10 Thoughts on Alfred Hitchcock's 'The Birds'

In 1963, Hitchcock followed the mammoth success of ‘Psycho’ with an elusive, unsettling film unlike anything else he’d ever make.

By the 1960s, Alfred Hitchcock had become the most famous movie director in the world. Via cameos, a much-watched television program, humorous trailers, and books and magazines bearing his name and image, he’d become a kind of brand name. Brands create expectations. For The Birds, his 1963 follow-up to the massive success of the 1960 thriller shocker Psycho, he embraced some while discarding others.

1. It’s not the film I thought it was.

It’s very possible this is just me, but I’d come to regard The Birds as one of the more minor of Alfred Hitchcock’s major movies. I had not seen it since college until rewatching it recently and I remembered it as an excellent film that nonetheless didn’t play to Hitchcock’s strengths. It’s more monster movie than suspense film. It offered little of the psychological complexity of Hitchcock’s other films. Tippi Hedren was no Kim Novak. Rod Taylor was no Cary Grant (well, that was fair). Wasn’t the opening kind of slow? Was there really any even subtext?

Boy did I get it wrong.

2. The opening credits sequence a mini-masterpiece onto itself.

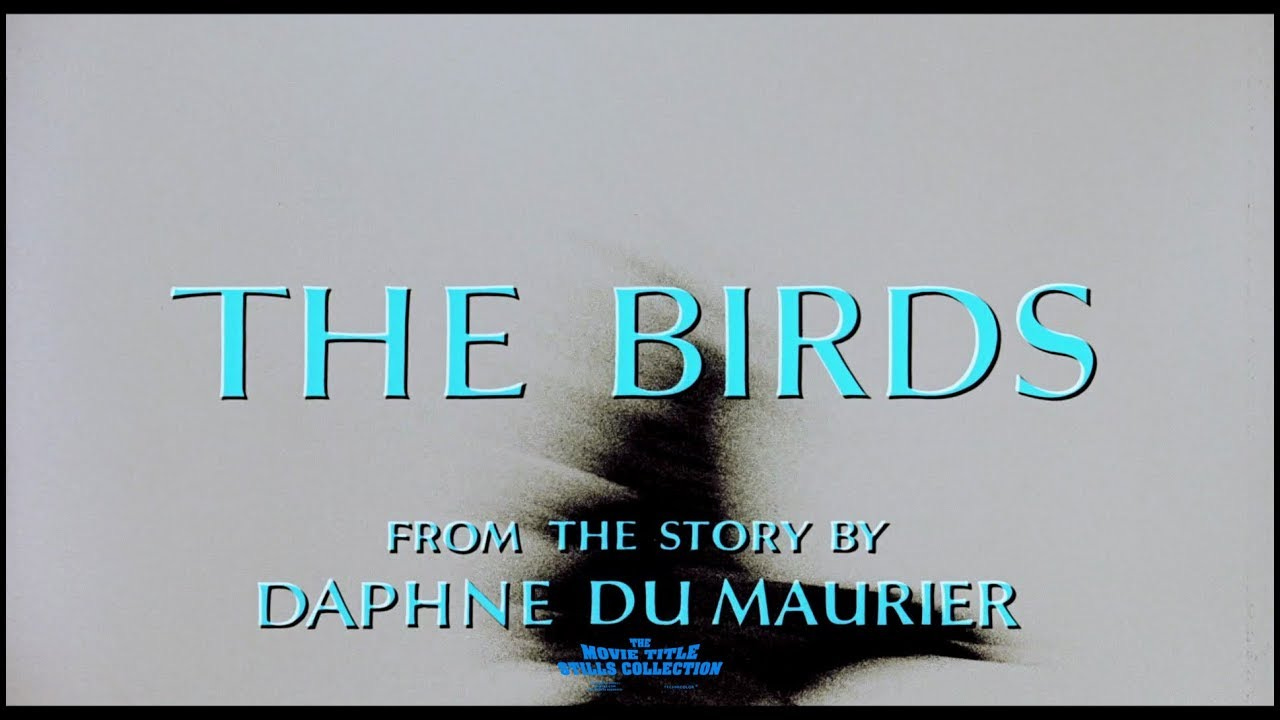

The silhouettes of birds flap frantically across a soft gray backdrop, accompanied by the sound of flapping wings, chirps and caws. I’m not sure how this was created. It appears to be images of real birds, but their movements are almost entirely on a two-dimensional plane, as if flying back and forth behind glass in a narrow space. It’s hard to find much information about titles designer James S. Pollak. He has credits on just one other film, The Wheeler Dealers (released, like The Birds, in 1963), though he apparently did uncredited work on the Grand Prix titles a few years later. Is he the same James S. Pollak who wrote the 1946 novel The Golden Egg, a satire of Hollywood? Maybe. Pollak would have been 37 at the time. He could have been a journeyman figure who wandered into creating titles for a few years then wandered out. Whichever the case, this a haunting and strange way to start the movie, made all the more unsettling by the cyan text and titles that fall together in pieces then fall apart just as quickly. In some ways, that process is just as apt a way to open this movie as the birds themselves.

3. What kind of film are we watching?

In the short Blu-ray documentary “Hitchcock’s Monster Movie,” horror scholar David J. Skal posits that, while not a monster movie itself, The Birds would not exist were it not for the giant monster movies of the 1950s. The formula, codified by films like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, Them!, Godzilla and others, involved beasts running amok and threatening civilization, usually as a result of science pushing nature too far. But is that really what’s going on here? Nature pushing back is posited as one explanation for the bird attacks, but not necessarily the most plausible reason in a film that never explains or resolves its central mystery. (More on that in a bit.) It’s another quote, this one in the feature-length doc All About the Birds, that unlocked something for me. Screenwriter Evan Hunter (probably now best known for the crime fiction he wrote under the name “Ed McBain”) claims he came on board after being told Hitchcock would be throwing out “everything but the title” of the Daphne du Maurier novella The Birds adapts and suggested beginning the film like a screwball comedy. *

