1950: The Year We Went to the Moon (Sort Of)

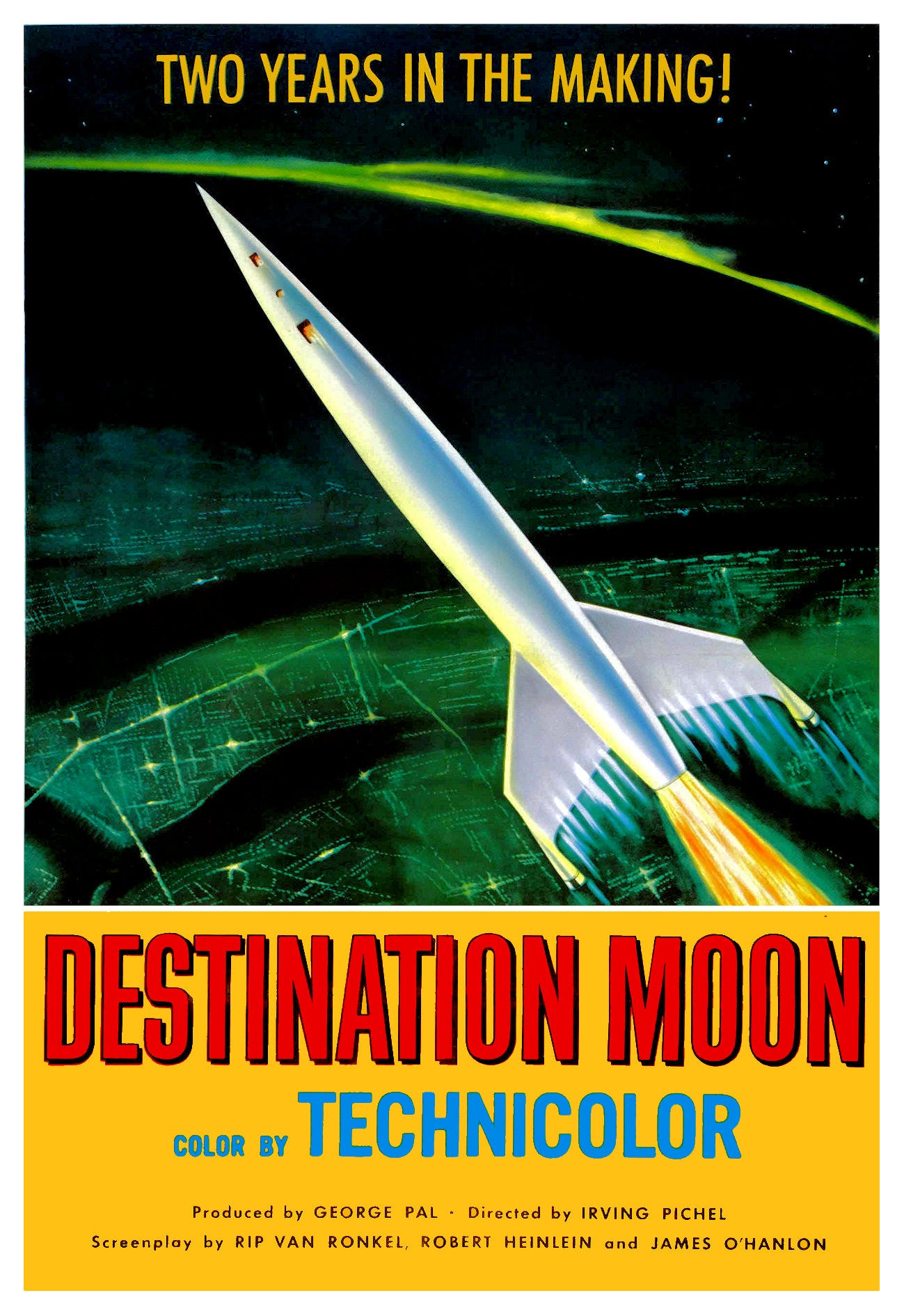

Released mere weeks apart 19 years before the moon landing, ‘Destination Moon’ and ‘Rocketship X-M’ competed at the box office while offering two sharply contrasting visions of space travel.

