1991: A Summer at the Movies, the Best Job I Ever Had, and What Came After

Some reflections on working at a movie theater 30 years ago, things left behind, things lost, and hours spent watching films like 'V.I. Warshawski'

It was early on a Sunday morning when I unexpectedly got a call from Omar asking me to come into work. The movie theater had been broken into overnight. There was glass everywhere and he needed someone to keep watch while he took care of a few things and talked to the police. When I got there, I found that, if anything, Omar had been underselling the scale of the damage. Whoever had broken in had destroyed one of the thick glass windows in the entryway, presumably using some kind of makeshift battering ram. Fortunately, they didn’t seem to have any interest beyond the candy counter. “It must have been kids,” Omar surmised. The unspoken question: What kind of muscled-up kids could do this? Across the lobby, posters featuring the heroic faces of Daniel Day-Lewis and Kevin Costner offered no answers, just as they’d offered no protection the night before. It was the summer of ’91, and troubled times had come to the Loews Salem Avenue cinema.

But only briefly. The Great Candy Heist would be the height of the theater’s drama that summer, at least as I experienced it. John Hodgman once compared working at a movie theater to being to becoming part of a family. For me, joining the staff in the months between graduating high school and shipping off to college — if going to a school just a couple of zip codes away can be called shipping off — felt a bit like signing on as a recurring character in someone else’s long-running show. All the key plot threads and interpersonal dynamics predated my arrival and would last beyond my departure, and I mostly only observed them from a distance.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

I was accepted into the fold but never became a full participant in the main storyline, whose most exciting episodes had, I heard, involved boozy after-hours screening parties and illicit dalliances in the projection booth. That was fine by me. I liked my co-workers but some were best appreciated at arm’s length, like David, whose blaring car alarm went off if the wind blew the wrong way and matter-of-factly talked about the semi-automatic rifle he kept in the trunk. David looked like the kind of long-haired metal guy who scared me in high school, but at the movie theater we got along just fine.

Fewer and fewer were visiting by the early ’90s, when the pull of the multiplexes with screens in the double digits had made it increasingly difficult to attract moviegoers to a three-screen theater that most people now just drove by, no matter how massive its parking lot or how alluring I found its fading grandeur. Old-fashioned prejudice also played a role in its decline. Getting to the theater involved crossing a semipermeable cultural divide from the almost entirely white suburb in which I lived to the mostly Black neighborhood just south of the falling-out-of-fashion shopping mall that served as a weekend destination for my family through much of my childhood. For many of those who lived around me and in similarly homogenous suburbs on the north side of Dayton making that crossing just wasn’t done.

Their loss, of course. I’m not sure what made Omar decide to bring me on for the summer. I was a lumbering white kid who talked too much about movies even for someone who wanted to work at a theater. It probably helped that Matt and Sharon, recently graduated classmates who worked at the theater, vouched for me, but it was ultimately only Omar’s decision. The Loews Salem Avenue was his domain. A big man with a piercing glare, Omar treated the theater as if he owned it. Some people exude authority given the right surroundings and Omar was one of them. He talked, you listened, and you restocked the Junior Mints to his liking or you’d hear about it. Not that he’d yell. He commanded the respect of a drill sergeant without raising his voice. He was also one of the funniest people I’ve ever met. When I told him that I suspected my older cousin might have taught him in high school and then told him my cousin’s name he replied, “That explains a lot.” No further comment. I’m glad he hired and mostly tolerated me.

I applied for the job almost on a whim, but the theater had been an important place to me for a long time. It’s where I saw a movie as a child (either Snow White or You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, my memory is fuzzy). Back then it was called the Kon-Tiki, named for the raft manned by Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl on a 1947 voyage from Peru to the South Pacific in an attempt to prove the people of Polynesian journeyed there from South America. (Heyerdahl survived the voyage. His theory has not.) The reference made a lot more sense when the theater opened in 1968, just in time to catch the tail end of American interest in all things Polynesian or, more accurately, “Polynesian.” Culturally sensitive or not, the Kon-Tiki was still a garish wonder to behold. When Loews purchased it in the mid-‘80s, the chain stripped it of its magnificent if deeply tacky tiki heads but, the sloping entryway roof — meant to recall a South Pacific hut — and the shell-shaped sinks remained.

Despite the declining attendance, in the ‘90s it remained an amazing place to see a movie, even if it sometimes seemed to specialize in the ones no one wanted to see. Loews Salem Ave played some blockbusters, sure. In the summer of ’91 it ran Terminator 2 and… that might have been it. At one point we showed both Mobsters (hot young stars play old time-y gangsters) and Body Parts (Jeff Fahey gets an arm transplant and things go murderously awry) to less-than-packed houses. I didn’t join the staff in time for the release of the John Stamos-starring Born to Ride — log line: “The US Army recruits a delinquent biker to train their new motorcycle squad for an important mission” — but I was there for the entirety of Drop Dead Fred’s run. Those who did show up for screenings, especially those in the main house, enjoyed some neglected splendor thanks to a huge screen and an expansive auditorium that included a balcony. A balcony! How many operating movie theaters had one of those in 1991? It almost made up for the disappeared heads.