I’d never thought about it this way, but of course this is what’s going on in the film’s long lead-up to the first bird attack, a gull plunging at Hedren’s skull as she makes her way across Bodega Bay by boat. Hedren plays Melanie, the spoiled daughter of the publisher of a San Francisco newspaper. She has a meet-cute with Mitch (Taylor) in a pet store after Mitch recognizes her then plays along as she pretends to be an employee of the store, a mild example of the pranks that made her a semi-notorious figure. They bicker when she realizes he’s having her on and plots a kind of revenge by delivering the pair of lovebirds he was attempting to buy for his much younger sister Cathy (Veronica Cartwright). When told Mitch has left to spend the weekend at his family home in Bodega Bay, she follows him there.

It’s all classic screwball material. Melanie’s fur coat marks her as a high society outsider in the salt-of-the-earth community of Bodega Bay. She banters with Annie (Susanne Pleshette), a rival for Mitch’s affections. Yet it feels increasingly unsettling the longer it plays out. On page, it’s light comedy, but Hitchcock directs like, well, an Alfred Hitchcock film. When Melanie sneaks into Mitch’s family home while he’s out, everything about the scene suggests something horrible is about to happen. Then, when something horrible finally does happen, everything screwball goes out the window.

It’s incredibly spooky for reasons that are hard to pin down, a daring exercise in not giving the audience what they expect and repackaging the familiar in the form of the “wrong” genre. And yet, neither Hitchcock nor Hunter seems to have seen it this way. “Like all pictures of this nature, its personality didn't carry,” Hitchcock told Cinefantastique in a making-of article published in 1980. "If the picture [he always said ‘picture,’ never ‘film’] seems less powerful today than it did in 1963, that's the main reason, that the personal story was weak. But don't tell that to Evan Hunter.”

He went on to call Hunter not “the ideal screenwriter,” prompting a defensive response from Hunter in the same article (in which he also laments the presence of scenes written by an unknown hand):

“If there were weaknesses in my screenplay […] they should have been pointed out to me before shooting began, and they would have been corrected. I feel the weaknesses were manifold, but only some of them were in the script. The concept of the film was to turn a light love story into a story of blind, unreasoning hatred. Since Hedren and Taylor could not handle the comedy at the top of the film, the audience became bored. They had come to see birds attacking people, so what was all this nonsense with these two people, one who can't act and the other who's so full of machismo you expect him to have a steer thrown over his shoulder? Bad acting and — for Hitchcock — incredibly bad directing.”

The film, however, suggests both were wrong. Something about what we see feels off even before the birds begin attacking. When they do, it plays less like a shock than a confirmation that something is terribly wrong with what we’re watching.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Reveal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.