It’s not easy to fake a moon landing, as everything from conspiracy theory debunkers to the new comedy Fly Me to the Moon have demonstrated. You have to be convincing while depicting a place that no one in the audience has ever been—barring a surviving Apollo astronaut or two. You have to convey the moon’s reduced gravity without violating the laws of physics. You have to make it look otherworldly but not too otherworldly. The moon is, after all, essentially a big rock in the sky. And, given that last fact, you have to suggest there’s a reason to go to the moon in the first place by turning a big rock in the sky into a place of wonder. It’s a big ask.

Films had depicted the surface of the moon with varying degrees of seriousness prior to the midpoint of the 20th century, with Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Moon on one end of the spectrum and Georges Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon at the other. But 1950 serves as a clear watershed moment for moon movies, no doubt in part because advances in technology—both in the fields of science and filmmaking—made it seem like a goal that could finally be achieved. When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the lunar surface with a plaque declaring “We came in peace for all mankind” 19 years later, their success fulfilled a desire that had existed for as long as humanity had looked at the moon in wonder. But it also, on a much smaller scale, realized a dream set in motion by a different sort of moon race between a pair of films released in the first half of 1950: Rocketship X-M, which arrived in theaters in May, and Destination Moon, which followed in June and played alongside its predecessor.

The second came first. Rocketship X-M beat Destination Moon to the market but would not exist were it not for the canniness/shamelessness of budget-minded producer and theater owner Robert Lippert who, after catching word of a movie about the first voyage to the moon being made, rushed his own take on the subject into production. This, as Bradley Schauer recounts in his book Escape Velocity: American Science Fiction Film, 1950-1982, did not sit well with Eagle-Lion, the independent production studio behind Destination Moon, prompting the company to issue a press release with the header “A Slight Case of Mistaken Identity.” “Destination Moon,” it claimed, “was the first picture to be made on the exciting subject of planetary exploration.” It was the Armageddon-versus-Deep Impact of its day.*

Eagle-Lion’s frustration is understandable. The company had spent over a year developing Destination Moon and boasted of the film’s special effects and scientific accuracy. The brainchild of George Pal, it marked the Hungarian producer and Puppetoons creator’s transition from animation to science fiction and fantasy filmmaking.** To realize his vision, Pal turned to screenwriters Rip Van Ronkel and James O’Hanlon before bringing in Robert Heinlein, by 1950 already one of the few science fiction writers to find a wider audience, thanks to stories in mainstream periodicals like The Saturday Evening Post and Boys’ Life.

The credits describe Destination Moon as having been adapted from a novel by Heinlein, when in truth it borrows elements from a couple of Heinlein stories. But the film’s emphasis on scientific detail, distrust of government institutions, and Cold War-inspired military pragmatism reveal Heinlein’s influence. “The rocket is an absolute necessity,” one character recalls another saying, “If any other power gets one out into space before we do, we'll no longer be the United States. We’ll be the Disunited World.” Both men are part of a privately financed operation that has to rush their rocket into space before the government can shut them down. (Think SpaceX but with a slightly less right-wing leadership.)