Despite Omar’s exacting expectations, the job was, frankly, pretty easy. I mostly worked the concession stand, which meant, on a good day, tending to a rush of customers every couple of hours then a lot of standing around and goofing off, maybe even occasionally playing a round of Shinobi, one of the arcade games located in the lower lobby near the rarely used second concession stand. To feel as if we were doing something, we’d check in on the theaters once in a while, ostensibly to confirm they were at the right temperature but really to make sure none of the patrons were up to no good. That was rarely a problem. I once had a disgruntled customer throw popcorn at me — or in my general direction at least — but nothing worse than that.

When not restocking the candy counter my main responsibility was to clean up after the movies ended, a job that began when the closing credits started to roll as no one then had reason to stick around for post-credits Easter eggs. That meant I saw the endings of our longer-running films many times, especially Terminator 2 and the gutting final moments of Jungle Fever. Sometimes I’d show up early to make sure I caught the whole confrontation between Samuel L. Jackson, Ruby Dee, and Ossie Davis. That a pretty great Stevie Wonder song plays over the soundtrack provided a reason to slow-walk the clean-up.

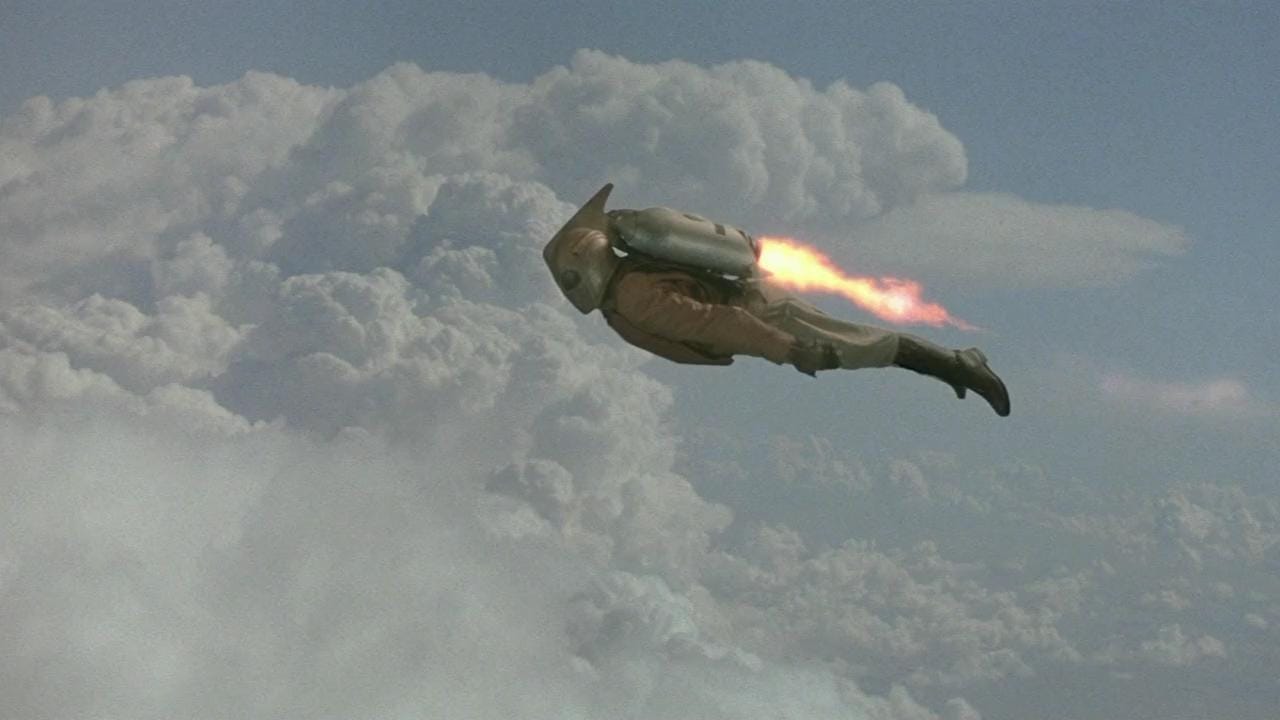

Lunch breaks provided even more opportunities to catch at least part of a movie. I think I saw The Rocketeer only once in full but many times in bits and pieces. Once, when we weren’t as busy as anticipated, Omar asked me to clock off early to save the theater some money. That, in retrospect, wasn’t entirely fair, but Omar must have sensed, rightly, that this was just a pocket money job for me. No hard feelings. I stuck around and watched a movie for free. (True, it was just V.I. Warshawski, but whatever.)

