encouragement from an overzealous police detective (Rubén Blades, having the time of his life), Capa continues to work with Moore’s Monday group in a long-shot effort to snuff out the killer. Meanwhile, an exotic beauty named Rose (March) meet-cutes Capa by crashing into the back of his car (“Ms. Fender Bender,” she calls herself) and, yadda yadda yadda, they’re making waves in the pool a full year before Elizabeth Berkley and Kyle MacLachlan had their infamous splish-splash in Showgirls.

It’s difficult to know how to react to Color of Night, because it’s so many things at once: an outrageously twisty thriller and whodunit with action beats, a hot-and-heavy sexploitation film for date night, a comedy about the wackadoos at group therapy. Strike that. It was not that difficult for many to react by finding it ridiculous and laughing at it, which is understandable. Here’s a film in which a rattlesnake springs out of a mailbox like a fake nut can and Brad Dourif mumbles bitterly about a lover’s annoying proliferation of cotton balls.

Then again, one of the few critics to defend Color of Night at the time, The New Yorker’s Terrence Rafferty, straight-up calls it “a comic murder mystery” in the opening sentence before going on to compare the film to Beat the Devil, John Huston’s confounding camp classic from 1953, which few (including its star, Humphrey Bogart) liked at the time. Rafferty seemed to write his review for posterity, knowing that a bomb was incoming.

That said, the argument that Rush’s follow-up to The Stunt Man, his first film in the 14 years, was teasing the audience in the same rascally, self-aware way doesn’t always hold water, despite the ever-present reminder that the director of Color of Night isn’t some anonymous studio hack. There are plenty of elements that we’re meant to take seriously that are plain silly, most of them rooted in a script that plows gracelessly into the gender dysphoria of Psycho and the more unsavory aspects of Dressed to Kill and Sleepaway Camp. Rush stakes way too much of the film’s impact on a twist that surely everyone in the audience can see coming from reels away, and a word like “facile” doesn’t even begin to describe its psychological insights.

And yet, again, it has a quality to it. Rush’s go-for-broke visual bravado is something to behold—not since Persona has a film been so thoroughly enamored by reflections—and March is a transfixing presence, despite the received wisdom that Color of Night was a career-killer for her. (It’s complicated.) Willis mostly glowers through his performance, but he doesn’t need to do much to get sparks from March, who has an alien beauty that couldn’t be further removed from Sharon Stone’s cheerfully vulgar update on the Hitchcock blonde. She’s asked to do a lot more than the sex scenes—which, to my mind, are among the steamiest of the era—but at the risk of spoiling this easily spoiled film, I’ll say that she’s range-y yet vulnerable, part femme fatale and part tragedienne. Ms. Fender Bender is revved up for trouble.

I love this movie and Rush’s entire bananas filmography. Among friends, I will admit to being an unreconstructed Freebie and the Bean fanatic, even though I can’t imagine a movie more out of step with contemporary mores, right down to the ugly racial slur that’s conspicuously half of the damn thing’s title.

“psychosomatic color-blindness that afflicts its lead character.”

This is the most prominent of several things that make me feel like this was supposed to be a De Palma movie.

As someone who was in his late teens when all of these Basic Instinct imitators were released, I remember each and every one quite well. This one was easily the most interesting. Of course, I wasn’t thinking of directors at all at the time, would not see Stunt Man for many years yet. Now I want to go back and re-watch this; I really enjoy all of the other Rush films I’ve seen, as it turns out.