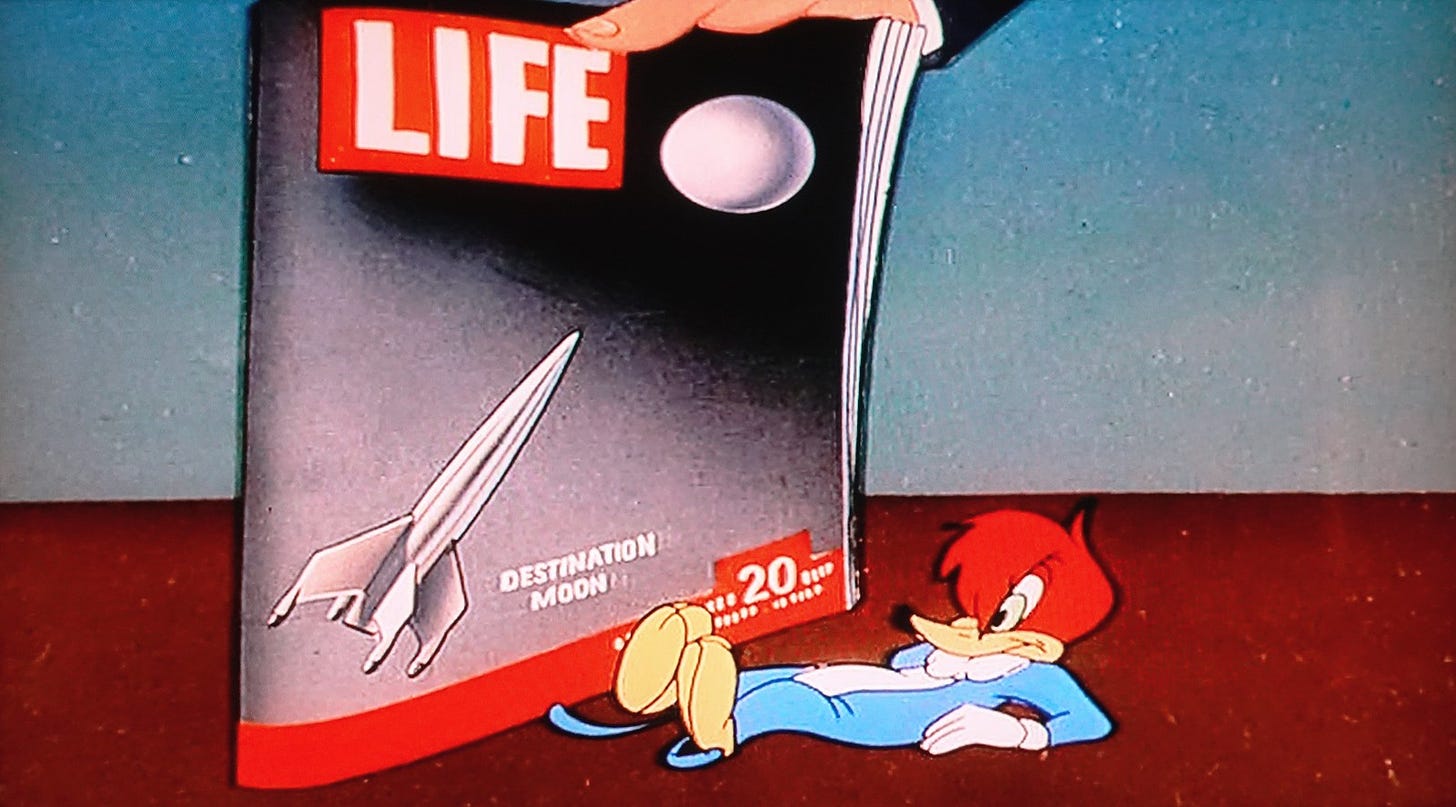

But before Destination Moon can send its crew into space, the film has to explain the science behind the voyage via a guest appearance from Woody Woodpecker. Created by Pal’s friend Walter Lantz, Woody shows up in an instructional video designed to persuade investors to put money in the project by asking the questions any layman (or laybird) would likely ask. Questions like, “How can a rocket fly without a propeller?” and “What do they use for fuel?” (Woody’s a bit like Jurassic Park’s Mr. DNA, only a dunce who has to be told everything rather than a know-it-all who does the explaining.) Once the voyage begins, Woody’s role is assumed by Joe Sweeney (Dick Wesson), a baseball- and goil-lovin’ harmonica-playing Brooklyn everyman who’s roped into the crew after one member develops appendicitis, perhaps realizing the film needs a touch of comic relief.