Besides, there were fringe benefits. Employees could show up and get waved into movies for free anytime we liked. Movie theaters, understandably, serve as magnets for people who like movies. At Loews Salem Avenue that included Andy, who was studying film at a nearby college and dating my friend Sharon. I thought I knew plenty, but Andy made it clear how much I still had to learn, especially about the outré outskirts to which I’d already started to gravitate. Sure, I’d seen Peter Jackson’s Dead/Alive, but had I seen Bad Taste or Meet the Feebles? Those were hard to find in America, but Andy knew a guy who could hook me up. What about Frankenhooker? No, ignore the title, he insisted, it was actually pretty good! (I still haven’t seen Frankenhooker. Someday I should find out if he was right.)

Sharon was my age, Andy was a few years older, and it appeared as if they’d eased into something like an adult relationship, the first time I’d witnessed such a thing with someone I knew. At least that’s how it looked from the distance at which I remained. Andy and I didn’t talk about personal stuff all that much, but we did talk about movies, the ones he loved, the ones I loved, and the one he was in the process of making for a film class.

I only really knew Andy for the few short months we worked together and the few weeks I rejoined the staff during a long winter break from college. We did stay in touch for a bit in that labor-intensive pre-internet way. He sent me a letter at school updating me on theater goings-on and included some movie recommendations, including one for an insane-sounding erotic drama starring Nicolas Cage called Zandalee. Before long the correspondence tapered off.

I don’t remember my last shift that summer. I mostly remember the end of the summer as a long process of everything falling away as all my friends left town for school on a staggered schedule. One day, say, Bryce or Mark or Kim were around. The next they’d moved on. Maybe, as I waited to make my own departure, they already had a sense of how profound a change leaving for college would be. But that’s not the sort of experience you can easily convey to those who haven’t yet shared it.

I left, too, but I didn’t entirely cut ties with my co-workers. Omar and a handful of the others visited me that fall when Spike Lee spoke at the college I attended about 45 minutes away from my hometown. I invited them up to my dorm room and showed them around. I loved seeing them and had no idea then that our worlds wouldn’t overlap like this again. When I was 18 it was harder to understand that when things end they end.

The last time I saw Omar he was sweeping up at another Loews theater where I’d taken my parents to see Little Women. A few years had passed. We said hello and chatted briefly, but he seemed busy. He wasn’t wearing a manager's uniform. He was dressed like an ordinary employee. It looked all wrong. I think about him from time to time, but my attempts to find out what happened to him have been fruitless.

I bumped into Andy by chance sometime in the late-’90s. I can’t remember exactly when, but I’d stopped by some kind of fall street festival in Ohio where he was working, I believe, at the merch table for a local cable access station. He and a few other horror movie enthusiasts had helped launch a kind of comeback for Dr. Creep, a local TV host from our childhood, even reviving the name of his old show: Shock Theater. Andy looked different — tired and distant, stripped of the enthusiasm I knew. “I finally made a movie,” he told me. Our conversation didn’t get much further than that.

I should have made an effort to stay in touch. I could say it was harder in those pre-social media days, but that’s probably just an excuse. I did Google him from time to time and was happy to discover he did keep making movies even though I never sought them out. With all respect to Andy’s talent as a filmmaker, they sound like the sort of underground horror movies I respect in theory but try to avoid, exercises in extreme content and discomfort with names like The Mutilation Man. I learned later they came from a place of real pain, which you can read about in the biographical essay Andy wrote about his career in 2006. It's filled with details of a disturbing childhood we never talked about at the time. I only discovered that piece when, after not checking in on his career for a few years, I learned that Andy had taken his own life in 2013. He was 40.

The theater closed in 1999. It lay vacant for six years before being demolished. I recently found a newspaper clipping about locals getting a chance to take one last look inside before the wrecking crew went to work. In the accompanying photos, the sinks still looked like seashells. Candy thieves couldn’t break the Loews Salem Avenue, but time, indifference, and cultural divides could. Now when I drive by, my mind can’t quite square the vacant lot with what used to be there. It still feels present but it’s long gone.

(This essay changes the names of the living.)

Never worked in a theater, but I rue and lament the closing of the Bedford Theater here in Nova Scotia. It was opened until about 2006 or 2007, and it was my favourite theater to go to (for all the reasons that led to it being closed...the decor was old and tired, it was rarely busy, but it was also the most convenient location for me to get to and from by bus). We also had the one screen Oxford Theater here near downtown Halifax that was a genuine old style movie house, with one screen, an old style box office, and a balcony! The last movie I saw there was Brooklyn with Saoirse Ronan, and it wasn't long after that that it closed down. I saw a lot of good movies there (Schindler's List, The Big Lebowski, Apocalypse Now Redux), but when all the theater chains got gobbled up by Cineplex, there was no more room for a one screen theater that favoured Oscar Bait and other, smaller films.

This is a great piece, Keith. Thanks.