Joe’s one of the few nods to movie storytelling convention. Destination Moon’s style sometimes gets described as “semi-documentary,” which is a bit of an overstatement, but both the story and prolific director Irving Pichel’s filmmaking put the emphasis on the nuts and bolts of lunar travel. Sometimes literally: Destination Moon’s late-film drama comes from a need to lighten the ship’s load to compensate for a fuel shortage, requiring every non-essential element to be disassembled and discarded. One dramatic moment finds a character asking whether some fixtures are welded or bolted, sighing in relief to learn it’s the latter before saying, “Give me a wrench.”

A big hit in its day, Destination Moon picked up an Academy Award for effects and inspired a hit song of the same name (memorably performed by Dinah Washington, among others). Yet it’s not that surprising it’s semi-forgotten today, especially when compared to other Pal productions like The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine. What made it remarkable in 1950—the somber approach, convincing science, and memorable effects that brought the dream of lunar travel to the masses—has been overtaken by the realities of history.

Destination Moon’s smart, high-gloss depiction of space travel makes it a better movie than Rocketship X-M, but also strips it of its competitors' cheesy appeal. Directed by Kurt Neumann (Dracula’s Daughter), Rocketship X-M begins like a cheaper-looking companion piece to Destination Moon. Unremarkable black-and-white photography takes the place of Technicolor and the zero gravity effects have a distinct wobble and only sometimes conceal the wires being used to achieve them. But somewhere on the way to the moon, the eponymous Rocketship X-M (short for “Expedition Moon”) and its Lloyd Bridges-captained team runs into a little trouble that, oops, sends them to Mars instead. There they wander a landscape that appears to be red-tinted footage of L.A.’s Bronson Canyon and encounter remnants of a civilization they quickly conclude destroyed itself via nuclear war. But not, it turns out, without leaving some violent caveman-like survivors behind.

Though a smaller-scale success, Rocketship X-M may be the more influential of the two movies, at least within Hollywood. The 1950s would soon be filled with low-budget science fiction films. At least some would be set on the moon, which would serve as the home of sexy cat-women, flimsy-looking moonbases, and, in a film shown at select downtown theaters, a nudist colony. But who can say, really, what role each played in fueling the collective dream of traveling to the moon? Did seeing it projected in larger-than-life images make the moon look within reach in ways it never had before? Maybe 1950’s set-bound moons stoked the desire to stop faking the moment humanity touched the moon and, at long last, make it real.

* Or, maybe more accurately, the Jurassic Park-versus-Carnosaur, Destination Moon having been rushed into production to capitalize on a bigger budget title much like Roger Corman’s 1993 killer dinosaur movie starring Diane Ladd, Jurassic Park star Laura Dern’s real-life mom. Nobody in the cast of Destination Moon and Rocketship X-M appears to have been related, however.

** Not counting The Great Rupert, a bizarre and entertaining Christmas film in which Jimmy Durante co-stars with a stop-motion squirrel.

As an engineer, I love DESTINATION MOON, but there's a point at the start that really bugs me.

A first attempt to launch a satellite fails (it's hinted that this was foreign sabotage but this is never followed up on) but it's decided that since they are certain that rocket was perfect and the launch SHOULD have worked, they don't actually need to prove this and can jump straight to the moon rocket. That's not how it works!

They also gloss over how the rocket is going to return to Earth, showing a graphic of the entire vehicle descending via a parachute. That would have had to be one gigantic parachute. But this is just nit picking.

There's a bit at the end I particularly love, when Earth tells them the rocket is still too heavy to return and a character says "You could be wrong, couldn't you?" only to be told "I could, but I don't think the computer could!".

One of these won an Oscar, the other is on Mystery Science Theatre 3000, which, in a way, might mean Rocketship X-M has now had a potentially wider audience.